How megafloods in California start in Japan

Getty Images

Getty ImagesStorm-hunting planes chase atmospheric rivers through the sky from Japan to the US, revealing new insights into these powerful storms and how we can keep ourselves safe.

It was an early morning in February, and Capt Nate Wordal, a storm-hunting US Air Force pilot, was flying out of Yokota Air Base west of Tokyo. After fighting some turbulence coming off Mount Fuji, he was headed for the vast, blue expanse of the Pacific Ocean. His destination: a type of storm known as an atmospheric river, which was developing off the coast of Japan.

Atmospheric rivers are invisible ribbons of water vapour in the sky. The ones Capt Wordal was hunting form in the Pacific Ocean then travel eastwards to the US West Coast. When they hit the coast and flow up the mountains, the vapour cools, turns into rain or snow and is dumped on the ground – where it can bring devastating floods and avalanches. But the "sky rivers" also bring benefits, and are vital for preventing droughts: in California, they contribute up to 50% of annual rain and snow in just a few days each year. They occur in winter – which for storm-chasing pilots like Capt Wordal, adds another job after the summer hurricane season.

"Our main mission during the year is hurricane hunting," says Capt Wordal, a hurricane hunter with the Air Force 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron. He usually spends the months between May and November flying through hurricanes and dropping weather instruments that capture real-time data for the National Hurricane Center. "And then our next season that we've started in the last few years is this atmospheric river mission," he adds, where the flights gather data on those storms, typically between November and March.

U.S. Air Force

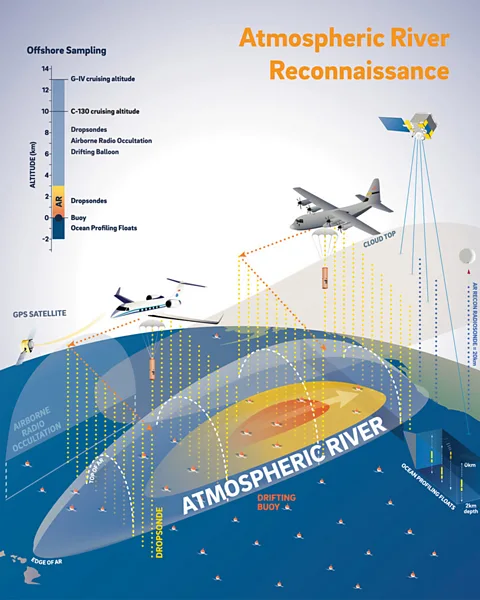

U.S. Air ForceThis year, for the first time, some of the flights started in Japan, in addition to flights out of Hawaii and the US West Coast, to measure the storms early on in their journey and create more accurate forecasts.

Generally speaking, "our weather is moving west to east around the northern hemisphere, so the more accurate information you have about a storm further [west], the more you can understand how it's going to evolve," including how much rain or snow it will bring once it makes landfall, says Anna Wilson, an extreme weather specialist. Wilson is the field research manager for the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego – which is is one of the partners of the mission, along with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa).

The flights, known as the Atmospheric River Reconnaissance campaign (or AR Recon for short), were started almost 10 years ago by Scripps, Noaa and the Air Force. The missions have grown in scope and reach since then, as atmospheric rivers and their impact have been increasingly in the spotlight.

In the western US, atmospheric rivers are the main cause of flood damage, causing more than $1bn (£753m) a year in such damage. They are becoming bigger, and the strongest ones are becoming more frequent, due to climate change, as warmer air holds more moisture. But people's ability to forecast, prepare for, and cope with these storms and the floods they bring, is also advancing – helped by data from the flights.

_ Lavers et al 2024, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 105, 1

_ Lavers et al 2024, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 105, 1"We fly to the [atmospheric river], we cross it multiple times if we can. We really target the [atmospheric river] itself as well as the weather conditions near it that will influence its movements, its growth, its weakening," says Marty Ralph, a meteorologist and the director of the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes at Scripps, as well as the Atmospheric River Reconnaissance programme's principal investigator.

To gather the data, a team in the back of each plane drops cylindrical instruments called dropsondes into the atmospheric river. The dropsondes collect data as they fall through the evolving storm, measuring its temperature, air pressure, wind and moisture, as well as its direction. In addition, the flights out of Japan dropped drifting ocean buoys – each of which is "about the size of a washing machine", says Capt Wordal. They drift in the Pacific Ocean and measure the waves and water temperature, for an ocean observation programme run by Noaa.

"Our data is changing the forecast of where [atmospheric river] is going to hit the coast, when, with what strength and from what angle," Ralph explains. These measurements fill gaps in the data from satellites.

More days to get ready

The information provided by the flights results in more accurate forecasts days before the storm hits, evaluations of their impact suggest. This in turn can help weather services issue appropriate warnings in time, as well as helping reservoir managers decide whether to release water to catch the coming rain and prevent floods.

Until this year, the flights measured atmospheric rivers and fed the information into the forecasts up to five days before the storms hit the coast. With the Japan flights, the aim was to extend these accurate, detailed forecasts by a few more days – and give people on the ground even more days to prepare.

