'Taxi boats' pick up migrants in waist-deep water as Channel smugglers switch tactics

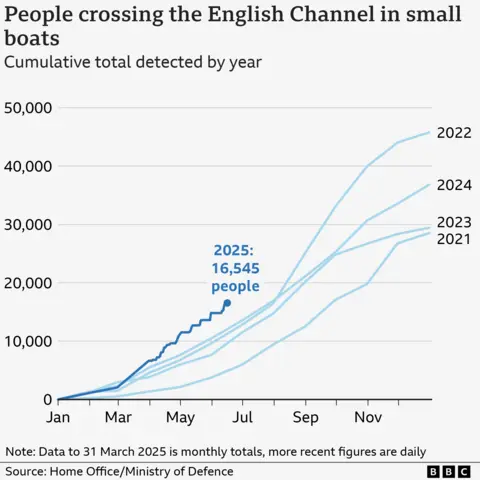

As the weather in the Channel clears, the French police are struggling to halt a potentially record-breaking surge of people from reaching the UK in small boats organised by a growing network of smuggling gangs. Downing Street said on Tuesday the situation was "deteriorating."

Although the French authorities claim they're now intercepting more than two thirds of those boats before they reach the sea, the smugglers are now changing tactics to launch so-called "taxi boats" from new sites, in new ways, and with ever greater speed.

Instead of inflating their boats in the dunes along the coast, close to police patrols, the gangs are launching them from better hidden locations, often dozens of kilometres from the main departure beaches.

They then cruise along the coastline, like taxis or buses, picking up their paying customers who now wait in the sea, out of reach of the police.

Marianne Baisnée/BBC

Marianne Baisnée/BBCJust before sunrise last Friday, we encountered a group of perhaps 80 people gathered in calm, waist-deep water, off a beach near the village of Wissant, south of Calais. There were several women and children in the group, from countries including Eritrea and Afghanistan.

We counted 18 French gendarmes watching them from the shore, declining to intervene.

An inflatable taxi boat, operated by a smuggling gang, had just arrived by sea and now circled repeatedly. Over the course of perhaps 10 minutes, one man sitting at the front of the boat appeared to usher people forwards, to clamber onboard in relatively organised, even orderly, groups.

Several children clung, occasionally crying, to their relatives' shoulders.

"Yes, to England," one Afghan man told me, patiently waiting his turn, his eyes focused firmly on the boat.

The taxi boat system appears to give the smugglers a little more control over what has often been a chaotic and dangerous process, involving large crowds dragging boats to the water and then scrambling on board.

A little over a year ago, I watched the result on a nearby beach when about 100 migrants tried to pile onto the same boat. Five people, including a seven-year-old girl, were trampled or suffocated to death.

Lea Guedj/BBC

Lea Guedj/BBCOn Friday morning, Colonel Olivier Alary stood, dry-footed, watching the taxi boat load up. He explained that the current operational rules for his forces were clear. They would intervene to rescue someone if they were about to drown. They might even attempt to stop the boat if it became trapped on a sandbank. But it was simply too risky, for all involved, for the police to try to reach the boat now that it was afloat.

"The police will be able to do more… if the rules governing our actions at sea are changed," said Alary, referring to the French government's declared intention to revise those rules, possibly in the coming weeks, to give the police more leeway.

The BBC understands French authorities will be introducing a new "maritime doctrine" from the beginning of July which would allow special squads to intercept migrant dinghies up to 300 metres from the shoreline.

"It's essential that we don't create panic and endanger these people further. If the rules change to allow us to intervene against these taxi boats, as close as possible to the shore, then we'll be able… to be more effective," said Alary, as the fully loaded boat finally set off north-westwards, towards the English coast.

Although some officers say there is already a bit of wiggle-room for the police in terms of how strictly they interpret the existing rules, many are fearful that they might face serious legal trouble.

"I can understand an average British person watching this on television might say, 'Damn, those police don't want to intervene.' But it's not like that. Imagine people on a boat panic and we end up with children drowning. The police officer who intervened would end up in a French court. It's a complicated business, but we can't fence off the entire coastline. It's not the Second World War," said Marc Musiol, of the police union, Unity.

"If we don't have the orders, we don't move. Even if there's one centimetre of water, we don't intervene. It's frustrating," said his union colleague, Marc Alegrè.

As a result, the French forces, now patrolling more than 120km (75 miles) of coastline in northern France, focus all their attention on trying to intercept the smugglers' boats before they launch.

And while that interception rate is rising, the smugglers are changing their own tactics fast.

Marianne Baisnée/BBC

Marianne Baisnée/BBCWe'd first joined Colonel Alary and his men soon after midnight on Friday. It was the fourth full night our team had spent on the beaches in recent weeks.

Alary's unit was busy using infra-red drones, paid for by the British government, to spot and track several hundred migrants who'd gathered in smaller groups along the coast, having arrived by bus and on foot over the course of Thursday afternoon and evening.

On a monitor, we could clearly see one group, gathered around a makeshift campfire in a forest near the beach.

"But it's the smugglers we're after. If we move towards the migrants now, they'll just disperse," said Alary.

Then, at around five in the morning, to the visible frustration of the police, reports came in of a successful taxi boat launch further up the coast.

"Let's go," said Alary.

