Crumbling rocks, wetter avalanches: Why life-and-death rescues are changing in a warming world

Italian Mountain and Cave Rescue Service, Gianluca Vanzetta

Italian Mountain and Cave Rescue Service, Gianluca VanzettaSkiers, climbers, cyclists and even mushroom-pickers face surprising new risks in the mountains – and so do those who rescue them. But scientists are working on ways to keep us all safe.

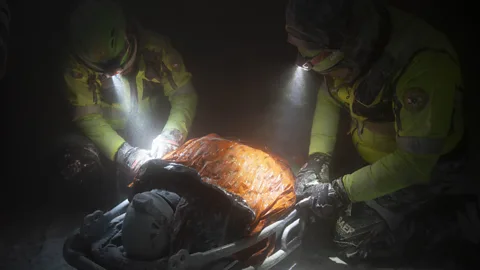

"Here's the scenario: you're on foot, there are three victims, they're climbers, injured by rockfall," an instructor calls out to a group of mountain rescuers in orange jackets, yellow helmets, goggles and climbing harnesses. A metal door opens, and snow billows out. The rescuers switch on their head torches and rush through the door with their stretcher, into a huge, dark room fitted out to feel like a windswept mountain at night.

The staged rescue is part of a training session at the Institute of Mountain Emergency Medicine at Eurac Research, a research centre in Bolzano, Italy. Scientists here are testing new ways to keep people safe in the mountains. To do that, they conduct experiments inside a giant box called an "extreme climate simulator", where the temperature, air pressure, light levels, and snow and wind conditions can be adjusted to simulate any weather and altitude.

For emergency medicine specialists from all over Italy, the simulator also offers a new way to train for dangerous missions, from cave rescues, to helping trapped climbers safely off a cliff face.

"Some of the most complex rescues are those involving climbers, when they are on a rock wall with just a big void below them," says Simona Berteletti, the director of the medical school of Italy's Mountain and Cave Rescue Service, which undertakes more than 12,000 missions a year. Like in many hot-spots for outdoor pursuits around the world, that number is rising as outdoor tourism is booming. The operations can put the helpers themselves at risk: a study of injuries suffered by Italian search and rescue specialists found that 41% of them happened during the missions, and 59% during training events.

Eurac Research/Andrea De Giovanni

Eurac Research/Andrea De Giovanni"Since the pandemic, we've seen a huge increase in the number of people visiting the mountains, including people who are very inexperienced," says Giacomo Strapazzon, the head of the Institute of Mountain Emergency Medicine. "So the number of missions is continually growing. And we also see the rescuers themselves having accidents, be it during training, or during the mission itself."

Inside, the climate simulator – which goes by the name "terraXcube" – essentially feels like a giant, and very noisy, fridge. Loud ventilators blow snow across the floor. On one side is scaffolding, simulating a rock wall where three climbers – or rather, people pretending to be climbers, along with some fake limbs – are entangled in their ropes. One is hanging from the wall; another is trapped on a high ledge; a third has fallen and is lying at the bottom of the wall. It's -17C (1F). As soon as one of the climbers is safely brought down from the wall, the rescuers are told that he is now suffering a cardiac arrest.

"Here we can safely practice treating people in the most extreme conditions, in the cold, and in darkness," says Berteletti, standing outside the chamber. The rescuers still also practice outdoors, but use the simulator to master extreme scenarios and complex techniques in safety, thereby reducing the overall risk of injury during training. "And if anyone gets unwell during the exercise, they can just leave the box," she says. "Whereas if you're doing a training session 4,000m [13,000ft] above sea level, on a glacier, and someone feels unwell – that's a long way down."

Italian Mountain and Cave Rescue Service

Italian Mountain and Cave Rescue ServiceBerteletti's usual missions are on Monte Rosa, a 4,600m (15,000ft) mountain on the border between Italy and Switzerland, which is home to Europe's highest refuge. She says that accidents there include people falling into crevasses on the glacier, climbers falling off the ridges, and altitude-related illnesses. Italy is also home to many caves, which present a special set of challenges.

Nodding at a passing cave rescue specialist, known as a "speleo" (short for speleological rescue), Berteletti says cave missions are very complex, and completely different from the others. "They can be extremely long and take days, even weeks, going 1,000m [3,300ft] deep. Sometimes they have to set up entire hospital tents underground."

During breaktime, the participants, who are rescue specialists from all over Italy, share the most common reasons people can get into trouble, such as slippery footwear, and leaving trails. But seemingly harmless activities can also be surprisingly risky. "We often rescue mushroom pickers," says Oscar Santunione, from the Piste Cimone rescue service in the Emilia-Romagna region. "Our area is famous for mushrooms, and there are a lot more people these days who come foraging for them. They underestimate the terrain, which can drop off very suddenly."

