'I did stunts for my own pleasure': The terrifying feats of French film legend Jean-Paul Belmondo

Alamy

AlamyDecades before Tom Cruise was making audiences gasp, the Gallic star was getting up to even more hair-raising exploits on screen – sometimes with few safety measures.

One of modern Hollywood's great leading men, Tom Cruise, is to receive a fellowship from the British Film Institute this May, alongside a season celebrating his career. Cruise is described by the institution as a "daredevil action star", and someone with a "dedication to reinventing the cinema spectacle" – traits exemplified most of all by his role in the Mission: Impossible series, the latest of which, Christopher McQuarrie's Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, is out this month. However, while it's difficult to think a star of similar stature who performs such awe-inspiring stunts today, Cruise has a forebear who is just as daring, if not more so. That star is Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Alamy

AlamyBelmondo, or Bébel as he is sometimes known, is familiar to many as a figure of 1960s French New Wave cinema. Though beginning his career in the early 1950s with work at Paris's Théâtre de l'Atelier, he soon began acting in films. Nouvelle Vague classics such as Jean-Luc Godard's Pierrot le Fou (1966), Une Femme est une Femme (1961) and Breathless (1960) showed Belmondo working with ease in arthouse cinema, reflecting his intellectual background: his father was a sculptor and his mother an artist. However, Belmondo had an incredibly wide range.

In the same period as he was acting in Godard's avant-garde films, Belmondo worked on many different kinds of film, from French noirs such as Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Doulos (1962) and Claude Sautet's Classe tous risques (1960), to straight dramas such as Melville's Léon Morin, Priest (1961) and, most importantly, Un Singe en Hiver (1962) by Henri Verneuil. As the years went by, it would be Verneuil who would shape Belmondo's later career thanks to his underrated thriller Peur sur la ville (1975). The film turned the actor into a proto-Cruise figure whose physical prowess and fearless stunt work would ultimately define him for French audiences.

His action movie initiation

Celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, and known in English-language territories as both Fear Over the City and The Night Caller, Verneuil's film is relatively simple in terms of narrative. Belmondo plays Letellier, a Parisian police commissaire who, much like Clint Eastwood in Don Siegel's Dirty Harry (1971), doesn't play by the rules. He's haunted by a fatal incident in which criminal Marcucci (Giovanni Cianfriglia) managed to escape after a bank heist. However, Letellier and his sidekick Moissac (Charles Denner) are faced with another problem: a serial killer stalking and murdering women across Paris. It doesn't take long for the two cases to become intertwined as Letellier relentlessly pursues both villains across the city, with much derring-do and many gobsmacking stunts along the way.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPeur sur la ville was not well-received by the critics at the time, who were unhappy with Verneuil following American trends in depicting cops as cowboy-ish gunslingers breaking the rules to clean up cities. "Through some odd work with the trans-Atlantic scissors," wrote Richard Eder of The New York Times, "the Franco-Italian production Night Caller by Henri Verneuil seems to be two completely different movies, neither of them up to much." Eder did say that Belmondo's stunts were entertaining, though; generally, this was the only aspect that was reviewed positively. Equally, French film criticism pulled no punches. Film magazine Positif suggested that the film "evoked the worst of American police films", in particular in its "total absence of social background". What it did have in abundance, however, was Belmondo acting as if he had a death wish. And audiences loved it.

His shift from arthouse darling to action star was considered unusual at the time by some – though it wasn't quite as stark as it appeared. "When I was young, I did stunts for my own pleasure," Belmondo once admitted. "When I was at the conservatoire, I hung from the balconies. I always had a taste for stunts." Professor Lucy Bolton, a senior lecturer in film studies at Queen Mary University of London, says Belmondo's desire for physical roles made sense, given his background. "He was very physical, very sporty, and had a short career as an amateur boxer," she tells the BBC. "Apparently, he stopped because he didn't like his face getting so rearranged!"

Muriel Zagha, critic and co-host of French culture podcast Garlic & Pearls, agrees that there were seeds of Belmondo the daredevil in his earlier career. "Of course, Belmondo was criticised for that shift," she tells the BBC, "which must have seemed to some incomprehensible. But, in hindsight, I see continuity between those two phases of his career. Belmondo said in interviews that there was no difference between the 'pinch' (pincement) of apprehension he felt before doing a stunt and the stage fright he felt before walking on stage. And they were both feelings he enjoyed." Peur sur la ville very much embodies the former pinch rather than the latter.

In spite of the criticism, Verneuil's film was a huge success. Released on Belmondo's 42nd birthday, the film stayed at the top of the French box office for two months, only falling to Ken Russell's rock opera collaboration with The Who, Tommy (1975). It was the second-most popular film in France that year, too, just trumped by John Guillermin's equally stunt-filled The Towering Inferno (1974). Clearly, the public did not share the critics' dismissiveness, and Belmondo's stunts played a huge role in the film's word-of-mouth spread.