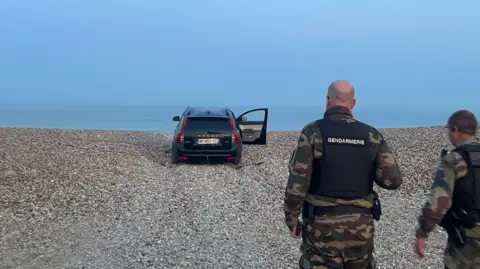

Some minutes later, we arrived at a shingle beach beside the old fishing village of Audresselles, just south of Cap Gris-Nez. A black Volvo V50, doors open, was stuck fast up to its axles in pebbles.

The car had clearly been driven at high speed across the main road and straight towards the sea.

Marianne Baisnée/BBC

Marianne Baisnée/BBC"They're adapting, again," said Colonel Olivier Alary, inspecting the black cords that the smuggling gang had used to tie a large inflatable boat, precariously, to the Volvo's roof.

The smugglers had evidently inflated the boat in a shed or farm building close by, then driven it the short distance to the beach, untied it, dragged it the last few metres to the water, and were safely on their way within a matter of seconds. Heading north, they would collect their paying passengers from other points along the coast much like bus or a taxi – hence the "taxi boat" nickname.

"This is the third time it's happened in this area," grumbled Alary, of an emerging new tactic used by the smugglers.

The police, armed with night-vision binoculars and drones, have become skilled at spotting the moment the smugglers start to inflate their rubber boats. This normally happens in the dunes and forests on the coast or beside rivers and canals. It is a period of maximum vulnerability for the gangs and their clients.

Using up to six electric pumps per boat, the smugglers can often finish the job in less than 15 minutes. But the inflated boats are large, unwieldy, and hard to move by hand.

The police often have time to intercept the inflatables before they're dragged towards the water, usually by a dozen or more people. Officers, sometimes using pepper spray and stun grenades to clear a path, then slash the boats with knives to render them unusable. The BBC has seen police body-cam footage showing people hurling rocks at officers and even holding a young child in front of the police to try to stop them.

According to the French police, the gangs – which we understand are now growing in number in the Calais area as demand for crossings increases – have not only begun inflating their boats in secrecy, hidden in buildings close to the beaches, but have threatened local farmers who have objected to their presence.

While some of these taxi boat launches – designed to exploit the French police's unwillingness to intervene at sea – take place close to the main migrant departure areas around Calais and Boulogne, some boats are now setting off from much further away.

On Friday morning, Alary told us, there had just been a successful taxi boat launch from Cayeux-Sur-Mer, a village about 100km south beyond the river Somme. He anticipated that it would arrive here around noon and start trying to pick up passengers near Boulogne.

One unintended consequence of the smuggler's growing dependence on the taxi boat system is that it gives young men an advantage over women and children, who often struggle to climb on board from the sea.

"I've tried [to cross] 12 times now," said Luna, a Somali woman from Mogadishu. She described incidents of police violence on the beaches and the experience of being left behind while men clambered onto the boats.

"Sometimes the police are very violent. I've been hit myself. They put tear gas – something in the air – you can't breathe. Sometimes the boat is very far [out to sea]. That's why women and children are left behind so many times. It's so dangerous, so risky. We cannot swim. I don't want to die," Luna said, as she waited for a meal at an informal migrant camp near Dunkirk.

She added that after one and a half months trying to complete the journey to the UK, she had no plans to quit.

Meanwhile, having failed to stop the taxi boat launch on the shingle beach at Audresselles, Colonel Alary was not yet ready to give up either.

"Let's go. The boat is going north towards Cap Griz Nez. We're going to try to intercept them," he said, as his team rushed towards their cars.

While we followed the police, we could see the boat – a thin black smudge on a milky sea – to our left. But by the time we'd got to Wissant, 15 minutes later, it was already too late. The migrants were in the water, and the taxi boat was already half full.

All in all, it had not been a good night for the French police. Alary's forces claimed four successful interceptions on land. But along the whole coast, a total of 14 boats had made it to sea, carrying 919 people to the UK.

Marianne Baisnée/BBC

Marianne Baisnée/BBCLater that morning, on a brief trip to sea on a police patrol boat, Colonel Alary reflected on the battle to stop the smugglers.

There were so many challenges – from the heavy equipment worn by police which made it dangerous for them to enter the water safely, to the inherent instability of the inflatable boats, which made them too vulnerable to stop at sea without risk of drownings.

But Alary said the UK itself held the key to solving this crisis.

"It should be kept in mind that 30% of all the migrants entering the European Union end up here, in the Calais area. They travel from all over Europe to come here… because the United Kingdom is attracting them. England is attractive. It encourages migrants to want to join it. The solution is to make England less attractive, then people would remain [at home or in the EU]."

That belief - in the UK's magnetic pull for migrants – remains the conventional wisdom among both French officials and many of those risking their lives to cross the Channel.

On a much windier day last week, on a beach beside an old Bourbon-era fort in the village of Ambleteuse, I met a former fisherman, Stéphane Pinto, who is now the local mayor.

"For migrants, the UK is still seen as an El Dorado. The British need to address this issue more forcefully," he said. If it didn't, Pinto warned of growing violence between police, local communities, and a rising wave of migration from an increasingly troubled world.

"This is no longer just a problem linked to dictatorship or war. It is growing due to what's happening globally: climate change, the collapse of economies in some countries, and so on. We feel there is a new wave growing today, and unless we really tackle it, we will sadly only be spectators of what will happen in the coming years."