'There are so many hidden costs to raising a disabled child'

BBC

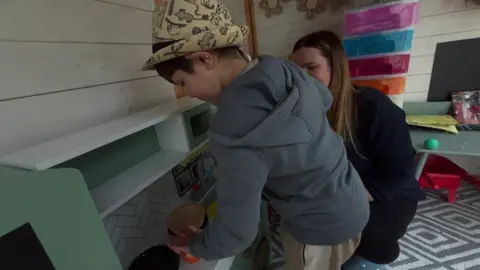

BBC"Our bills are always higher."

For Amanda, a mother of two sons, raising a disabled child comes with hidden costs that have forced her out of the workplace.

Her seven-year-old boy, William, has medical conditions that leave him unable to attend mainstream school and with significant care needs.

She has never been able to return to her job managing an opticians because of the difficulties in finding a specialist childcare provider able to accommodate William.

Amanda, from Skipton in North Yorkshire, told the BBC that her family also faced financial pressure because of the equipment and clothing that William needs.

"I'm not a natural stay-at-home mum, I enjoyed working," she said.

To be able to afford to go back to work, Amanda would have to have childcare and claim it back through Universal Credit, but the carer would need to be Ofsted-registered.

"Finding someone who's registered and willing to look after a child with William's needs is nearby impossible."

Her plight has been highlighted by The Family Fund charity, which has warned that families with children with additional needs are at risk of falling into debt because of care demands.

William has epileptic encephalopathy, a genetic condition that can cause developmental delays, a movement disorder called ataxia and learning disabilities.

When he was first diagnosed, Amanda was told that he may not survive until adulthood.

"He has a high risk of SUDEP (Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy) where some children pass away in their sleep. When your child sleeps in you think 'is this going to be the day that they don't wake up'."

Amanda said there was no "downtime" for parents in her situation and she faced "full-on and long days".

"It's hard to explain because he is such an adorable lively boy, everyone who meets him adores him, but he never stops."

She said the main challenge was William's behaviour.

"If you take him to a body of water, he will want to go in that. If we go to a soft play, he will pull on hair. The isolation is the hardest thing.

"You have no control over anything that happens, you just have to ride the waves and deal with it really."

Her household budget is impacted by William's love of water and by food wastage.

"He has an obsession with water so we use water a lot. Wastage of food is a big one, I want to try and get him eating different things but he is restricted on what he will try."

She said nappies and incontinence swimwear "cost a bomb" as does his clothing, which needs holes for his gastrostomy - a surgical opening in the stomach for a feeding tube.

"When we go out, we seem to pay more for specialist stuff, £50 or more for an hour so they can have fun and be by themselves or with children with additional needs."

William has a place at a special school nearby, which has a nurse on site who can deal with his seizures, but holiday childcare remains a problem.

"I try to explain to people with neurotypical children that their kids can go to an after-school club, or a holiday club by themselves.

"William might get vouchers but he can't go to anything without a carer and they need training."

The Family Fund provides grants for families with disabled and seriously ill children, and the charity said half of its service users cannot meet day-to-day living costs despite being in receipt of state disability benefits.

Amanda has spent her grant on a garden house for William to play in.

Chief executive Cheryl Ward CBE said: "As caring costs increase for families, barriers to paid work as a route out of poverty remain unchanged, including a lack of suitable childcare.

"Until these challenges are addressed, families raising disabled and seriously ill children can't escape the cycle of living in debt, going without essentials like food, clothing and furniture and experiencing poor mental health."

Amanda added: "Everything is so expensive, I wouldn't be able to feasibly buy a garden house for him."

'No choice'

Amanda said that when families have a disabled child their "whole life is caring for them".

She has an older son, Jack, and her partner has two children from a previous relationship.

"You feel guilty for saying it but you feel trapped. They will always be children. It feels like a jail sentence, which is awful to say as they are your kids."

She said a year ago she would cry "every single day".

"It was too much. Not having enough sleep and feeling out of control.

"All you get from people is 'I don't know how you do it'.

"Really, I have no choice. If I break down there is no one else. Unless it gets to a real crisis, there is no help there."

Amanda said she had been proactive in accessing support which had made a difference.

"I use a carers' resource and they are my rock, they do coffee mornings, and the hospice provides counselling and support.

"I found communicating with other parents one of the better things, you just don't feel alone."

Listen to highlights from North Yorkshire on BBC Sounds, catch up with the latest episode of Look North.