Truly authentic action

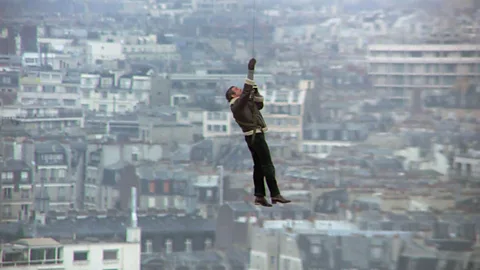

For Peur sur la ville's power as a film lies not so much in the drama of its narrative as it does in the authenticity of its action. As Belmondo said in an interview about the film at the time, "I'm sure that when I do a stunt for Henri, I'll be very well filmed. People will see it's the actor doing it and it would ruin it if you couldn't see that." Initially, the film lulls the viewer into thinking that it may be another straightforward procedural, but it isn't long before the action cranks up a notch, and the actor is climbing precariously over the balcony of a flat. Zoom in on the sequence, and you can see how limited the safety measures were. Behind-the-scenes shots taken during filming by photographer Michel Ginfray show one rope attached to Belmondo, but even this is visible only in the shots where he is climbing over the balcony; his initial approach to it, sidling along a ledge, seems to be done without any precautions.

Alamy

AlamyPeur sur la ville is a film haunted by heights, right from its opening montage of Paris's growing business quarter. Building on some of the trends unfolding in American cinema of the period, in particular the sense of being surveyed from the new, modern towers of glass and steel in films such as Dirty Harry and Alan J Pakula's Klute (1971), Verneuil fills his screen with vertigo-including shots. However, as the film progresses, the key reason for this focus on high-rises becomes apparent: they're really a dangerous obstacle course for Belmondo's Harry Callahan-esque Letellier to tackle. As his character says to a witness early on, "You must see a lot of action in these towers…" It's a forecast for the rest of the film, especially its finale in which Belmondo is lowered from a helicopter down to a high-rise window in order to break in.

The film's most memorable stunts, however, take place in a surreal chase which brings the two central storylines together. The first half of the sequence is a tense sprint across the rooftops of Paris near Opéra and Galeries Lafayette, in which Letellier hunts the film's main killer after he has claimed another victim. But this chase merges with the hunt for Marcucci after he is spotted driving in another part of the city by one of Letellier's colleagues, leading Letellier to embark on a death-defying race through the Parisian Métro in pursuit of the robber.

The first half of this 15-minute sequence alone would be a set piece worthy of any action film. Belmondo has a tendency to run with startling gusto towards the very edge of roofs, sometimes stopping to look down, other times jumping the gap to an adjacent ledge. It was in this part of the chase that the actor genuinely hurt himself, scarring his hand badly after the character misses his jump between the tiled roofs, grabbing a metal gutter à la James Stewart in Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo (1957). The height in this instance is an illusion, with the camera angle hiding a small balcony causeway beneath this particular gap. Still, Belmondo's hand was seriously cut by the gutter. Later, he crashes through the windows of a flat, the falling fake glass also cutting the actor. However, the real death-defying moments take place outside.

Alamy

AlamyIn one scene, where Letellier loses control of his stepping under gunfire, he slides down a sloping roof. In this brief shot, a safety rope can just be seen around his waist. But rather than taking the viewer out of the drama, it's more likely to shock them as they think, "Is that it?!" It seems a paltry safety precaution, and does little to assure the viewer that the actor is really safe, especially as bits of tile come away chaotically with him each time he tries and fails to climb back up.

If this wasn't enough, the second half of the sequence involves a different kind of danger. Clearly taking cues from William Friedkin's The French Connection (1971) and its own chase scene across New York, Verneuil shoots a pursuit around Paris' Métro system. Unlike Friedkin's scene, in which Gene Hackman's Popeye Doyle is behind a wheel, first following a car, then a train, Verneuil's chase is conducted on foot. As Letellier closes in on Marcucci, he takes ever more risks, to the point where he jumps onto the back of a moving Métro train as it leaves the station, and from there proceeds to climb onto its roof. While several sequences of this scene are evidently filmed in the studio with a projected backdrop, several others are very much real, filmed when the train was travelling at around 35mph (55kmh). Belmondo runs along each carriage rooftop before jumping down flat to avoid the coming tunnels, and then carefully walks across the train roof as it trundles over the Pont de Bir-Hakeim. It's utterly hair-raising. As Eder wrote for The New York Times, "Perhaps it is an advertisement for the new high-speed Paris subways."

