The great conclave secret: What do would-be popes eat?

Alamy

AlamyFor more than 750 years, strict rules have guarded what cardinals can and cannot eat to prevent hidden messages stuffed inside chicken, ravioli and napkins.

This past week, travellers in Rome may have spotted cardinals frequenting their favourite restaurants. Just before the last papal election in 2013, Italian media reported that many of these men were making the time to visit a particular neighbourhood favourite, Al Passetto di Borgo, a family-run eatery located 200m from Saint Peter's Basilica, where Cardinal Donald William Wuerl is known to order the lasagna and Francesco Coccopalmerio (allegedly the most-voted Italian cardinal in 2013) likes the grilled squid.

Cardinals may feel some urgency to get in a good meal or two because, during the conclave beginning on 7 May, in which 135 cardinals will hold a secret election for a new pope in the Vatican's Sistine Chapel, they'll be entirely secluded from the rest of the world for an indefinite period of time. Voting, sleeping and eating all take place in tightly controlled sequestration.

Papal conclaves are notoriously secretive affairs. The cardinals are secured in a single shared space with no messages allowed in or out, except for the smoke signalling whether a vote has been successful. White smoke signals a new pope and black means another vote is required to reach the two-thirds-plus-one consensus required to crown a new pontiff. What precisely occurs in these conclaves is unknown, but one thing is certain: the cardinals must eat over the days or weeks it takes to elect the new leader of the world's 1.4 billion Catholics.

Alamy

AlamyBut with provisions going in and out, how is the secrecy of the conclave maintained? How can the cardinals ensure the integrity of the vote, unaffected by outside opinion?

Historically, food has presented a potential risk: a cardinal's ravioli might be stuffed with an illicit message from the kitchen staff; or a cardinal could sneak a vote update to the outside world with a dirty napkin. However, communal eating is also one of the contexts in which furtive negotiations can take place. Recent pop culture representations have made the most of this, using conclave food culture to create a heightened sense of suspicion, intrigue and control.

World's Table

BBC.com's World's Table "smashes the kitchen ceiling" by changing the way the world thinks about food, through the past, present and future.

Take the 2024 film Conclave, where almost all the plot points occur not in the voting chambers, but in the cafeteria. The noisy meals contrast with the almost entirely silent conclave proper, which proceeds without formal debates. The otherwise silent voting is only sparingly punctuated by moments of ritual speech, like the audible oath a cardinal takes as he drops his voting card into the ballot urn. Still, around the ceremonial silence is a great deal of communication, much of which happens with and via food. And while we can't assume that the film faithfully depicts what happens behind closed doors, it is no doubt true that in papal food culture – as in culture more broadly – what you eat, how you eat and with whom you eat speaks volumes.

The code of conclave secrecy goes back to 1274, when Pope Gregory X established the regulations that still partly dictate how papal elections are run today. As with the coronation of many popes, his was controversial. It also had the distinction of being by far the longest, taking almost three years (1268-1271) to reach the majority consensus required to appoint a new pope. According to Italian canonist Henricus de Segusio, who served in that conclave, local residents threatened to restrict the cardinals' food to hasten a resolution.

Alamy

AlamyPope Gregory X's new rules included isolation of the conclave – a rule that is still in effect today – and rationing of the cardinals' food. After three days without consensus, the cardinals received only one daily meal; after eight days, only bread and water. In the mid-1300s, these rules were relaxed by Clement VI, who permitted three-course meals consisting of soup; a main dish of fish, meat or eggs; and dessert, which could include cheese or fruit. While the rationing didn't stick, tight control over conclaves remains.

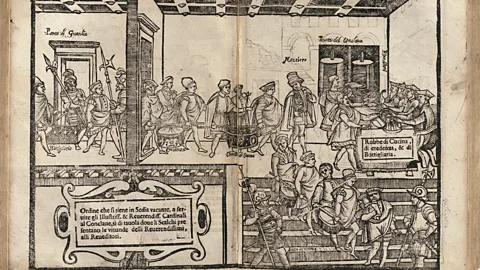

The most detailed historical account of the food culture of papal conclaves comes from Bartolomeo Scappi, who was the Renaissance's most famous chef (and arguably the world's first celebrity chef) and served both Popes Pius IV and Pius V. His 1570 book, Opera Dell'Arte del Cucinare (The Art of Cooking) – the first cookbook published by a practicing chef – catapulted him to fame. In it, he reveals the secrets of feeding the conclave that elected Pope Julius III, and the extreme practice of surveillance that remains to this day.

More like this:

• Testaccio: The foodie neighbourhood where Romans go to eat

• Where Rome's insider foodie Katie Parla queen eats in her hometown

According to Scappi, the cardinals' daily meals were prepared in a communal kitchen by cooks and sommeliers, just two of the many domestic positions that kept a conclave functioning. He identifies that the kitchen was a space where illicit messages could be shared, and notes that guards were stationed there specifically to prevent this. Therefore, twice a day in an order determined by lottery, stewards would ceremoniously bring the food to the ruota. This "wheel" or turntable, built into the wall, allowed food and drink to be passed to the cardinals in their inner hall. Before being passed through the wall, food and drinks were checked by testers to ensure they were not hiding any illicit messages. Every step was closely watched by Italian and Swiss guards.

Folger Shakespeare Library

Folger Shakespeare LibraryThe foodstuffs were strictly controlled, with nothing permitted that might obscure a secret message. No closed pies. No whole chickens. Wine and water had to be offered in clear glass, not in opaque vessels. Cloth napkins were opened and carefully inspected.

This arrangement was partly to ensure the complete isolation of the cardinals, and partly to assuage concerns about poisoning. After all, especially during the Renaissance, the papacy was a highly influential political position.

Strict protocol and food restrictions aside, the meals Scappi describes sound bountiful and balanced, including salad, fruit, charcuterie, wine and fresh water. Likewise, he describes comfortable accommodations for the cardinals. Each had their own large cell, decorated with silk and amply furnished with a bed, a table, a clothing rack, two stools, a chamber pot and a lockable jar, among many other items. By Scappi's account, serving in a Renaissance papal conclave wasn't a bad gig – so long as you didn't mind constant surveillance.

For the upcoming conclave starting on 7 May, the nuns at the Domus Sanctae Marthae – the modern residence where cardinals live during their sequestration – will prepare simple dishes characteristic of Lazio, the Italian region surrounding the Vatican, and nearby Abruzzo: minestrone, spaghetti, arrosticini (lamb skewers) and boiled vegetables. While this may seem to differ from Renaissance conclaves where meals were prepared by secular domestics operating under strict protocol and close guard, the result is the same: the process is closely controlled, ensuring no information can get in or out.

Alamy

AlamyIn the first of several kitchen scenes that appear in Conclave, the film makes a point of showing nuns boiling whole chickens for broth – hardly luxurious fare. But it's the symbolism that's important. The modern Catholic church – especially coming out of the leadership of Pope Francis – hopes to communicate a simple, wholesome image. Concerns about the potential for food (whole chickens, specifically) to contain literal secret messages have faded. It's illicit communication through electronic means, another recurring symbol in the film, that's the concern now.

So, while the Vatican is being swept for hidden electronic devices in preparation for the upcoming conclave, the cardinals will do their own personal preparations, venturing into Rome to linger over a favourite dish or two, perhaps wondering whether it will be their last supper before becoming pope.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.