Lost manuscript of Merlin and King Arthur legend read for the first time after centuries hidden inside another book

Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University LibraryAn intriguing sequel to the tale of Merlin has sat unseen within the bindings of an Elizabethan deeds register for nearly 400 years. Researchers have finally been able to reveal it with cutting-edge techniques.

It is the only surviving fragment of a lost medieval manuscript telling the tale of Merlin and the early heroic years of King Arthur's court.

In it, the magician becomes a blind harpist who later vanishes into thin air. He will then reappear as a balding child who issues edicts to King Arthur wearing no underwear.

The shape-shifting Merlin – whose powers apparently stem from being the son of a woman impregnated by the devil – asks to bear Arthur's standard (a flag bearing his coat of arms) on the battlefield. The king agrees – a good decision it turns out – for Merlin is destined to turn up with a handy secret weapon: a magic, fire-breathing dragon.

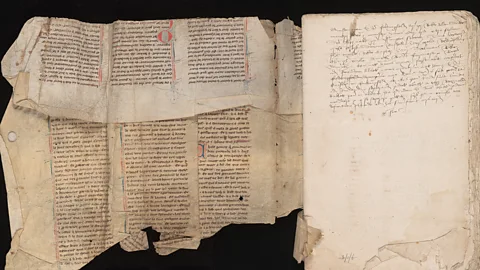

For over 400 years, this fragile remnant of a celebrated medieval story lay undisturbed and unnoticed, repurposed as a book cover by Elizabethans to help protect an archival register of property deeds.

Now, the 700-year-old fragment of Suite Vulgate du Merlin – an Old French manuscript so rare there are less than 40 surviving copies in the world – has been discovered by an archivist in Cambridge University Library, folded and stitched into the binding of the 16th-Century register.

Using groundbreaking new technology, researchers at the library were able to digitally capture the most inaccessible parts of the fragile parchment without unfolding or unstitching it. This preserved the manuscript in situ and avoided irreparable damage – while simultaneously allowing the heavily faded fragment to be virtually unfolded, digitally enhanced and read for the first time in centuries.

Previously, it was catalogued as the story of Gawain. "It wasn't properly inventoried," says Irene Fabry-Tehranchi, the French specialist at the library. "No one had even recorded that it was in French."

Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University LibraryWhen she and her colleagues realised the fragment told a story about Merlin and his ability to change shape "we were really excited," she says.

The Suite Vulgate du Merlin was originally written around 1230, a time when Arthurian romances were particularly popular among noblewomen, although the fragment is from a lost copy dated to around 1300. "We don't know who wrote the text," says Fabry-Tehranchi. "We think it was probably a collaborative exercise."

It is positioned as a sequel to an earlier text, written around 1200, in which Merlin is born a child prodigy gifted with foresight and casts a spell to facilitate the birth of King Arthur, who proves his divine right to rule by pulling the sword from the stone.

"The Suite Vulgate du Merlin tells us about Arthur's early reign, his relationship with the knights of the round table and his heroic fight with the Saxons. It really shows Arthur in a positive light – he's this young hero who marries Guinevere, invents the Round Table and has a good relationship with Merlin, his advisor," says Fabry-Tehranchi.

It is thanks to the sequel, she says, that the story of the Holy Grail – and Merlin's place in that story – could be retold in a coherent way from beginning to end. "If the sequel was written to facilitate that, it was successful. That became the main way the story was transmitted."

Stylistic evidence in the text indicates the fragment was written by an unknown scribe in a northern French dialect understood by English aristocrats. "These are Celtic and English legends, which had circulated orally across the British Isles. But the language used when they are written down is Old French, because of the Norman Conquest."

By the 16th Century, however, Old French had fallen out of favour in England. "There was a linguistic shift to English among readers of Arthurian literature," says Fabry-Tehranchi. This may be why the fragment ended up as the book binding of an archival register: "The text had lost its appeal, so they wanted to reuse it."

Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University LibraryThe library wanted to preserve the register, which was created in 1580 to record the property of Huntingfield Manor in Suffolk, as evidence of 16th-Century archival binding practices in England.

Previously, it would have been necessary to cut this binding to access the parts of the folded fragment, and the heavily faded areas of the texts would have remained illegible.

