'My GP told me to get moving after I was paralysed'

BBC

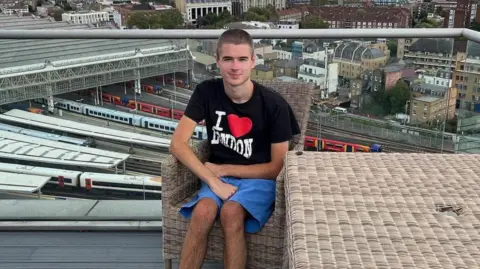

BBCA man who was left unable to walk or talk by a neurological disorder has called for greater understanding of his condition after he was told to "get moving" by a GP.

Liam Virgo, 22, was 13 when he was diagnosed with functional neurological disorder (FND), which affects how the brain sends and receives information to and from the body.

He was left bedbound for three years by the condition, but is now making a slow recovery and learning to walk again.

Mr Virgo said his experience had shown him how little awareness there was about the condition, among both the public and medical professionals, and he hopes his story will help secure more understanding and support for future sufferers.

"My FND paralysed me - I felt trapped inside my own body," he said.

"There's a lot of misunderstanding about what FND is. In the past there have been people who have worked with me who don't understand it.

"Not many people know what it is. They might have heard of it, but they don't know how it affects you."

Mr Virgo, from Annesley in Nottinghamshire, first developed symptoms when he was 12 and was subsequently left unable to walk for five years, was bedbound for three and lost his ability to speak for a year.

Supplied

SuppliedThe condition does not show up on scans and there is no medical treatment for its symptoms.

Even after his diagnosis, Mr Virgo said his symptoms were sometimes mislabelled by health professionals as other conditions such as autism and psychosis.

And others thought he was "pretending" when he was "doubled over in pain", he said.

"We were on the phone when my GP said I needed to get moving. How could I get moving when I can't walk?" he said.

'Imagining their condition'

Sumeet Singhal, a consultant neurologist at the Queen's Medical Centre in Nottingham, said the lack of understanding around the condition needed to change.

"For something so common and that affects so many young people - the fact that it's still not so well known, the fact that most doctors still don't really have a very good understanding of it - it's something we need to focus on," Dr Singhal said.

"In most places it's not even taught in medical school which is something that needs to change."

Dr Singhal said FND could affect neurological function without causing structural damage to the brain or nerves, which could sometimes "confuse people into thinking it's somehow less real or serious than other conditions we see".

He added: "Probably most people will tell you that at some stage they've been told they're imagining their condition or even that people might think they're putting their symptoms on."

Supplied

SuppliedDr Singhal said there had been a number of different theories on how the condition starts.

"One of the prevalent theories is that it's due to this process called disassociation, which is when the brain shuts itself down," he added.

"It might be overwhelmed, it may be exhausted, it may be triggered by pain. And essentially then, our brains sort of disconnect from parts of our body."

Dr Singhal added anyone could be affected by FND, but that there was an "increased association" with things like early-life trauma and neurodiversity.

"There are definitely links but we still don't quite understand how it all fits together to explain exactly the diagnosis and why exactly they develop it," he said.

Follow BBC Nottingham on Facebook, on X, or on Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected] or via WhatsApp on 0808 100 2210.