'People are still haunted by what happened': How history's brutal witch trials still resonate now

Alamy

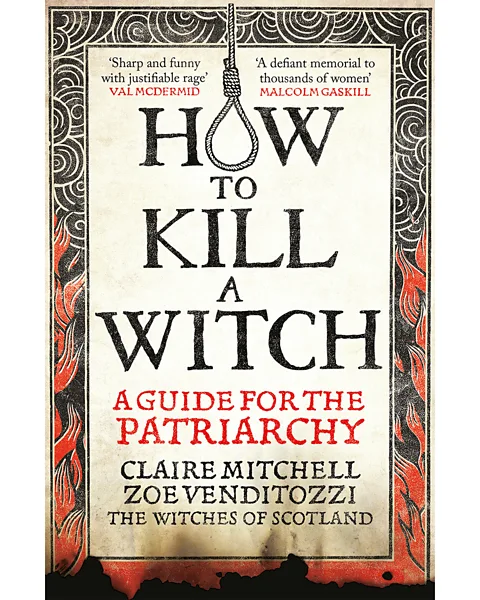

AlamyA new book How to Kill a Witch brings a dark period of history back to grisly life – and an official tartan is being released to memorialise some of those who were tortured and killed.

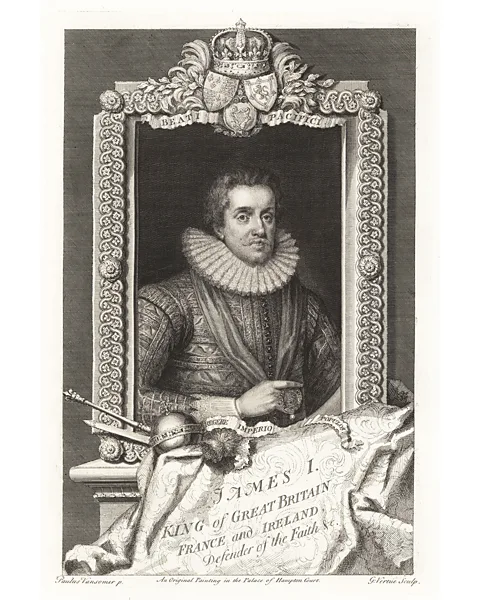

When King James was returning by sea to Scotland with his new wife Anne of Denmark, the voyage was plagued by bad weather – not unusual, for the famously choppy North Sea. But the king was convinced that the devil and his agents – the witches – had a hand in the storm. It was this belief of the king's that sparked the 1563 Scottish Witchcraft Act, and subsequent witch hunts.

This article contains violent details some readers may find upsetting.

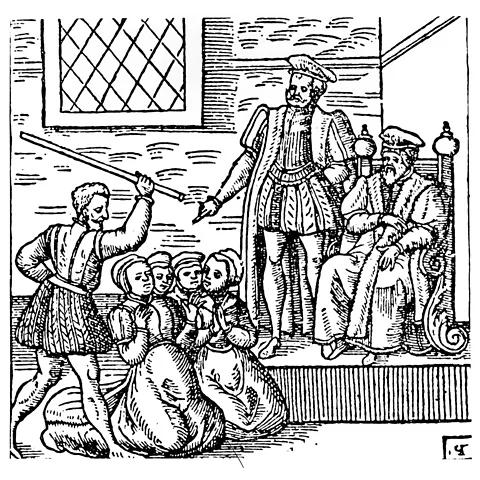

From the 1560s to the 1700s, witch-hunts ripped through Scotland, with at least 4,000 accused, and the executions of thousands of people. Along the way there was unspeakable torture, involving "pilliwinks" (thumbscrews), leg-crushing boots and the "witches' bridle", among other vicious and brutal methods.

Alamy

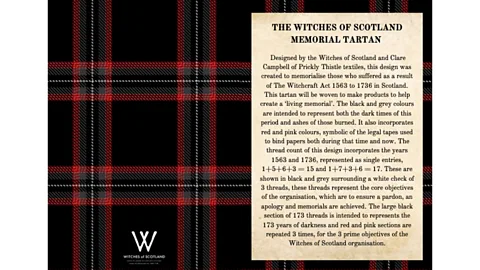

AlamyIn Norway and the US – where witch hunts and trials of a similar scale took place during the same period – those who were executed have been memorialised. Now, in Scotland a new official tartan – which will be incorporated into kilts and other garments – has been released to honour the victims of the Witchcraft Act.