The man behind the stunts

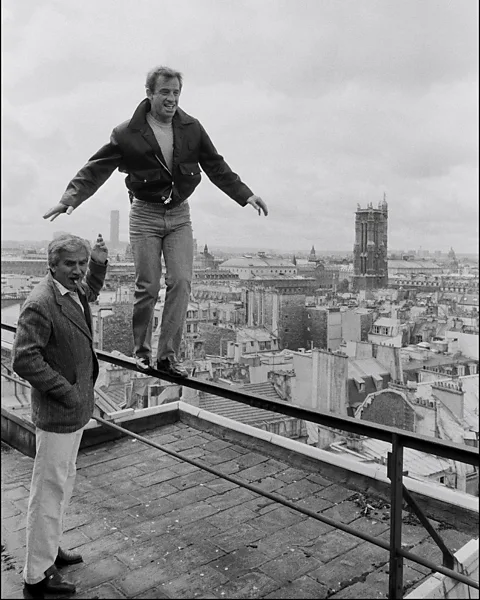

Just to add to the apparent danger, Belmondo is jumping and scampering around rooftops and trains in less-than-suitable 1970s attire: a wide-lapelled blazer and flared trousers, patent leather penny loafers, and a Rolex Daytona 6263 so valuable that, in 2013, it was sold by his F1 driver son Paul Belmondo at Christie's for €165,000 (£140,000). However, Belmondo was more than prepared for the challenges of the film, having been put through his paces by one of the industry's top stuntman, Rémy Julienne.

Julienne had been in the stunt world for some time before Peur sur la ville. He was a specialist in vehicle stunts more than anything else, having been a professional motocross rider. He was Michael Caine's stunt double in Peter Collins' The Italian Job (1969), as he went on to do an array of stunts for the James Bond franchise, starting with John Glen's For Your Eyes Only (1981) and its car chase involving Roger Moore's iconic, disintegrating yellow Citroën 2CV. "I always like to have an accelerator," Julienne once told a French TV show, "and always brush against the limits". Julienne worked prolifically throughout the 1970s in French and Italian crime and action cinema as well, and this is when he first met Verneuil and Belmondo.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 1971, Julienne worked with Belmondo and Verneuil on Le casse (The Burglars), which also starred Omar Sharif. It was a testing ground for Belmondo's daring, with several equally gobsmacking stunts including an incredibly aggressive car chase around the cramped streets of Athens and a remarkable stunt in which Belmondo is rolled out of a lorry's tipper down a steep cliff edge followed by an avalanche of debris. It was the beginning of a fruitful working relationship, with Belmondo and Julienne collaborating on 14 other films.

Belmondo's technical skill with stunts and his propensity for danger feel more than a little proto-Cruise. At the same time, it's impossible to imagine Cruise agreeing to work under such risky conditions, even if modern health and safety measures allowed him to, a factor which makes Belmondo's stunts even more thrilling. But Cruise is undeniably his closest successor. "[Belmondo had a] Cruise level of stunt bravery," says Bolton. "He loved police procedurals, action movies and comedies as much as prestige productions, and seemed untrammelled by any expectations or demands. He was, however, resolutely French, always resisting advances from Hollywood, and so his influence is more national than international."

Verneuil directed only two films with Belmondo after Peur sur la ville , but the spirit of their collaboration lived on in an array of French action policiers. Films such as Georges Lautner's The Professional (1981), and Jacques Deray's Le Marginal (1983) and The Loner (1987), further cemented his position in French popular culture. "He is forever the insolent young criminal from Breathless," Bolton concludes, "but he definitely came to be one of the biggest, most versatile and enduring stars of French cinema." The relationship that really mattered was Belmondo and Julienne's; the stunts they conjured up together defined Bébel's career.

Celebrating their collaboration now feels especially apt considering the Academy's recent accepting of stunt work as a creative part of cinema, via its decision to create a new Oscars category starting next year. Julienne and Belmondo would have almost certainly won such an award, had stunt work been acknowledged as an artform in their day.

Paramount

ParamountWhile Belmondo is remembered in some circles today for his arthouse cinema, ultimately it is his daredevilry that cemented him as a cultural institution in France. "My sense is that his Nouvelle Vague incarnation is one for cinephiles in France," says Zagha, "but that for the majority of French people he was – and remains in the collective memory – a huge star of action films. Those are what made him a monument, a national treasure."

The post-Peur sur la ville career of this national treasure is best summarised by the film's final exchange. "Bravo! What you did was marvellous!" enthuses Letellier's chief (Jean Martin) after the cop has been lowered from a helicopter, smashed into the window of a high-rise block and defeated the serial killer by repeatedly ramming him against a table. "Nah," he quips back. "No brains, all muscle." Belmondo undeniably had both and was one of the most adept actors of his era. But his versatility is rightly remembered as a physical one in the minds of a whole generation of viewers, and his stunts have the power to leave us breathless to this day.

--

If you liked this story sign up for The Essential List newsletter, a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.