What's next for WW2 site now storing nuclear waste?

NWS

NWSOn the doorstep of a small village, there is a site which looks a little like an industrial estate, apart from its tall fences topped with barbed wire and huge gates. It's not the kind of place you can just wander into - tonnes and tonnes of radioactive waste is stored here. The BBC was allowed to see what happens behind the gates of the UK's only Low Level Waste Repository (LLWR).

On Cumbria's west coast, just outside the village of Drigg, an explosives factory that shipped about 400 tonnes of TNT per week during World War Two once stood.

It became a nuclear store for low level radioactive waste in 1959 and is expected to continue operating until 2135.

This week, a major operation is starting here to cover and secure an area the size of about 56,000 football pitches full of radioactive waste.

Site manager Mike Pigott says it could survive extreme scenarios, including the breakdown of society.

"We almost have to assume that future generations potentially could not intervene in certain scenarios, so we need to make sure it's robust to protect people and the environment multiple generations into the future - potentially thousands of years," he says.

NWS

NWSThe waste arriving here is anything from PPE used around radioactive materials on nuclear sites, to tools used in nuclear operations.

But while nearby Sellafield is the main client, waste also arrives from nuclear submarine sites such as Devonport in Plymouth, the oil and gas extraction sector where naturally occurring radioactive materials are found, and even materials used for certain cancer treatments and smoke detectors.

Hills of nuclear waste

When nuclear waste was first stored at the LLWR, trenches were dug out and filled with radioactive waste, which was then covered in a similar way to a landfill site.

"For us it looks like an innocuous grass hill and that's effectively what it is, but a few metres beneath our feet is in the region of half a million metres cubed (17.6 million cubic feet) of radioactive waste that's safely and permanently disposed of," says Mr Pigott.

NWS

NWSStanding of top of that grassy hill, we can see how things changed since 1988, with the creation of what the LLWR refers to as "vault eight".

It looks like a huge dug-out concrete car park, with rows and rows of shipping containers weighing up to 35 tonnes each.

There is a ramp going down to give access to the mammoth forklift trucks which stack four to six containers on top of each other.

'Manage expectations'

Vault eight has a capacity of 10,000 containers and is now pretty much full.

The LLWR is starting to receive deliveries of aggregate material to cover it up to secure the waste, a process known as capping.

The hill-like membrane covering the old waste will also be replaced, meaning it will become up to 50ft (15m) taller.

Mr Pigott says because of the proximity of houses, it is important for them to manage any potential disruption to the community.

NWS

NWSThey are expecting multiple deliveries per week, with 20 wagons per delivery bringing 1,500 tonnes of aggregates into the site.

"It's significant volumes," he says.

"For us the immediate thing...is starting to manage the expectations from what has been a relatively quiet site in this area."

Sound barriers have been installed to reduce noise from what Mr Pigott says will effectively become a building site, and the railway deliveries have been planned to also minimise the impact.

Explosive material found

But this new stage of work - expected to take about a decade - is also throwing up other problems as more of the WW2 legacy has to be managed.

"From my personal perspective as site director for the LLWR site, it's really important to understand what I have inherited from that Royal Ordnance Factory," Mr Pigott says.

NWS

NWS"We're now exploring bits of site - and actually excavating and constructing in bits of sites - that we've not done for 60 or 70 years in some cases."

During one operation, they discovered some discolouration in the water beneath the ground, with tests revealing the water contained picric acid, a material highly explosive when dry, used as part of the TNT production.

Transparency questions

Last year, LLWR was found to have breached its environmental permit by the Environment Agency (EA), because of delays with the capping processes.

The information was obtained through a Freedom of Information request by the BBC, after several pushbacks to obtain the documents from the relevant parties.

Martin Walkingshaw, chief operating officer for Nuclear Waste Services (NWS) which looks after the LLWR site, says he is "disappointed" to hear it was difficult to obtain the information and adds NWS is committed to being open and transparent.

NWS

NWSThe company publishes a regular newsletter, attends regular public parish council meetings and stakeholder groups, where the community is able to go along and hold the organisation to account, he says.

He adds: "You should never have to resort to an FOI to get information out of us."

He also acknowledges NWS was behind on several milestones, which is the reason why the EA deemed its permit to have been breached, but says it is in the process of agreeing new deadlines for the work to be completed.

He adds while delay was "always regrettable", the pace of work had to be consistent with managing risks and hazards.

'No GDF is unthinkable'

Up to 150 people work on site at the LLWR, which is wedged between a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) off the Irish Sea, complete with natterjack toads and great crested newts, and the rural hamlet of Drigg.

However, about 1,000 work for NWS, which is also behind the search for an area to host a geological disposal facility (GDF) for high level nuclear waste.

Mr Walkingshaw believes it is "unthinkable" the UK will stop using nuclear technology and a GDF is essential to deal with the waste coming from it.

As well as supporters for the project, there are also critics.

There are concerns around the environmental impacts of a GDF, its safety and transparency around the project.

NWS

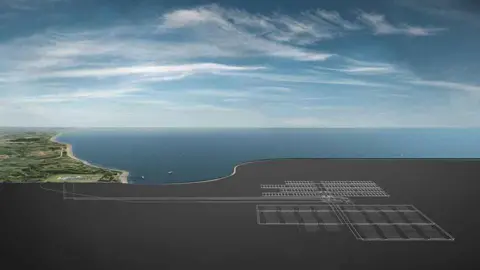

NWSA GDF has been on the cards for decades and previous work to identify suitable areas had looked at an inland option.

However, Mr Walkingshaw is keen to highlight this project is different, as the high level waste would be stored in a facility about 12km (7.4 miles) offshore.

Three sites are being considered - two in Cumbria and one in Lincolnshire - and Mr Walkinshaw says it is not just the geology that has to be right, but the community also needs to be willing to have it on their doorstep.

"Every democratically elected government in this country pretty much since the second World War has had civil nuclear power and an independent nuclear deterrent as part of the manifesto that it's been elected on," he says.

"So I think, to me, a GDF is non-negotiable, we need geological disposal to close the loop on what otherwise become very long-term liabilities."

Follow BBC Cumbria on X, Facebook, Nextdoor and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected].