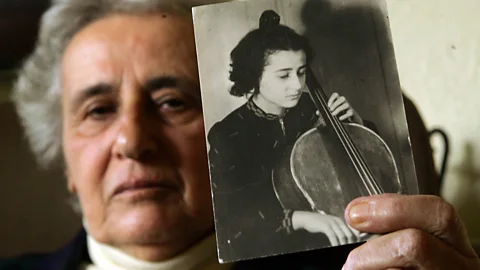

'It was an escape into excellence': How music saved the life of a teenage Jewish cellist in Auschwitz

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Nazi extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau was liberated by Soviet troops on 27 January 1945. Anita Lasker, a Jewish teenager, managed to survive there simply because the camp orchestra needed a cello player.

Now aged 99, Anita Lasker-Wallfisch is the last remaining survivor of the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz. At the age of 19, she was interviewed by the BBC on 15 April 1945, the day of the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen death camp where she had been transferred six months earlier. Interviewed in German, the language she grew up speaking, she said: "First, I would like to say a few words about Auschwitz. The few who have survived are afraid that the world will not believe what happened there."

Warning: This article contains graphic details of the Holocaust

She continued: "A doctor and a commander stood on the ramp when the transports arrived, and sorting was done right before our eyes. This means they asked for the age and health condition of the new arrivals. The unsuspecting newcomers tended to report any ailments, thereby signing their death sentences. They particularly targeted children and the elderly. Right, left, right, left. To the right was life; to the left, the chimney."

When she first arrived at the Auschwitz unloading platform known as the ramp, her casual comment that she played the cello was enough to change the direction of her life. "Music was played to accompany the most terrible things," she said.

The then Anita Lasker barely spoke German in public again for 50 years after World War Two, but when she was growing up, her hometown of Breslau was part of Germany. Now known as Wrocław, it has been part of Poland since the end of the war. Lasker's mother Edith was a talented violinist and her father Alfons was a successful lawyer. As the youngest of three daughters, she grew up in a happy home where music and other cultural pursuits were encouraged. She knew at an early age that she wanted to be a cellist, but outside the sanctuary of her family home, darker forces were stirring.

She recalled on a BBC television documentary in 1996: "We were the typical assimilated German-Jewish family. We went to a little private school, and I suddenly heard, 'Don't give the Jew the sponge,' and I thought, 'What is all this?'"

By 1938, as antisemitism took hold in Nazi Germany, Lasker's parents couldn't find a cello tutor in Breslau who would teach a Jewish child. She was sent to Berlin to study, but had to rush back to her parents after a night of murder and mayhem. On 9 November 1938, the insidious persecution of Jewish people turned violent as Nazis smashed the windows of homes, businesses and synagogues on Kristallnacht or "the night of broken glass".

Back at home, Lasker's parents continued to instil a love of culture in their children, as "nobody can take that away from us". Her eldest sister Marianne escaped in 1939 on the Kindertransport, the mission which took thousands of children to safety in Britain just before the war. By 1942, even as "the world was falling to pieces", her father still had Anita and her sister Renate discussing sophisticated works such as Friedrich Schiller's tragic play Don Carlos. However, it was "obvious what was going to happen", she said.

Arriving in hell

In April 1942, the dreaded order came for her parents to report to a certain location within 24 hours. "We walked through Breslau, not just my parents but a whole column of people, to this particular point and said goodbye. That was the end. I only understood what my parents must have gone through when I became a parent myself. By then, one had already started to suppress the luxury of feelings."

Anita and Renate were sent to a Jewish orphanage, but they soon hatched a plan to escape from Nazi Germany. Posing as women on their way home to unoccupied France, they set off with two friends for Breslau railway station clutching forged papers. The plan failed and they were arrested by officers of the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police force. Anita served about 18 months in jail on charges of forgery, aiding the enemy and attempted escape, but at least she was relatively safe there. "Prison is not a pleasant place to be in, but it's not a concentration camp," she said. "Nobody kills you in a prison."

In 1943, because of overcrowding in Breslau prison, any remaining Jewish people were relocated to concentration camps. Anita was put on a train to be taken to Auschwitz, and Renate was sent two weeks later. Anita arrived in the camp at night to find a terrible scene: "I remember it was very noisy and totally bewildering. You had no idea where you were. Noisy with the dogs, people screaming, a horrible smell... You'd arrived in hell, really."

Upon arrival, she was tattooed and shaved by Auschwitz prisoners who were eager for any news about the war. "I said, 'Look, I can't tell you too much because I've been in prison for a long time,' and casually mentioned that I played the cello. And this girl said, 'Oh, that is very good. You might be saved.' The situation was unbelievable, really. I was naked, I had no hair, I had a number on my arm, and I had this ridiculous conversation. She went and got Alma Rosé, who was the conductor of the orchestra, so I became a member of the famous Women's Orchestra."

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Subscribe to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

Alma Rosé was a niece of composer Gustav Mahler, while her father was leader of the Vienna Philharmonic. The violinist ran the camp orchestra with fearsome professionalism, according to Lasker: "She succeeded in making us so worried about what we were going to play and whether we were playing well that we temporarily didn't worry about what was going to happen to us."

Using instruments stolen from other people who had been brought to the camp, the orchestra played its limited repertoire of military music. "Our job was to play marches for the columns that worked outside the camp when they marched out, and in the evening when they came back in," she said.

Speaking on BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs in 1996, Lasker said that while Rosé set "enormously high standards", she did not think it was because of a fear of being murdered if they failed to play well. "It was an escape somehow into excellence," she said. "Somehow you come to terms with the fact that eventually they're going to get you, but whilst they haven't got you, you just carry on. I think one of the ingredients of survival was to be with other people. I think anybody on their own really didn't have a chance."

From Auschwitz to Belsen

Rosé did not survive the war, dying of suspected botulism in April 1944. Lasker said: "I think we owe our lives to Alma. She had a dignity which imposed itself even on the Germans. Even the Germans treated her as if she were a member of the human race."

The music stopped in October 1944 when the women were transferred to Belsen, a concentration camp where there was no orchestra. Conditions there were unimaginably awful. Lasker said: "It wasn't actually an extermination camp – it was a camp where people perished. There were no gas chambers there, no need for gas chambers – you just died of disease, of starvation."

The liberation of Belsen by British troops in April 1945 saved her life. "I think another week and we probably wouldn't have made it because there was no food and no water left," she said.

More like this:

• The man who saved 669 children from the Nazis

After the war, Anita and Renate contacted their sister Marianne in the UK, and in 1946 they both settled in Britain. Renate went on to work as an author and journalist, moving to France with her husband in 1982. She died in 2021, 11 days shy of her 97th birthday. Marianne, the eldest sister who was brought to safety on the Kindertransport, died in childbirth soon after the war. "Such are the ironies of fate," she told the Guardian in 2005.

Anita pursued a career as a successful musician, becoming a founder member of the English Chamber Orchestra. On a visit to Paris, she was put in touch with Peter Wallfisch, a piano student and fellow refugee whom she remembered from her school days in Breslau. They married in 1952 and had two children, cello player Raphael and psychotherapist Maya. While Lasker and her husband communicated with each other in "a total mixture of languages", she admitted that "it would have been totally impossible for me to speak German to my children".

For decades, she vowed never again to set foot on German soil, fearing that anyone of a certain age could have been "the very person who murdered my parents". With the passage of time, she softened her stance, and by 2018 she was invited to Berlin to address politicians in the Bundestag, the German parliament. She said: "As you see, I broke my oath – many, many years ago – and I have no regrets. It's quite simple: hate is poison and, ultimately, you poison yourself."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.