Today, multispectral imaging (MSI), CT scanning and 3D modelling has enabled scholars to not only read the faded and hidden texts of the fragment, but to understand exactly how it was folded and sewn into the register. The Cultural Heritage Imaging Laboratory team at Cambridge University Library has even been able to analyse the different threads used by the Elizabethan bookbinders and the different decoration pigments used by the medieval illuminator, whose job it was to "illuminate" manuscripts with decorative illustrations and rich colours.

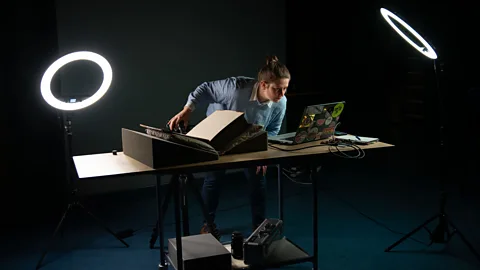

Down in the basement of the library, in a small photographic studio dominated by a multispectral camera that cost over £100,000 ($125,000), the lab's chief photographic technician Amélie Deblauwe says: "The specialist imaging techniques that were employed on the Merlin fragment revealed details that would not be visible to the naked eye."

The camera takes 49 images of each page using different combinations of light panels emitting different wavelengths of light into both sides of the paper. Starting with invisible ultraviolet light, it moves right through the visible spectrum – "all the colours of the rainbow" – to invisible infrared light, she says. "All of these are measured in nanometres. So we very accurately know what we are doing to the page with these lights, we are really in control of what we're bombarding it with."

Using a range of light colour bands meant that even the tiniest residue of ink, which had chemically degraded over time, could be made to stand out clearly in images. Technicians made the writing more legible by processing the image data using geospatial and open source software. "That's because different inks and different papers react differently to different lights," Deblauwe says. While some lights are absorbed by the parchment and the ink, others are deflected, illuminating different details.

The camera can even reveal tiny scratches on the parchment by sending light towards the paper at different angles, creating "surface shadows". "We call it 'raking light'," says Deblauwe.

An unexpected discovery came when the images revealed that the parchment was significantly lighter in the middle. "That was an amazing moment for me," says Deblauwe. "It was a little bit noticeable in the colour image, but it became really apparent in the MSI."

Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University LibraryAfter she saw these images, she realised the parchment was also shinier in the middle and had a waxier feel to it. This indicates that a leather strap had probably once been tied around the middle of the book to hold it together more firmly and, over time, rubbed some of the parchment's fibres away. "Sometimes you have a bit of a lightbulb moment, and that gives you a greater understanding of the history of the item," says Deblauwe. "This is next level study of manuscript material."

One of the "trickiest" challenges the team faced was how to access the text hidden by folds, says Fabry-Tehranchi. The solution was for conservators to carefully handle the parchment while technicians inserted a "very narrow" macro probe lens into the darkest crevices of the hidden areas via any part of the parchment that was still accessible.

"The lens can get very close to an object," says chief photographic technician Błażej Władysław Mikuła. "We take multiple shots, and we stitch the images together."

The result was hundreds of images of Old French words and letters – all handwritten by a medieval scribe – which needed to be put together like a jigsaw. To add a further layer of complexity, some of the images were taken using mirrors to reflect otherwise inaccessible areas of the text, so the images were curved or needed to be rotated or flipped.

Figuring out where a particular image belonged was a painstaking process, but it was ultimately very satisfying, says Fabry-Tehranchi. Only a few square centimetres of the text remain unseen, due to the placement of the thread, but otherwise the fragment has been forced to give up all its secrets.

Using a CT scanner, which can distinguish between different materials, the team was even able to digitally remove the thread from the spine of the book in a new process which allowed the stitches and materials used by the Elizabethan bookbinders to be analysed. "We never knew that we would obtain such a good quality image of the structure of the binding," says Fabry-Tehranchi. "It's amazing."

Mikuła sometimes wonders what these Elizabethans would have made of all his efforts to analyse the fragment. "They saw it as a piece of rubbish. It could never have crossed their minds what we would do to it." He suspects there may be other such manuscripts out there. "This library is full of treasure that needs to be discovered."

* Digitisation, analysis and edition of the medieval French fragment of the story of Merlin re-discovered at Cambridge University Library, a free talk by Irène Fabry-Tehranchi, Amélie Deblauwe and Błażej Władysław Mikuła, will take place at 5pm on 26 March during the Cambridge Festival.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.