"Our goal in going to the western Pacific, is to maybe try and get an eight-day forecast improved, or even, a 10-day forecast," says Ralph. "The further west we can go, the more likely it is we can improve the forecast more than five days out."

He adds that it can be several storms, influencing and sometimes merging with each other: "It's not like it's one single storm moving the whole way." Each atmospheric river can be several hundreds of kilometres wide, and can transport over 20 times as much water as the Mississippi River.

Flying over cyclones

The flights from Japan started on 3 February, and measured a big atmospheric river that formed off Japan, Ralph says, showing a series of maps on a video call. In the days that followed, that atmospheric river then triggered a cyclone northwest of Hawaii, he explains. (Studies suggest that atmospheric rivers can make cyclones more powerful due to the moisture they bring.) A separate flight out of Hawaii measured that cyclone, while others flew over further atmospheric rivers developing off Japan, he says. After about a week of these atmospheric rivers moving east, gathering strength, and another one developing into a cyclone, the storm then made landfall over California on 12 February.

The storm brought heavy rain and floods to coastal California, and deep snow to the Sierra Nevada, leading streams and reservoirs to rise. It forced some evacuations due to the risk of landslides near burn scars from the recent Eaton and Palisades fires in Los Angeles. But it also helped improve drought conditions in Central and Southern California, according to a preliminary analysis – an illustration of benefits alongside the risks of atmospheric rivers.

For the pilots, the mission is in some ways less intense than hurricane hunting, says Capt Wordal – but the long flights required to chase atmospheric rivers, which can last 10 hours or more, present their own challenges, such as fatigue. The missions are flown with the Air Force's Lockheed WC-130J Hurricane Hunter aircraft, and Noaa's Gulfstream IV aircraft.

"The flying is completely different [to hurricane hunting]," says Capt Wordal. To measure a hurricane, he and his crew fly into it, and spend two-to-four hours battling intense conditions: "Some people compare it to driving through a car wash, because you can get just unbelievable amounts of rain," as well as hail, lightning and heavy turbulence, he says.

By comparison, flying through or over a brewing atmospheric river is calm, says Capt Wordal: "We're doing these giant race tracks across the Pacific Ocean, these really long flights, and we're getting the data of this atmospheric river that's going though the sky."

However, as the atmospheric rivers approach the US West Coast, they become more aggressive and the crews can then experience more storm-like, turbulent conditions, Capt Wordal says. This makes returning to base and landing on any coast much more difficult due to the intense winds and rain hitting the airfield, he adds. In his experience, the challenge is to stay fully alert and engaged to support the crew doing the measurements and keep everyone safe.

The pilots – usually two or three – ensure that the plane is where it needs to be, and that there are no ships below. Navigators are a large part of the mission and work very closely with the pilots and weather officers to chart a safe and efficient flight plan, he explains. In the back of the plane, loadmasters load and drop the dropsondes, and weather officers process the real-time data from the dropsonde and send it to Scripps. "And then they're right onto the next dropsonde. They do this for hours upon hours at a time, they have a lot of work to do in the back, they're really on it," he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe next big storm

The impact of the flights out of Japan, and the potential difference they made to the forecasts and situation on the ground, is still being analysed, according to Ralph and Wilson.

"What we expect strongly to see, based on our prior results [and preliminary results from the Japan mission], is seeing additional lead time for impactful events for the US West Coast, just because of having those initial observations upstream, where some of those atmospheric rivers are being generated," says Wilson, who serves as the AR Recon programme's coordinator.

"Getting better and better at targeting the right spots there and then seeing the impact in the forecasts on the US West Coast, is really exciting," she adds.

In 2021, for example, flights out of Hawaii measured several atmospheric rivers and cyclones about five days before they hit California. Without the dropsonde data, the forecast was for a not very concerning storm, but with the data, the forecast changed to a major atmospheric river storm, Ralph says. This in turn helped people get ready: knowing that a big storm was coming, "the emergency preparedness community sprung into action, they closed roads, they evacuated neighbourhoods, in anticipation of a possible serious storm," he says. When the storm did hit, it caused substantial damage, "but there wasn't a loss of any life, so that was a success story in emergency preparedness," he concludes.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPreventing droughts

In addition, such preparedness can be vital for drought prevention, Ralph says. Given that atmospheric rivers are so important for the water supply, reservoir managers face a difficult choice, he explains: if they empty a full reservoir ahead of a predicted big storm with heavy rain, and that rain then turns out to be less than expected, they've lost the next summer's water supply. "If there are no more storms for that winter, they can never get that water back [before the summer]," he says – when it will be needed for farming, for example.

But if reservoir managers have accurate forecasts, thanks to the flights, telling them for example that a big storm is coming in three days, they can confidently release water from the reservoir, knowing how much rain will come, and creating space to catch it. (Read more from the BBC about what the flights have revealed about atmospheric rivers, and how these powerful storms are evolving with climate change.)

With the atmospheric river season now over, Capt Wordal is ready to switch over to his other task: chasing hurricanes.

"End of this month is when the hurricane season starts," he says, speaking in May. "April, May, are somewhat down months, where we get back to our training, and getting everyone ready – before we launch into the tropical storm season."

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.