Meanwhile, all things aesthetically "witchy" have been gaining popularity around the world and across generations for several years – WitchTok gains increasing followers and hashtags; the WitchCore look is still attracting fans; witch romance fiction is a growing branch of the romantasy genre. In film and TV Practical Magic 2 is in production for release next year, and TV witch drama Domino Day has been a hit. All of which reflects the fact that neopagans and modern witches are actually on the rise. A modern witch may incorporate nature worship, tarot, magic and rituals with herbs and crystals into their spiritual practise. Involvement ranges from self-care and empowerment to participation in religious groups like Wicca.

The pattern of the Witches of Scotland tartan is a "living memorial" full of symbolism, according to the Scottish Register of Tartans – "the black and grey represent the dark times of this period and the ashes of those burned, the red represents the victims' blood, and the pink symbolises the legal tapes used to bind papers both during that time and now".

The Witches of Scotland/ Clare Campbell

The Witches of Scotland/ Clare CampbellIt's the result of a five-year-long campaign by activists and founders of the Witches of Scotland podcast Zoe Venditozzi and Claire Mitchell, who have now authored a book How to Kill a Witch: A Guide for the Patriarchy, an account of the Scottish witch trials – out this week in the UK, and in the autumn in the US. The book outlines how, as Venditozzi tells the BBC, "the belief system and social anxiety of the time created a perfect storm to find scapegoats and deal with them harshly".

In 2022 the pair achieved one of their goals when Scotland's then first minister Nicola Sturgeon issued a formal apology to the Scots who were persecuted under the law in a "colossal injustice". Some female Ministers in the Church of Scotland have since also issued an apology.

The subject of the witch trials is currently piquing the imaginations of fiction writers too. Hex by Jenni Fagan tells the tale of "one of the most turbulent moments in Scotland's history: the North Berwick Witch Trials". The novel Bright I Burn by Molly Aitken is a fictionalised account of the first woman in Ireland accused of being a witch. And recent historical thriller The Wicked of the Earth by AD Bergin is based around the witch trials in Newcastle, England.

In How to Kill a Witch, the authors show how that moment on King James's voyage was the point from which the story unfurled. "James VI and I [he was the sixth King James of Scotland and the first of England] had a huge impact on the witch trials," explains co-author Mitchell, who is also a practicing KC (barrister) specialising in criminal law and human rights. Among "evidence" were accounts of supposed witches surfing the sea in sieves and dancing in North Berwick Church.

"A few years later James wrote the book Daemonology – a 'how to' guide to find and deal with witches and other spirits". The book was widely disseminated – and his message spread rapidly. The Witchcraft Act was designed to enforce "godliness" in the newly Protestant Scotland, with the law condemning anyone who appeared to be "conspiring with the devil".

Getty Images

Getty Images"People are still haunted by what happened," says historian Judith Langlands-Scott, who has noticed a huge surge of interest in the witch trials in recent years. "King James was obsessed with the bible and believed he was God's representative – and he was obsessed with the idea that the witches were multiplying. Historians widely agree that following the death of his mother [Mary, Queen of Scots] he was brought up to think that women were feeble and easily manipulated because of their carnal desires."

"In Forfar [in Angus, northern Scotland] where I come from, we've learnt that the people who were accused – most of them women – were usually older, disabled or blind people, or people with alcohol addiction. They were people who would have cost society money, who were living on the margins, and were poor and not contributing anything. The community – led by the Presbyterian Ministry – wanted to get rid of them."

"The 'witch pricker' or 'brodder' – who had a financial incentive – proclaimed himself an expert at identifying witches," she says. The most prominent witch pricker of the mid-17th-Century was John Kincaid, who was known as a supposed identifier of "witch's marks" and was involved in the torture and execution of hundreds of accused women. "The accused were stripped naked and examined in front of an all-male congregation [to locate the 'marks' made by the devil] and often shaven all over their bodies."

In Langlands-Scott's view, this demeaning ritual was "very psychosexual, and in Scottish Presbyterian society at the time, sex was a preoccupation". There were witch trials in England but, Langlands-Scott points out that "Ireland and Wales only had one trial each as they believed in the fairies, whereas in Scotland [their belief] was in the devil, and whoever does the devil's work" – ie. witches.