Climate change and avalanches

Climate change is also increasing certain outdoor risks. The European Alps have warmed twice as much as the global average, and a 2024 analysis by researchers in Switzerland has found that the change is altering certain environmental hazards. It has for example led to an increase in rockfall in the high mountains due to thawing glaciers and permafrost, which previously acted as a kind of glue for the rocks. (Read more about how climate change is changing the Alps by causing high-altitude permafrost to thaw.)

There has also been "a shift towards avalanches with more wet snow and fewer powder clouds", due to rising temperatures, according to the study.

Italian Mountain and Cave Rescue Service

Italian Mountain and Cave Rescue ServiceRescue techniques can make a big difference in how well we cope with hazards, research suggests. For example, the survival rate for avalanche accidents in Switzerland has risen by 10% between 1981 and 2020, while rescue times have become faster over that period, according to a study by Eurac Research and WSL, the Swiss Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research. A rise in preventive measures such as avalanche warning services, training for ski tourers, better search-and-rescue techniques, and improved emergency medical care, have all helped boost the survival rate, the study's authors say.

However, rescuers now have less time to get someone out of an avalanche alive: the critical window, where survival probability exceeds 90%, has shortened from 15 to just 10 minutes after being buried by the snow, the study suggests. Strapazzon says this could be linked to severe injuries, or the wetter, denser snow, which makes it harder to breathe – but that more research is needed to study those potential links.

How to ski safely

"I ski a lot," says Giacomo Strapazzon, with a smile. But as a specialist in emergency medicine, he's also especially aware of the risk of skiing accidents. Data from different countries suggests that safety gear such as helmets helps protect people. However, skiers, including children, still face many dangers that can cause severe injury and death – such as falls and collisions, especially where slopes intersect. Risk factors include skiing too fast, which results in more severe injuries. Injury prevention programmes, which aim to raise awareness of injury risks and how to avoid them, can help bring down the injury rate.

Strapazzon's main advice: Don't ski too fast. Observe the rules of the piste you're on. And don't drink alcohol and ski. If we all observed these simple steps, he says, there'd be a lot fewer accidents.

Strapazzon emphasises the importance of precautions, such as having avalanche safety training and carrying an avalanche safety kit when ski touring. This applies even if you are going with a guide, he says. "If the guide is also buried by the avalanche, what are you going to do?"

Ski touring, also known as backcountry skiing, involves going into wilder areas away from groomed pistes. While it is becoming more popular, it's considered high-risk especially because of the risk of avalanches.

Other risks are triggered by outdoor trends, the rescuers say. "One thing that's changed a lot is the number of accidents involving cycling," says Berteletti. "These days we see a lot of people on e-bikes, who use them to get up the mountain easily, without any training, but then don't know how to get back down, which is more difficult. Before, we didn't really have that problem, because only very experienced, strong cyclists made it up the mountain in the first place."

People unfamiliar with the mountains may also simply underestimate its capricious weather, Strapazzon says. Pointing at the sunny autumn sky outside the window, he says this is exactly the kind of day that can be dangerous. "On a sunny autumn day like this, people climb up a Via Ferrata [a type of climbing route with steel cables and ladders], then they arrive at the top, there's snow and ice, and they don't have crampons or ice picks, because they didn't expect this," he says. "And it gets dark earlier, so they're surprised by the dark."

While rescue missions mostly end well, the sheer volume of operations can put a strain on the helpers, who are usually unpaid volunteers. In the US, the increase in rescue calls is putting overstretched helpers at the risk of burning out, according to a 2022 study of America's busiest search and rescue services, which are found in Colorado.

Eurac Research/Andrea De Giovanni

Eurac Research/Andrea De GiovanniA safer exit

Anyone trapped on a mountain may greet the sight of a nearing helicopter with huge relief – but unfortunately, its arrival does not mean the danger is truly over. Helicopters can crash, and operations hoisting people up, can go wrong. The pilot and others in the helicopter may also struggle with altitude.

Marika Falla, a neurologist and senior researcher at Eurac Research, used the extreme climate simulator to test the impact of altitude on the cognitive function of emergency providers.

"We found that at 5,000m (16,400ft), their reaction time was slower," says Falla. A helicopter may fly at that altitude on rescue missions, she explains, and both the pilot and any emergency providers on board could be affected. Providing everyone on board with oxygen bottles could help prevent these problems with attention and reaction time, a separate study by Falla and her colleagues suggests. They found that oxygen supplementation improved cognitive performance during exposure to 4,000m (13,100ft) altitude.

Italian Mountain and Cave Rescue Service

Italian Mountain and Cave Rescue ServiceIn the future, drones may also be an alternative to helicopters in some cases, says Strapazzon, and could carry equipment such as defibrillators.

"Helicopters can't always fly," because of the weather, and some terrain such as a narrow gorge may not be accessible by helicopter, he explains. "A drone can fly where a helicopter can't – and it gets there more quickly, because it can be kept packed and ready."

Strapazzon emphasises that being aware of the risks is helpful when enjoying the mountains – but also, that it shouldn't put people off them. "Being in the mountains comes with a certain risk, but if you stayed away, you'd miss out on a beautiful experience," he says.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.