U-July 22: Is it too soon to make a film about a tragedy?

Alamy

AlamyA new feature film showing at the Berlin Film Festival deals with the actions of mass murderer Anders Breivik and some say it's in bad taste, writes Emma Jones.

A teenage girl sprints through woods. She is running for her life. She trips over branches, and sees the dead body of a child. The air is full of gunshots.

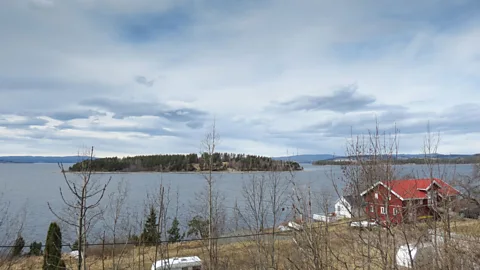

This is not a scenario from, say, The Hunger Games. This is Utøya 22 Juli, also known as U-July 22, a film which deals with the actions of Anders Breivik, a far-right extremist who murdered 69 young people enjoying summer camp on the Norwegian island of Utøya, on 22 July 2011. He had also killed eight others when he detonated explosives earlier that day in the capital, Oslo.

The massacre was seven years ago – and now it’s been made into a film in competition at this year’s Berlin International Film Festival. Some say it’s too soon to make a feature film out of such horror.

“The opposition to making this film was no secret,” says director Erik Poppe, a four-time Norwegian National Film Critics' Award winner. “There was a lot of reaction when people found out and I am the first one to understand, as I would have thought myself, ‘is that possible? Is it going to be an entertainment movie?’”

Poppe, a former war photographer, filmed Utøya over five days near the original location of the murders, with a cast of young, mainly amateur actors. He filmed one take each day – each lasting 72 minutes, the exact length of Breivik’s attack, before help arrived. There is little editing and no music in the film. No promotional trailers have been released. It was first screened to survivors and their families, and Poppe took feedback from them. And Anders Breivik never features in the film – merely as a shadowy figure in the distance, once.

Alamy

AlamyMany in the audience, and the press attending the festival, reported themselves ‘stunned’ into silence, or tears, by Utøya, which received a 10-minute standing ovation. But in a week when a lone gunman killed 17 people in a shooting at a high school in Florida, could watching a recreation of recent real-life mass murder inspire a different emotion in someone watching the film?

“Of course, there might always be a lunatic that could get inspiration from watching this, but he or she could equally get that from watching the news as well,” points out Gunnar Rehlin, a film journalist for Swedish national news agency TT. “Some people will still say the film’s in bad taste, but having seen it, it is not. It is very well done.”

According to Poppe, “no time is a good time” to make a film about real-life trauma.

“I respect those who think it’s too early, but for those who lost loved ones, they feel it like it was yesterday, seven years on. It will never be the right time. And many survivors are concerned that the memory of what happened is fading away. There’s a lot of focus on the killer, on what kind of official memorial Norway will have. It felt urgent to bring the actual story back into the collective memory.”

Matt Mueller, editor of Screen International, agrees that artistic responsibility can only go so far before freedom of expression is stifled.

“Hasn’t art always been about processing human trauma and making sense of the senseless?” he asks. “It’s been the same throughout history, and film is part of that tradition. I don’t believe in this idea of ‘too soon’ for film. I believe in due diligence.”

Stranger than fiction

However, historically, when film-makers have come calling a few years after tragedies on US soil, public reaction has been critical. When Paul Greengrass, a respected British director, made United 93 in 2006, about passengers who fought back against the 9/11 hijackers just five years before, some audiences were reported to be shouting at the screen. During the making of Patriot’s Day, a 2016 film directed by Peter Berg about the hunt for the Boston Marathon bombers, large areas of the city were locked down. Recreations of police Swat teams - who had been there in reality just three years before - laid Hollywood open to accusations of profiting from trauma.

Alamy

Alamy“It's a sensitive subject. I was really on the fence and kind of reluctant to commit,” Mark Wahlberg, the film’s star, told the press at the time. “Then I realised, they're going to make the movie anyway; I might as well be in control of it."

Within 18 months of the Boston marathon bombing there were three Hollywood projects in development about it. In fact, time passing can make a movie retrospective of real-life tragedy less likely until a generation has passed. Oliver Stone made World Trade Center in 2006, starring Nic Cage, about two officers trapped during the 9/11 attacks, and Greengrass made United 93, but now, nearly two decades after the event, as yet there is no ‘definitive’ film planned.

Alamy

Alamy“With an event on that scale, how can you approach it?” Mueller points out. “It would be quite daunting. The ramifications associated with making it are so strong, and the studios have different incentives to independent film-making. They would need to put a lot of money into that kind of project.”

But waiting 30 or 40 years before dealing with a real-life event often means a film-maker arrives at a more “truthful” perspective, according to José Padilha, the director of 7 Days in Entebbe, a feature film also showing in Berlin, about Israel’s attempts to rescue 240 hostages trapped in Entebbe, Uganda, in the summer of 1976.

“Immediately after what happened a lot of the film-making produced was very euphoric, it was seen as a great military victory,” Padihla explains. “With time passing, new insights come. Our perspective – that the kidnappers never intended to kill the hostages – wasn’t in the official narrative from 1976. But we’ve checked it out with eyewitnesses, and we believe it’s true.”

Alamy

AlamyErik Poppe’s Utøya 22 Juli is a fictional film drawing extensively on interviews with survivors; the character it follows, Kaja, played by Andrea Berntzen, isn’t real. Poppe also believes film can be “more truthful” than a documentary.

“By discussing it with so many people we could bring it all together, compared to telling one or two stories, which is what you’d get in a documentary,” he claims.

While every actor and crew member in Utøya 22 Juli had access to a psychologist and counselling before, during and after filming, Poppe says he will have failed if the audience who choose to watch the film don’t find it, at the very least, uncomfortable.

“I think if it’s not hard it’s not real,” he says. “There aren’t too many films that show this side of life. I wanted the audience to learn something about what’s out there and feel the pain, and see what extremism looks like, and then figure out what we can do as a society. I suggest we all have a responsibility to look for the individuals who don’t feel part of us, who are prey for extremists.”

However, films about extremists such as Anders Breivik might provoke even greater debate than Utøya 22 Juli – and Paul Greengrass has one in production, called Norway, due to be released sometime later this year. Whether individual terrorists should have that kind of publicity is another argument for the film industry, according to Gunnar Rehlin.

“Since Breivik seems to thrive on attention, that might be a film that one might wish had not been made,” he says.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.