Spaghetti science: What pasta reveals about the Universe

BBC/ Getty Images/ Beatrice Britton

BBC/ Getty Images/ Beatrice BrittonWhen you see pasta, your brain probably doesn't jump to the secrets of the Universe. But for almost a century, physicists have puzzled over spaghetti's counterintuitive properties.

You might think physicists only ask the big questions. We mostly hear about the physics of the cosmic and the miniscule, the shape of our universe and the nature of the particles that fill it. But physicists, of course, have ordinary lives outside of the laboratory, and sometimes their way of questioning the Universe spills over to their daily habits. There's one everyday item that seems to especially obsess them: spaghetti.

Going back at least a century, spaghetti has been the subject of rigorous studies. Through this research, physicists continue to learn new things about the solid state of matter, the chemistry of food and even draw connections to the origin of life. The steady torrent of spaghetti science helps to demonstrate that deep questions lurk in our ordinary routines, and that there are plenty of hungry physicists who can't stop asking them.

For example: how thin can spaghetti get? The typical spaghetto – the word for an individual strand of spaghetti – is between one and two mm thick (0.04-0.08in). But other long noodles vary widely in diameter, from udon at 4mm (0.16in) to angel hair at 0.8mm (0.03in). The thinnest handmade strands are called su filindeu, coming in at 0.4mm (0.02in), so slender that only a few women in Nuoro, Italy know how to make them.

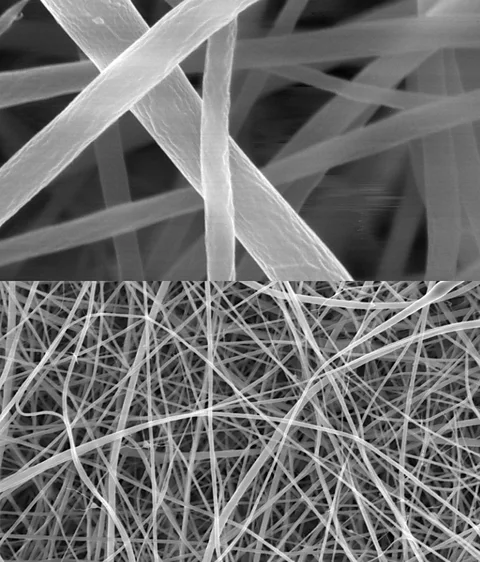

But recently, a team of researchers at the University College London wondered if 21st Century lab equipment could do better. They used a technique called "electro-spinning". First, they dissolved flour into a special, electrically charged solution in a syringe. Then they held the syringe over a special, negatively-charged plate. "This pulls the solution through the dispenser needle down towards the collector plate in a very stringy noodle-type shape," says Beatrice Britton, lead author of the study.

When the solution dried, the researchers were left with a crisscrossing thread of incredibly thin spaghetti. "To the naked eye, all you see is a sort of lasagna sheet," Britton says, but a powerful microscope reveals a mat made of strands as thin as 0.1mm (0.004in). These noodles are also much stiffer than regular spaghetti. Britton and her colleagues hope their research can be a step towards biodegradable alternatives to plastic "nanofibres", which are now used to filter liquids and treat wounds.

A messy science

The world's thinnest spaghetti is just one recent example of how physicists can't seem to stop plying their tools on everybody's favourite carb. But physicists using their noodle on their noodles is no new thing. In 1949, Brown University physicist George F Carrier posed "the spaghetti problem" in The American Mathematical Monthly, which he deemed to be "of considerable popular and academic interest". Essentially, the problem amounts to: "Why can't I slurp up a strand of spaghetti without getting sauce on my face"?

His equations showed how the exposed strand swings about more wildly as it gets shorter and shorter, guaranteeing an eventual slap of the noodle against the slurper's lip – and the fateful sauce eruption Carrier so deplored. Sadly, his mathematical formulas offered no way around the face-slap. It's as deeply etched in the laws of the Universe as the Big Bang.

Beatrice Britton

Beatrice BrittonLater, two scientists inverted Carrier's pioneering study, exploring what happens when a stringy object slips out of a hole instead of being sucked in. They called their version the "reverse spaghetti problem", familiar to any impatient eater who's had to spit out burning pasta because they hadn't waited for it to cool. For now, no theoretical physicist has attempted the more complicated problem of two dogs slurping from either end of the same spaghetti strand.

The great mid-century American physicist Richard Feynman helped unlock the riddles of quantum mechanics, explaining how the elementary particles that make up atoms interact with one another. But Feynman's enormous contribution to spaghetti physics is less widely known. One night, Feynman wondered why it's almost impossible to break a stick of spaghetti into two pieces instead of three. He and a colleague spent the rest of the evening snapping spaghetti sticks until they covered the kitchen floor.

Feynman's interrogation into the counterintuitive physics of dry spaghetti sparked a quarter century of attempts to explain it. This finally happened in 2005, when two French researchers showed that spaghetti always breaks into two pieces – at first. But after the fracture, as the two bent pieces snap straight again, all their pent-up strain gets released in a shockwave, causing further splintering.

In 2018, a team of MIT scientists figured out how to stifle the shockwave – delicately twist the spaghetti strand before snapping it. Their method required lab equipment, but it reliably produced a perfect pair of fragments. Their work provided a new and deeper understanding of brittle rods that goes beyond spaghetti; the phenomenon of three-way fracturing is well-known to pole vaulters, for example.

