The bombed London church that was reborn in the USA

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs Londoners celebrated VE Day nearly 80 years ago much of the city in which they lived lay in ruins, not least the historic places of worship built by Sir Christopher Wren in the late 1600s in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London.

While some would be repaired or rebuilt, others remained as shells, transformed into small public parks surrounded by a single wall or tower. However, one had a very different ending, being moved brick by charred brick more than 4,000 miles away and rebuilt at a college in the US Midwest.

Why did St Mary Aldermanbury end up across the pond and what is it used for now?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile St Mary Aldermanbury may have been destroyed in the Blitz, it wasn't the first time disaster had struck.

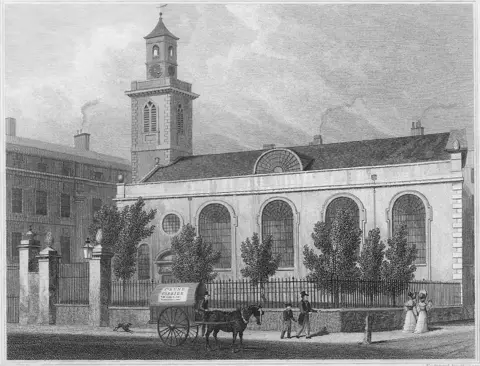

Having been founded around the start of the 12th Century, the original medieval church was destroyed in the Great Fire in 1666, then became one of the 52 sites, including St Paul's Cathedral, rebuilt by Wren.

On 29 December 1940, St Mary Aldermanbury and seven other City churches were badly damaged during a particularly devastating night of the Blitz as waves of Luftwaffe planes dropped bombs over London in what some coined as "the Second Great Fire".

With limited finances available in post-war Britain to do anything with it, the church remained a charred husk for two decades - until an unusual proposal arrived from Missouri.

"It really dates back to the end of the war on VE Day, when Sir Winston Churchill gave his famous speech on the balcony saying 'this is your victory' to the British people," explains Timothy Riley, director and chief curator of America's National Churchill Museum.

"It was a triumphant moment for all at the end of the war. But not long after there was a general election and Churchill's party lost."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the wake of that defeat, Britain's wartime leader received a letter from Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, inviting him to give a speech, which included a message from US President Harry Truman saying: "This is a wonderful school in my home state. If you come, I'll introduce you."

"I'm convinced that letter would normally have been given to a secretary by Churchill with the instruction to politely decline or refuse," Mr Riley says.

"However, when he saw this handwritten note... having just lost an election and knowing that he had more to say, he anxiously/eagerly accepted the invitation and made his way to Fulton to give the Iron Curtain speech."

The famous address, delivered on 5 March 1946, spelt out the deepening tensions between the West and the Soviet Union, and called for a special relationship to be forged between the US and UK.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFifteen years on from the speech, and with Churchill now in his 80s, thoughts turned to how the college could commemorate it.

"Someone suggested a garden, someone suggested a statue, a plaque, and then the president of the college Robert Davidson said: 'Why don't we bring a ruined Christopher Wren church that was bombed in the Blitz, left abandoned for nearly 20 years in the City of London and rebuild it in Fulton?'," says Mr Riley.

"The reaction, of course, was bafflement; how could we do such a thing? But that's what happened in the 1960s."

After the initial suggestion was made in spring 1961, efforts began in earnest to gain permission to relocate the building and raise the $1.5m (the equivalent of more than $16m or £12m today) needed to do so.

Backing was gained from several influential sources. President John F Kennedy became the project's honorary chairman until he was assassinated in 1963, with his successor Lyndon B Johnson then taking on the role. Previous presidents Truman and Dwight Eisenhower also publicly supported the cause.

Back in the UK, Churchill endorsed the scheme, writing in a letter that it was an "imaginative concept", and following extensive discussions both the City of London and Diocese of London approved the move.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 1965 what remained of the church was dismantled piece by piece, with each of the 7,000 stones cleaned and then numbered so they could be placed in the same formation in their new home.

Weighing more than 600 tonnes in total, they were taken by ship to Virginia, before being transported by rail to Missouri where the tricky task of rebuilding a wrecked 300-year-old building began.

The Times branded it "one of the most intricate jigsaw puzzles in the history of architecture" and the project's mason, Eris Lytle, later described how he had to learn skills once used by Renaissance craftsmen to complete the project.

Getty Images

Getty Images Tim Riley

Tim RileyWith the monument completed in 1969, a service was held on 7 May to rededicate the church, attended by dignitaries from both sides of the Atlantic - although not Churchill who had died in 1965.

Today, St Mary Aldermanbury isn't an active church but forms part of America's National Churchill Museum, based on the Westminster College campus. Yet as Mr Riley points out, it does maintain at least one link to its previous life.

"It's a popular destination wedding venue - and also where you don't have to have a passport to get married in a 'British' church."

He says the building is "perhaps the top tourist attraction in the middle of Missouri", and while those living in the area generally know about its history, "we still have a lot of people saying: 'I had no idea, it's extraordinary.'"

As for the church's original site, beside the Guildhall, today it is a small park tucked among towers and modern office blocks of the City of London. Benches, trees and plant life surround a few remaining stones, while a large granite slab marks where the altar once stood.

The site was refurbished last year with some of the funding coming from the museum, which also recently completed restoration work at St Mary Aldermanbury.

"We've invested nearly $6m (£4.5m) into the preservation of the church so that we continue to be good stewards, so that it'll thrive and inspire and inform generations to come," says Mr Riley.

Reflecting on the relocation of a bombed church to another continent, he believes it has become much more than a memorial to Churchill's Iron Curtain speech.

"It is, I think, an extraordinary symbol of the Anglo-American relationship... and a constant reminder of the bond that our two countries continue to share in our own histories."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected]