Plastic in every level of food web, say scientists

BBC

BBCPlastic pollution is now contaminating insects at the base of terrestrial food chains, raising fresh concerns about the long-term impact on wildlife, according to a new study by the Universities of Sussex and Exeter.

Researchers have discovered fragments of plastic in the stomachs of beetles, slugs, snails and earthworms, with the pollutants making their way up the food chain to birds, mammals and reptiles.

The study, described as the most comprehensive of its kind, analysed more than 580 invertebrate samples from 51 sites across Sussex.

Prof Fiona Mathews, an environmental biologist at the University of Sussex, said microplastics were now "ubiquitous at every level of the food web".

University of Sussex

University of SussexA food web is a complex network made up of all of the food chains in an ecosystem.

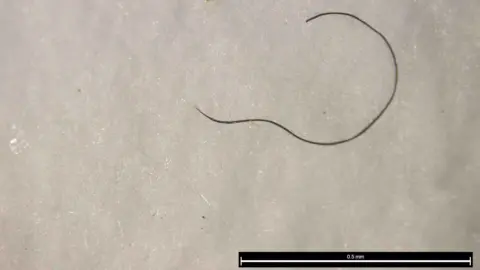

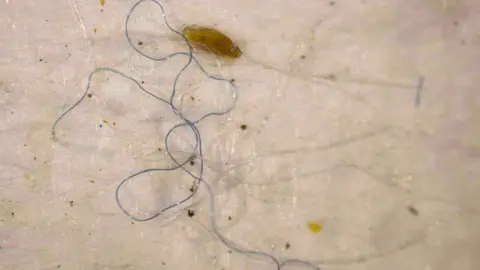

Microplastics were detected in nearly 12% of specimens, with earthworms showing the highest contamination rate at 30%, followed by slugs and snails at 24%, said the university.

Polyester, commonly shed from clothing, was the most frequently detected plastic type.

Lead researcher Emily Thrift, from the University of Sussex, said the findings were "surprising and deeply concerning".

"This is the first study to find plastics consistently turning up across an entire community of land invertebrates," she said.

"Similar plastic types have previously been found in hedgehog faeces and appear to be entering the diet of birds, mammals and reptiles via their invertebrate prey."

The research team warned that plastic pollution should no longer be seen as solely a marine issue.

The team said the chemicals released by degrading plastics in soil pose serious risks to biodiversity, with previous studies linking ingestion of plastic to stunted growth, organ damage and reduced fertility in animals.

Herbivores and decomposers – such as worms and slugs – were found to be the most heavily contaminated.

However, carnivorous insects like ladybirds were also affected, often ingesting larger plastic particles through their prey.

University of Sussex

University of SussexCo-author of the study Prof Tamara Galloway, from the University of Exeter, said: "To reduce the uptake of microplastics into the food web we first have to understand how it is getting there.

"Emily's results are a crucial first step to understanding this process and its consequences for wildlife."

Prof Mathews said the focus has often been on plastics in "visible litter" but added the findings "suggest multiple hidden sources – from clothing fibres to paint particles".

"There is now an urgent need to understand how different types of plastics are affecting ecosystems, and to take steps to reduce their release into the environment," she said,

The researchers say their work, which spans six invertebrate groups and four levels of the food chain, highlights the need for broader environmental monitoring and stronger measures to limit plastic pollution.

Follow BBC Sussex on Facebook, on X, and on Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected] or WhatsApp us on 08081 002250.