Covid 2020: An intimate look at health worker's lives amid a global crisis

David Collyer

David CollyerHealth worker David Collyer wanted to shoot a documentary photography project on the last years of the Welsh hospital he worked in. Then Covid-19 appeared.

On 6 May 2020, a strangely atmospheric picture graced the British daily newspaper The Guardian.

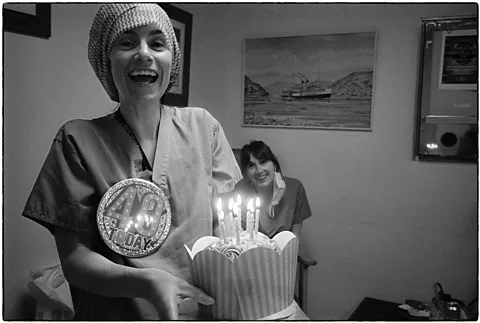

The picture showed a woman in hospital scrubs laughing as she was handed a birthday cake. In the background, another woman could be seen laughing too. The scene seemed to have been lit, mostly, by the flaming candles on top of the cake.

The image, and others alongside it, was unlike most pictures The Guardian usually ran: it was black and white, for starters. The characteristic grain hinted that it had been taken on film instead of a digital sensor. And it was taken not by a professional news photographer, but by a fellow health worker, joining in the birthday celebrations as a brief respite from working on the frontlines of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

David Collyer took this picture in the first few months of 2020, on shift for his job as an operating department practitioner (or surgical nurse) at the Nevill Hall Hospital in Abergavenny in Wales. As the hospital began to be inundated with Covid-19 patients in the first wave of the pandemic, Collyer decided to document what he and his colleagues were witnessing, all captured on a small 35mm film camera.

Documenting the day-to-day experience of the hospital's theatre staff was a project that Collyer had long considered. "The Trust that I worked for had built a big new central hospital which opened during Covid," Collyer says. "I'd already thought about doing this project to sort of document the last couple of years of Nevill Hall. And then, of course, Covid came along.

"That was the catalyst that made me actually get the camera and say, right, we need to do this now. It was a project that was already planned, and it just so happened that Covid turned into the project."

David Collyer

David CollyerCollyer first became aware of the impending pandemic long before the hospital was inundated with patients. "I started seeing the images coming in on the news from Italy, really, that's, that's what was the real eye opener," he says. "We were suddenly aware that something was doing the rounds. And then, of course, you started to get these news stories coming onto the 10 O'Clock News at night."

As government scientists started to warn of Covid-19's arrival in the UK, Nevill Hall's staff started making crisis plans. "Then when we stopped elective procedures, and, you know, we're only doing emergency procedures. And then there was this kind of lull where we didn't really know what was happening," he says. "It was a bit like a tsunami. You know it's coming. You've been told it's coming, and you're standing on the shore, you can kind of hear it, and you can see it… you're looking at the reports around the world, but you don't know when it's going to make landfall.

"The hospital prepared by setting up an Intensive Therapy Unit (ITU) which would offer initial care to suspected Covid cases. Then all of a sudden, the first one [Covid-19 case] came through the door, and then the second one came through the door, and then, you know, one ITU space got turned into two, got turned into three. Every patient that came into theatre had to be treated as if they were Covid-positive." Collyer says this meant the hospital's frontline staff had to wear full personal protective equipment (PPE), as well as ventilating the air every 20 minutes.

For around two months, Collyer took his camera – a tiny 1980s model called the Olympus XA3 – into work for each shift. The camera was small enough to keep on a neck strap under his scrubs when not in use, and its shutter is very quiet. Collyer chose not to use flash, either, giving his images a grainier look.