Octopus Books

Octopus BooksFor all the harrowing details in How to Kill a Witch, there are also moments of dark humour. "We've always taken a very serious approach to the facts and horrors of the witch trials, but we definitely have wry, dark humour to cope with some of the more distressing or aggravating aspects of the times," says Venditozzi. "It was always going to be a book that conveyed our personalities rather than being a dry, historical tome. To survive being a woman sometimes means being able to see the humour in terrible situations." The pomposity of the self-appointed witch hunters – with their bizarre methods and feverish imaginations – is laid bare.

The whole system was, after all, elaborate and outlandish. As Venditozzi puts it: "It's a clever trick isn't it, the way in which society blamed women – because they were considered so weak, the devil got to them and got into their knickers, and their confessions about this were often fairly elaborate. All to justify what they were doing. It's bananas!" The authors are not alone in seeing the darkly humorous side – recent comedy TV series The Witchfinder tapped into the ridiculousness of witch-hunting with gallows humour.

More like this:

The book also debunks some misconceptions about the era, including the practise of "burning at the stake", says Venditozzi. "It's a caricature. They did get burnt but they were generally strangled first, then thrown on the pyre to get rid of the body, so the devil couldn't re-animate them, and so that they couldn't get to heaven." This was an extra layer of cruelty, says Langlands-Scott: "to burn the bodies so they couldn’t rise on judgement day, [so] all hope of being put out of their misery would have been obliterated – as the accused would have known going to their death."

Groundswell of interest

The authors acknowledge that there has been a surge of interest in the witch trials – their podcast attracts millions of listeners from all over the world. What has the reaction to their campaign been from the modern witches of today? "We have a great deal of support and interest from modern day witches," says Venditozzi. "The key issue is that we support anyone to practise their beliefs, but that people need to understand that the 'witches' of the period were not being controlled by the devil and were, in fact, just normal people caught up in extreme times. Modern day witches empathise with the plight of the accused as they themselves are sometimes isolated and discriminated against. However, modern day witches are not the same as those accused during the Scottish witch trials."

Alamy

AlamyAs the "WitchCore" aesthetic becomes increasingly popular and commodified, are we are in danger of romanticising the brutal torture and torment of innocent people in history? "No," says Mitchell. "The modern-day witchcraft or WitchTok is very different from the crime of witchcraft hundreds of years ago. People who identify themselves as witches in the present day are not suggesting that they are 'agents of the devil' who are doing evil in society. The modern idea of a witch is far removed from the historical definition."

Langlands-Scott, puts it another way: "People are perfectly entitled to do as they like, and modern-day witches don't try to claim these people who were executed hundreds of years ago as their own. The accused were Christians – though considered heathens and heretics, most of them in the Forfar trials of 1662 [in which 42 local people were imprisoned and tortured] were Catholics. The Presbyterian Church wanted a clean, godly society after [Oliver] Cromwell left Scotland in 1651. They were ordinary people, some of whom might have practiced some folk magic but they didn't commit crimes."

Author Margaret Atwood famously said that the Salem witch trials are an event that replays itself through history – when cultures come under stress. Does Venditozzi agree? "Definitely – when Atwood wrote The Handmaid's Tale, she said that all of the things in it had actually happened in Western culture, and that was in the 1980s. It was very prescient. The wheel turns but there's not much change." In How to Kill a Witch a present-day pastor in the US is quoted warning of witches in his congregation. There is also a section about Advocacy for Alleged Witches an organisation that is "urging compassion, reason, and science to save lives of those affected by superstition".

The Witches of Scotland tartan has been created in order to raise awareness and understanding, says Mitchell. "It's very important to remember our history and learn lessons from it: Scotland fares very poorly in comparison to other countries who have all memorialised those who were accused as witches."

Disney/ Steve Wilkie

Disney/ Steve WilkieSo what lessons can we learn today from the history of the witch trials? "Not to scapegoat vulnerable or isolated members of the community in order to shore up public confidence and security," says Venditozzi. "Despite the fact the witch trials were hundreds of years ago, we frequently see waves of blame against marginalised groups in times of social worry. Claire and I are very optimistic people."

Langlands Scott is also optimistic. "The fact that there is a groundswell of interest to have the truth brought out – and that apologies have been made – is cause for optimism. It's mainly women who are apologising, and I think that's reclaiming the fact that it was mostly women who were tortured and tried. It's almost like giving their voice back, us women giving them a voice, and warning for the present day of what can happen."

How to Kill a Witch: A Guide for the Patriarchy by Claire Mitchell and Zoe Venditozzi (Octopus) is available now in the UK, and will be published in the US this autumn, titled How to Kill a Witch: The Patriarchy's Guide to Silencing Women.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.