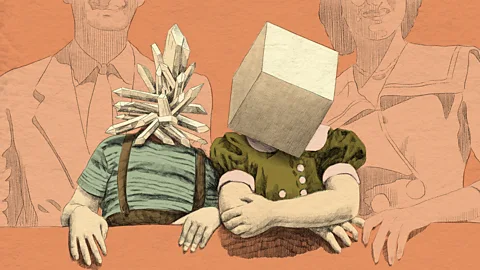

'Eldest daughter syndrome' to the rebellious youngest sibling: Does your birth order shape your personality?

The question of whether siblings' birth order shapes their personality has puzzled families and psychologists for years. But the evidence isn't as straightforward as you might think.

As the eldest daughter of two, I often identify with the traits stereotypically associated with being the oldest sibling: responsible, conscientious, a perfectionist. My mum is an eldest daughter, too, and also shares those traits. My younger sister, on the other hand, is a bit more carefree – even though she and I grew up in the same household with the same parents, and are close, our personalities are quite different.

I wondered whether that difference could be due to our birth order – is there any science to the idea that being the oldest, the youngest, or an only child, shapes who we are, and how we navigate the world?

A century-long mystery

Despite fascinating the scientific community and public for more than 100 years, the question of whether our birth order amongst siblings shapes our personalities is very much still up for debate.

Historically, research has produced inconsistent findings. There are several reasons why this is, though to put it simply: it's hard to measure. Rodica Damian, an associate professor in psychology at the University of Houston, Texas, in the US, explains that previous studies have often included small sample sizes. In addition, since personality tests are often self-reported, they may be affected by bias.

"The Big Five"

The five-factor model of personality is used to determine general personality structure. Psychologists researching birth order measure siblings on the following traits:

• Extraversion (or introversion)

• Agreeableness

• Conscientiousness (or intelligence)

• Neuroticism (or emotional stability)

• Openness to experience

Recent studies point out that a number of confounding variables can make it hard to investigate if birth order is systematic, meaning that it affects every person in the same way. The total number of siblings may be a factor, for example: one would expect the overall dynamics to be different in a family with two siblings compared to a family with seven siblings. Being the eldest or youngest child in these differently-sized families might be a very different experience, and not directly comparable.

Family size and the experience of being a child in any given family may in turn be entangled with many other factors, such as a family's socioeconomic status (wealthier families with higher socioeconomic status tend to have fewer children, for example). And then there is a person's age and gender, which could influence their experience within the family and beyond.

Within this context, researchers have not been able to conclude that birth order has any consistent, universal impacts on our personalities. But that doesn't mean birth order is irrelevant. It could play a role within certain families, or cultures.

"I think people have a lot of beliefs that are kind of outdated, or that were never well supported in the first place," says Julia Rohrer, a personality researcher at Leipzig University in Germany. "For example, the 'eldest daughter syndrome' thing is a big one – of course, women often still have different roles and are expected to provide more care. And then, first-borns are expected to take care of younger siblings," she says. "For some women, this might perfectly match their experience but for others it doesn't because every family is different." In other words, not every eldest daughter will be responsible and caring – but for some, the idea of an "eldest daughter syndrome" may ring true because they really did grow up having to look after their younger siblings and feel that this experience shaped them.

Rohrer and her colleagues have found that birth order "does not have a lasting effect on broad personality traits" after examining three large datasets from surveys in the UK, US and Germany, each comprising data from several thousand people. However, the study did confirm previous findings on the impact of birth order on one specific trait: intelligence.

Intelligence is a complex phenomenon and the study only measures it in the form of performance in intelligence tests, and self-reported intellect. "We confirmed the effect that firstborns score higher on objectively measured intelligence and additionally found a similar effect on self-reported intellect," Rohrer and her colleagues wrote in the study. Previous research had documented that performances in intelligence tests "decline slightly from firstborns to later-borns".

As for birth order and other personality traits, Rohrer says reflecting on one's experience can still be meaningful, even if there is no universal pattern: "It does provide a label where you can find other people who grew up in a similar situation, and you can exchange experiences and so on," she says of terms such as "eldest daughter syndrome". There is nothing wrong with framing your experience that way, "as long as you don't assume that this experience is universal," she says.

Damian echoes this: "While we don't find differences in personality that are systematic, that doesn't mean that there aren't social processes within each family or within each culture that can lead to different outcomes based on birth order."

For example, the UK has a historically (male-preferring) primogeniture culture, meaning the eldest child would be the first in line to inherit family wealth, estate or titles. Only in 2013, with the passing of the Succession to the Crown Act did primogeniture within the monarchy end, removing the power of a male heir to displace an elder daughter in their right to the Crown. The idea of primogeniture is surprisingly widespread and persistent: in Succession, the HBO satirical comedy-drama, about a family's fight to take over a media empire, one character shouts "I'm the eldest boy!" in the finale. He believes his birth position should give him the right to take over his father's position of CEO. (He is actually the second-eldest son, but we won't get into that).