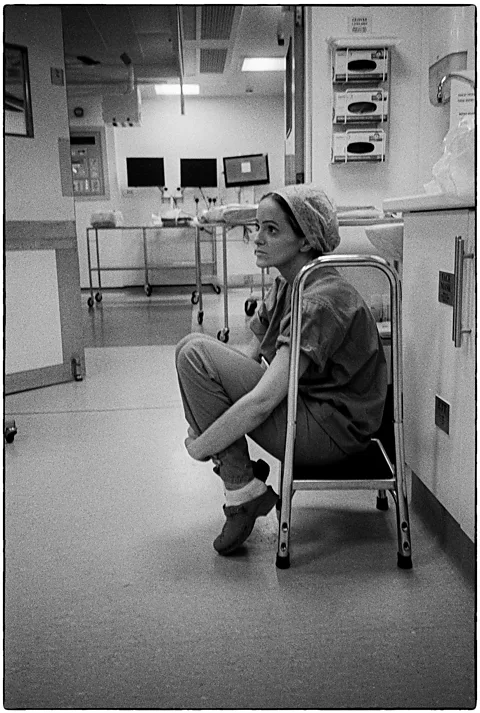

None of his pictures were of the many patients receiving care at Nevill Hall – partly for privacy reasons, but also that was the focus of so much photojournalism being produced across the world. Collyer instead trained his camera on the hospital staff. He captured colleagues snatching a few minutes respite in-between cases, extreme tiredness etched on their faces, or sitting slumped on chairs and wheelchairs in staff rooms after long and hectic shifts. In one picture, a nurse ties back a colleague's hair in a break room; in another, a visibly exhausted health worker sits slumped against the wall, still wearing his PPE and protective visor. They are moments of calm away from the biggest health crisis the world had seen in decades.

"If I'd wandered around with a DSLR, putting it in people's faces, then people act in a very, very different way. I've got something that's smaller than the palm of my hand, and it's literally just click, click, click. It lends a different sort of nuance to the to the body of work," Collyer says.

David Collyer

David CollyerThe Guardian chose to run a photo essay of his work, and it was the image of his colleague's Lauri's shift-time 40th-birthday celebration was included. "She'd chosen to come into work on her 40th birthday, when she could have got it off, to deal with this crisis," Collyer says, adding that NHS teams often bond over shared experience in difficult times. "In order to be able to get through something like Covid, you have to have ways of finding joy in the situation, as well as amongst yourself as a group of people. And to me, that photo really sums that up. Because if you don't have moments like that, then you can't really deal with what you see on a daily basis.

"We all, in the courses of our career, have seen tragic events and people dying, but there was the element of the unknown coming with it as well. And was it going to get us?"

The single location – the interior of Nevill Hall Hospital – also shows the monotony many of the health workers had to contend with. "What [photographer] Peter Dench said about my photos at the time was that they had this feeling of claustrophobia about them… that really resonated about what Covid was like. There was this incredible feeling of claustrophobia, not just because of the PPE that we were wearing, which was a lot more severe than we were used to. Because you were kind of stuck in the hospital a lot of time, you couldn't go home. You had to shower after every case, you know, you had to decontaminate yourself on the way in and out… so it was a pretty tough time.

"On top of this, we were watching people die and, and we were hearing reports coming in from around the country of NHS workers that were dying as well, you know. I've got a friend who's a respiratory professor up in Leeds, and he lost five colleagues," Collyer says.

David Collyer

David Collyer"I wanted to sort of look at how we bonded as a team… because I didn't shoot patients, you almost take Covid out of the picture. It was really looking at how a team worked together under a stressful situation, and that stressful situation happened to be Covid.

More like this:

• Covid 2020: The body in the bed

• Covid 2020: A landmark without a crowd

• Covid-19: What happened to the countries that didn't lock down?

"I always say that to work in theatres, you need to have a strong stomach and a dark sense of humour… you've got to be able to find moments of humour and joy in the darkest moments to do the job. That's really what I wanted to capture. Not just people with thousand-yard stare on, looking absolutely shellshocked, knackered at eight o'clock in the morning. But I wanted to capture those moments of human interaction and warmth that really sort of held us together as a team."

Such was the reception of Collyer's work that his pictures were turned into a book called All in a Day's Work, which raised money for mental health charities. The project earned him the Royal Photographic Society's documentary photographer of the year in 2021. But the photographer's jubilation had to be put on hold: just weeks later he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. (He has since made a full recovery.)

"All of a sudden, I'm the patient in the system, and I'm being shielded in a private hospital as an NHS patient, because that's where all of the cancer cases in South Wales are going to shield them from Covid," he says. Covid-19 was still widespread, and Collyer's cancer prognosis made contracting it potentially much more serious. "I just remember coming home from the operation, and I was sat on the sofa, and I suddenly I started getting the rigors, which is like where your body suddenly starts dramatically shivering, you're spiking a temperature. I was terrified that I was going to have to go back into hospital."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, Xand Instagram.