Trump's tariffs could be death knell for US-Africa trade pact

AFP

AFPThursday was a "terrible" and "devastating" day for people involved in Lesotho's textile sector as they digested the news that the country's exports to the US would be hit by a 50% import tax, or tariff.

Teboho Kobeli, who founded Afri-Expo Textiles and employs 2,000 people in the country, could barely disguise his distress as he told the BBC about the impact of potentially losing a huge chunk of the US market because the prices of his goods will have to increase.

The small southern African nation has become the poster child for the African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa) – a 25-year-old piece of US legislation guaranteeing duty-free access to American consumers for certain goods from Africa.

Considered the cornerstone of US-Africa economic relations, the aim was to help industrialise the continent, create employment and lift dozens of countries out of poverty.

It was based on a philosophy of replacing aid with trade.

The act's overall impact is debateable but it has been credited with creating hundreds of thousands of jobs, particularly in the textiles sector.

Though President Donald Trump did not mention it by name, Agoa's status is now uncertain.

Like so much that has come out of the White House in the whirlwind first few weeks of his presidency, Wednesday's announcement has sown confusion – especially, in this case, in Africa.

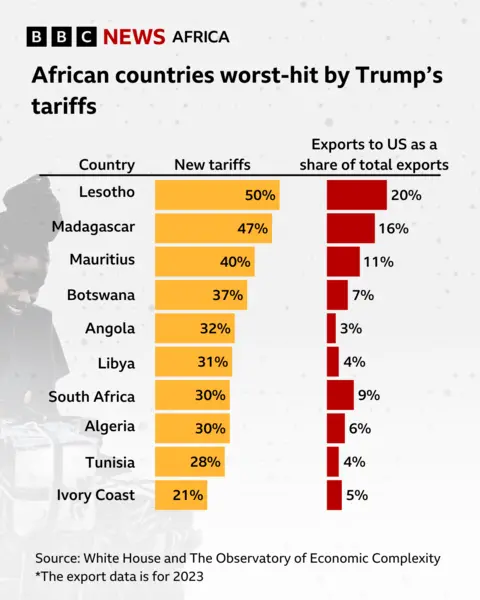

On the one hand there is Agoa, with its tariff-free arrangement, and on the other there is Trump outlining tariffs ranging from 10% (including Kenya, Ethiopia and Ghana) to 31% (South Africa) and 50% (Lesotho).

Which takes precedence?

South Africa, which exports metals and cars to the US, believes this spells the end of Agoa.

"The reciprocal tariffs effectively nullify the preferences that sub-Saharan Africa countries enjoy under Agoa," South Africa's foreign and trade ministers said in a joint statement on Friday.

AFP

AFPBut Kenya's Principal Secretary for Foreign Affairs Korir Sing'oei had a different take.

"It is our considered view that until the law lapses end of September 2025 or unless repealed earlier by Congress, the new tariffs imposed by President Trump will, in any event, still not be immediately applicable," he said in a statement.

Kenya, which exports clothes to the US, has tried to put a brave face on the issue, saying that as it was not hit as hard as other textile exporters, such as Vietnam and Sri Lanka, it would still have a competitive advantage.

Whatever happens to Agoa in the immediate term, it seems that Trump's sweeping tariffs have scuppered hopes of the legislation being renewed.

The Clinton-era law, which in the current climate is beginning to feel like a relic of a bygone time, was up for renewal later this year.

Since 2000, certain African countries had duty-free access to the US market for a raft of goods including clothing and textiles, cocoa products and wine, as well as crude oil.

The access was tied to a number of conditions including free market policies, labour and human rights and political pluralism. Thirty-two countries from sub-Saharan Africa were eligible as of last year.

In 2023, two-way trade under Agoa totalled $47.5bn (£36.4bn), with the US exporting $18.2bn billion worth of goods and imports amounting to $29.3bn.

By virtue of being among the continent's largest economies, South Africa and Nigeria have dominated trade under the act, but Lesotho has taken full advantage and has become a significant exporters of garments to the US, supplying brands such as Walmart, GAP and Old Navy.

AFP

AFPBut a future without Agoa – for Lesotho and others – presents big challenges.

If nothing changes, "a tariff of 50% sounds like a death knell to the Agoa manufacturing in Lesotho", says Mukhisa Kituyi, a former secretary-general of the UN Conference on Trade and Development and a former Kenyan trade minister.

In 2018, the World Bank modelled a scenario where Lesotho experienced the sudden loss of Agoa privileges and found that the impact would "reach 1% of GDP" within two years. The report concluded that impact on welfare would be "dramatic."

But, as witnessed with the aid cuts, arguing about the human impact or fairness will not fly in the current set-up, in the face of "disruptive populism and post-fact, post-truth society", Dr Kituyi argues.

He thinks countries, like Kenya, that have the new tariffs set at 10% could still try to hold ground in the US market, with the exporters and their American importers negotiating how to absorb the new taxes without raising prices for the consumer too much.

As Dr Kituyi was involved in trade negotiations, including Agoa, he has seen first-hand the effort that goes into "fine-tuning these processes" to create a "shared benefit from stable, predictable rules-based trading".

But now, he reckons, such agreements are "hostage to the wishes of the dominant political group in America".

Michelle Gavin, a senior fellow for Africa policy studies at the Washington-based Council for Foreign Relations, said the way the new tariffs have been calculated "makes no sense at all" to economists.

It's difficult to sort of see "any kind of clear strategy or intention," from the Trump administration so far, she tells the BBC.

But the decisions will only exacerbate the loss of American influence in Africa, she warns. China, already the continent's biggest trading partner, could take further advantage.

"It looks like a withdrawal, an ignoring of an entire huge region of the world," Ms Gavin says.

Coming shortly after the Trump administration severely pared back the US Agency for International Development, leading to the cancelation of both humanitarian and life-saving health assistance, the analyst says America appears to be "destroying its own instruments of influence with abandon now".

Agoa has long been viewed as an important tool of US soft power, especially in countering the growing influence of China and Russia in Africa.

There has in the past been bipartisan support for it among American legislators, and Dr Kituyi sees this as "a glimmer of hope".

A bill seeking a renewal of Agoa until 2041 was released by Democrat Senator Chris Coons over a year ago, but it may not make any progress in the current Congress.

Ms Gavin does not believe that Agoa is now a priority given the global upheaval Trump's drastic and unpredictable policy shifts have created.

"I think a non-reciprocal trade agreement is a very tough sell for this Congress, which is dominated by the Republican Party that has thus far been quite accommodating of the administration's agenda."

She believes that while it "makes good sense as a matter of policy," it is unlikely to be front and centre of legislators' agenda "as a matter of politics" even if Congress starts to assert itself more.

As Trump's tariffs throw the world into turmoil, the specific needs of the continent are unlikely to be uppermost for others around the world.

If Agoa does become defunct, Africa will have to look within itself and make good on the promises of creating a continental free-trade area. It will also have to work harder to find new trading partners or expand existing markets.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBCGo to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica