Can you solve these time puzzles from the ancient world?

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/BBCAs the clocks go forward this spring, see if you can solve these puzzles based on ancient calendars.

When the clocks change for Daylight Saving Time, it can often involve a bit more mental arithmetic than usual as we try to figure out our schedules. This is especially true for those of us trying to navigate different time zones.

For most of the US, the clocks go forward one hour on the second Sunday in March – unless you're in Arizona and Hawaii, which do not observe Daylight Saving Time. Spare a thought for the Navajo Nation living in Arizona – they move to daylight savings time even though the rest of the state stays on standard time.

And for those making transatlantic calls, the time difference is a little shorter for the next three weeks as the UK and the rest of Europe do not move to their summer time schedule until later in March. But even here there can be mental agility needed - the clocks at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, are a frequent cause of confusion for visitors as they remain on GMT throughout the summer.

In the ancient world, there were far more radical changes to the way people observed and formalised time. The changes to the calendars used by the Romans, for instance, led to seemingly impossible conundrums.

To help limber up your brain for the weeks ahead, we've put together the following time-based riddles with the advice of Helen Parish, professor of history at the University of Reading in the UK. Scroll to the bottom of the article for the answers – or if you'd like a clue, get some hints in this story first.

Puzzle 1: The impossible letter

A woman sits down to write a letter in France on 8 November 1582.

Three days earlier, the letter is received in England.

What happened?

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC

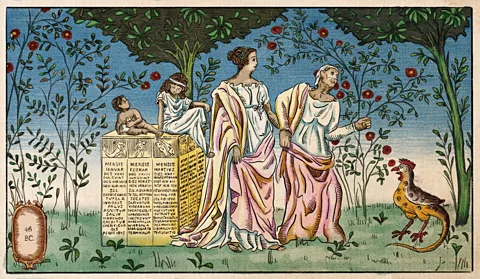

Emmanuel Lafont/BBCPuzzle 2: The mystery of the missing birthdays

In the year 46BC, in Rome, a child is born in spring.

She lives to be 60 years old, though she never has another birthday again.

But why?

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/BBCPuzzle 3: The strangely ageing farmhand

After working in the fields on the last day of December 800BC, a farm labourer downs his tools and goes to bed.

On the first day of the new year, when he picks up his tools to start work again, he is two months older.

How can this be?

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/BBCAnswers

The impossible letter – Puzzle 1

In the 1500s, the old Julian calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar. But different countries in Europe adopted the new calendar at different times – which meant the days across the continent were often out of sync, leaving some countries several days or weeks behind others.

The mystery of the missing birthdays – Puzzle 2

Romans used to use extra months known as "intercalary months", which were added ad hoc to realign the 355-day Roman year with the solar year. The child in question was born in the intercalary month of Mercedonius. The last time the month of Mercedonius was used was spring 46BC, so the child was severely short-changed on birthdays.

The strangely ageing farmhand – Puzzle 3

The pre-Julian calendar only had 10 months, and didn't calendarise the roughly 60 days of wintertime when there was no agricultural work to be done. During this wintertime, there was no real concept of "months".

Bonus:

Even in our modern world there are calendar quirks that mean some people live in multiple time zones where they can be several different ages at once. With a bit of border-hopping, it is also possible to travel back to the 1300s or forward to the 26th Century. Read more in this fascinating feature about the people living in multiple time zones by Erin Craig.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.