New cancer vaccine offers patients hope

BBC

BBCSteve Haycock is one of the first people in the world to be given a cancer vaccine under a ground-breaking trial that changes the approach to the illness.

As he waited for his final dose at Birmingham's Queen Elizabeth Hospital (QE), he shared with the BBC what it meant to be part of the programme, one that could bring fresh hope to patients. He also shared the irony of being involved.

The married 43-year-old has been battling an aggressive form of bowel cancer, and as part of his standard treatment, has had most of his colon removed. Taking part in the trial was, then, a positive, he said. But at the same time, "it's a funny thing to process".

That's because when he was selected, it was on the basis he was deemed at highest risk of his cancer returning. It's a second bite the vaccine is trying to head off.

The process saw samples from his tumour sent away for genetic analysis, after which abnormal proteins produced by the cancer were identified and used to help create the vaccine, which was produced with the same mRNA technology used in several Covid vaccines.

It boosts his immune system to look for the proteins and destroy the cancer cells associated with them.

The hope is it both mops up any cancer cells left after traditional treatment and also trains the body to recognise and destroy cancer cells that might return in the future.

Mr Haycock said he was only the second patient in the UK to have taken part in the trial.

By the time of the vaccine's final dose, he had had almost 20. The first left him with side effects including a high temperature and shaking, he said. They eased after several hours, and faded as the treatment went on.

His last dose was a special day. Coffee, and a cake he made, was shared around his floor at the QE.

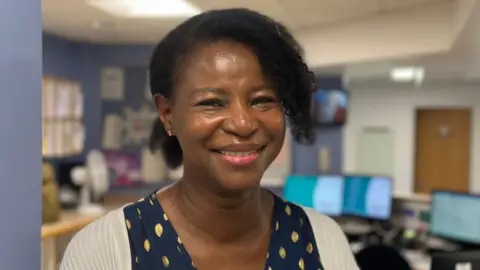

The QE's principal investigator for the trial, consultant clinical oncologist Dr Victoria Kunene, watched Mr Haycock's final treatment - as she promised she would when it started a year ago.

Just 1.3ml was delivered slowly by syringe.

Despite the air of celebration, the doctor said it would be some time before it was known how effective the treatment had been; that's the nature of a medical trial like this.

"It's only by waiting you'll know if it's done the job," she said.

Reuters

ReutersTwo years is a good indicator as to whether things are working. In five years, if patients like Mr Haycock are still cancer free, then we have a potential promising new treatment.

And the signs are good. This approach has already shown promising results in treating advanced skin cancers.

Without the vaccine, Mr Haycock said, "I'd just be waiting for that moment, for it to come back".

"But now I've got the security that I am part of this amazing trial."

Thanks to the doctors, nurses, scientists and patients taking part in the trial, the hope is that one day, treating even the most aggressive cancers may be possible with a tiny syringe.

Follow BBC Birmingham on BBC Sounds, Facebook, X and Instagram.