A mechanical wonder

My (Italian-American) mother taught me to break a bundle of dry spaghetti in half before putting it in boiling water, so it fits horizontally in the pot. I guess Feynman did the same, but it's an outrage to many of the world's spaghetti-eaters. If you're in the latter camp, then you place your dried spaghetti bundle upright in the pot of boiling water, then watch it slowly soften, buckle and submerge itself.

This familiar spaghetti behaviour may not seem like a puzzle, but try removing a recently-curled piece of spaghetti from the pot and letting it dry. It will stay curved rather than returning to its original straight length – something in those first few minutes irreversibly changes the composition of the spaghetti. In 2020, two physicists finally explained this spaghetti transmutation. It's due to a feature called "viscoelasticity" – a name for the unique way materials like spaghetti respond to physical stress. This special property allows water to flow through the strand's outer layers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe strange mechanics of cooked spaghetti go even further. In one study, scientists dropped strands on the ground and measured how they coiled to learn about other elastic materials, from rope to DNA strands. In another, physicists tied spaghetti into knots and studied what types of strain would cause them to tear.

Spaghetti physics even goes beyond the pasta itself – sauce is loaded with its own scientific mysteries. When eight Italian physicists met while doing research abroad in Germany, they found a shared frustration in the classic Roman dish cacio e pepe.

The sauce requires very few ingredients – it's basically a mixture of reserved pasta water and grated pecorino cheese – but they'd all experienced its mystifying fickleness. Often the cheese irreversibly clumps up, ruining the sauce. This is especially common when you cook it in large batches, which made the physicists hesitant to invite their German colleagues to dinner. "We can't mess up cacio e pepe in front of German people," says Ivan Di Terlizzi, who studies statistical and biological physics at the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems in Dresden, Germany.

Fortunately, among them were some of the world's foremost experts on the physics of "phase separation", exactly the kind of congealing phenomenon that plagued their group dinners. Arguing about the phase separation of cacio e pepe, they realised it was flummoxing from a scientific perspective as well.

"This is actually a very interesting problem," says Daniel Maria Busiello, co-author on the cacio study. "So we decided to design an experimental apparatus to actually test all these things."

The "apparatus" consisted of a bath of water heated to a low temperature, a kitchen thermometer, a petri dish and an iPhone camera attached to an empty box. They invited as many hungry friends as they could find to Di Terlizzi's apartment and hunkered down to cook a weekend's worth of cacio e pepe.

They found that the "simple" sauce was enormously complex. Chemically, it's a water-based solution with only a few components: starch (from the pasta water), lipids (from the cheese) and two kinds of protein (also from the cheese). Using their apparatus, they found a physical explanation for the sauce-wrecking clumps, which they termed the "mozzarella phase".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesProteins, unlike most molecules, get stickier when they're hot. As the sauce is heated, the researchers found this leads to these proteins sticking to the lipids and forming mozzarella-like clumps. In a well-made cacio e pepe, what prevents this is the starch, which forms a protective coat around the lipid molecules so they can't stick to the proteins. If the sauce gets too hot, the increased stickiness of the proteins overcomes this barrier.

Once they understood the science behind the sauce, it was clear how to fix it. "If you add enough starch above a certain threshold, you don't get this kind of separated state," says Di Terlizzi. Pasta water doesn't typically contain enough starch to guarantee this threshold, so they suggest adding a mixture of corn starch dissolved in water.

The group decided to conclude their manuscript with a foolproof recipe for the classic dish. But in surveying the rich scientific literature, they realised they weren't the first to reach this cacio epiphany. In the name of academic integrity, they cited a YouTube video wherein the Michelin-star Roman chef Luciano Monosilio suggests the same tweak for a foolproof recipe – a dash of corn starch. "It's the only non-scientific reference in our paper," says Di Terlizzi.

The physics they used connects the clumping of cacio e pepe to ideas about the origin of life on Earth. Biophysicists use phase separation to understand how droplets of liquid can congeal and divide within a solution. "A droplet dividing pretty much looks like a proto-cell," says Giacomo Bartolucci, another co-author on the study. Inside the little blobs that preceded actual cells, some believe, the building blocks of life may have come together via a process much like the Italians’ mozzarella phase. The same ideas are helping biologists understand how the plaques that cause Alzheimer's coalesce in the brain.

Why is spaghetti such a locus of speculation and study for physicists?

For one, it's simple – flour, water and heat, says Vishal Patil, one of the discoverers of the twist-and-break method who is now a professor of mathematics at the University of California, San Diego. The fact that a combination of so few components raises so many deep questions speaks to how physics underlies everything they see and do, Patil says.

It also shows that no matter how deep physicists probe the big and the small, the answers can still fall short of explaining phenomena we see every day. When it comes to cacio e pepe, all the tools of theoretical physics can only tell us what every Italian grandmother knows: keep the stove burning low when you make it. Laboratory electrospinning can only achieve marginally thinner spaghetti than what the women of Nuoro, Italy make daily by hand.

"Spaghetti is just a very accessible thing you can play with," Patil says. The low cost of flour-based noodles is what made them a democratic delicacy for so many cultures around the world – spaghetti was popularised in Naples as street food. That's why Feynman didn't hesitate to snap pounds of the stuff onto his kitchen floor.

After a long day at the blackboard, plugging away at the impenetrable math of quantum mechanics or black holes, the mechanical wonders of spaghetti are the perfect fodder for scientists' mealtime probing.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.