"If the social practice is based on birth order, then yes, birth order will impact your outcomes," says Damian.

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontAge is just a number?

Age-related experiences can easily be mistaken for a personality trait or behaviour influenced by birth order, the researchers explain. Take the older, "responsible" sibling as an example: "As people grow older, they become more responsible, more self-controlled. So, the firstborn is always going to be older than the later born, and as you observe your children grow, the firstborn will always be more responsible," says Damian.

"Another thing is that people become more self-conscious as they grow older," she adds. "So the second-born might appear more sociable and less neurotic, because a 10-year-old is much more happy and full of themselves… compared to the 14-year-old, who's freaking out about everything. That's because they have different challenges."

Factors such as children's friendship circles also matter. Multiple studies suggest a link between delinquent peers and delinquent behaviour, for example, so an older child could be more of a rule-breaker depending on the people with whom they surround themselves.

Smart siblings

As aforementioned, one consistent finding that crops up in birth order research is the link between birth order and intelligence, with firstborns averaging slightly higher in intellect-related traits than younger-borns. "[The intelligence link] mostly shows up in verbal intelligence test results, and it has a very small effect," says Damian. Also, "if you took a test twice, you'll probably score depending on the day or mood, [or] whatever you ate that morning, [or] how long you slept."

It may also be explained by cognitive stimulation in the early years of life. Damian points out that the more adults per child you have in a family, the more exposed they are to mature language and vocabulary. But when there are more siblings born into a family, levels of intellectual stimulation might decrease. "So it's not so much that they're genetically smarter or that they have more potential – it's more that they translate into a higher verbal IQ score on the test which could be due to knowing more words, because more adults versus children spoke to them," she says. "With two children, maybe some of that reading time is taken by managing sibling interactions where the verbal input is a little bit less elevated." There are also suggestions that as older siblings tutor younger siblings, or explain things to them, they use "more cognitive resources".

Interestingly, these patterns of intelligence aren't replicated globally. Data from developing countries differs to data from developed countries, for example. In Indonesia, later-born siblings are likely to have better educational opportunities than their older siblings, potentially due to financial constraints, easing only when older siblings begin contributing to family income.

According to Damian and her colleague, birth order has "negligible effects" on careers, too. In the past, there an idea prevalent among scientists was that the older sibling would enter a more academic or scientific career, and the younger a more creative one. But Damian found the opposite: in her longitudinal study, which looked at a sample of US high students in 1960 and then the same participants 60 years later, first-borns ended up in more creative careers.

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel Lafont'Selfish' only children?

Only children often face the stereotype of being more selfish than children born with siblings, supposedly because they do not have to compete for a parents' attention. Recent studies, however, have shown that this is not the case, and that growing up without siblings does not lead to increased selfishness or narcissism. Other research suggests that the social behaviours of only children compared to children with siblings are not large or pervasive, and "may grow smaller with age".

Birth order research has typically not included only children on the grounds that they cannot be fairly compared to children who have grown up with siblings. However, it is possible to compare the personality traits of siblings and only children, according to a 2025 paper by Michael Ashton, a professor of psychology at Brock University, Canada, and Kibeom Lee, a professor of psychology at the University of Calgary, Canada.

Their study presented some new and fascinating results. It examined the association between personality, birth order, and number of siblings, in 700,000 adults online in one sample and more than 70,000 in another, separate sample. Middle-born and last-born siblings averaged higher on the "Honesty-Humility" and "Agreeableness" scales than first-born siblings. "Honesty-Humility" measures how honest and humble a person is, meaning, a high-scoring person is unlikely to manipulate others, break rules, or feel entitled. A low-scoring person may be more inclined to break rules and may feel a strong sense of self-importance. On the agreeableness scale, a high-scoring person tends to be forgiving, lenient in judging others, even-tempered and willing to compromise, while a low-scoring person may hold grudges, be stubborn, be quick to feel anger, and be critical of others.

"These differences were quite small in size, particularly when the comparisons involve people from families having the same number of children," Ashton and Lee say in an email. "In contrast, the differences in these dimensions between persons from a one-child family (i.e., only children) and persons from a six-or-more-child family were considerably larger, somewhere between the sizes that social scientists would call 'small' and 'medium'."

So, I ask, is the influence of birth order just a zombie theory – a concept that is wrong but which refuses to die? Rohrer disagrees. "I'm not sure whether I would call it a zombie theory," she says. "From the scientific perspective, I think the literature is progressing quite productively."

So we may, one day, have a clearer answer as to what it means to be an eldest daughter. Until then, I'll keep letting my younger sister believe I'm inherently smarter than her.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.