How Spitalfields reflects the ever-changing face of London

Getty Images

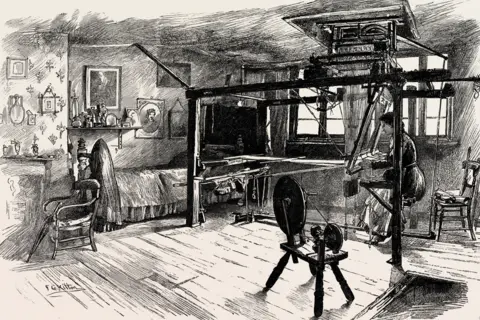

Getty ImagesLight shines brightly into the bare first-floor room of 113 Redchurch Street in Spitalfields, east London.

"You'd have had silk weavers working here, and weavers on the next floor, and weavers on the next floor above," explains architect Chris Dyson, who worked on the restoration of the Grade II-listed building and its counterpart next door.

"They often lived and worked in these spaces but it would be a workroom, really, by day and they would weave as long as the light would allow them to do so."

The two properties, both built in 1735, hark back to a time when the area was very different.

The late 1600s and 1700s saw about 200,000 Huguenots flee France in the face of the persecution of Protestants.

Some 50,000 of them arrived in England, many settling in Spitalfields, bringing with them skills like silk-weaving.

The influx was such that a huge part of London's East End became known as "weaver town" as it transformed into a centre for the trade, led by migrants from across the English Channel.

"The first couple of generations, people spoke French and it became known as quite a French area," says Julia Kuznecow, a guide of more than 20 years, who organises walks around Spitalfields.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Nevertheless, within a few generations that French influence began to diminish.

"They integrated so quickly... and many of them changed their names because of the constant wars with France and the constant troubles," Ms Kuznecow says.

A large building on the corner of Brick Lane and Fournier Street reflects this.

Built in 1743, it started life as a French Protestant church serving the Huguenot population, but was shut in 1809 due to a drastic decline in attendance.

"That lifespan is about average [for Huguenot churches]. They probably limped on towards the end to try desperately to keep it open and realising that they couldn't because there really wasn't anybody to use it any more," explains Ms Kuznecow.

By the end of the 19th Century, that same building reflected how the population of Spitalfields had changed again, becoming a synagogue to serve the growing Jewish population.

While Jewish people had already been settling in the area, pogroms across Russia and neighbouring countries following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 saw more people arrive in an already-crowded part of town.

Many of those found employment in the textile industry and of those who arrived in London, some 60% ended up working in the fashion industry.

Hints of the area's Jewish past can still be found near the homes once used by weavers.

Along Princelet Street, Ms Kuznecow points to a house which still has a detail on the door that would have been common in other properties locally.

"Every house in a Jewish town has a mezuzah on the door, which is like a little tube with a little Torah scroll inside and when you come through, you touch it."

Further down the road is a house with a peeling pink front, which was the childhood home of songwriter and Oliver! composer Lionel Bart, whose father was a tailor.

"His [Lionel's] name was Beglieter, and he took the name Bart from Bart's hospital. It would have obviously been a very Jewish area when he was growing up," says Ms Kuznecow.

Like the Huguenots before them, over time Jewish people dispersed from the area, some of them to the richer suburbs of north London.

The synagogue they used to attend closed down in the 1970s and before long became the Brick Lane Mosque, also known as Brick Lane Jamme Masjid, reflecting the arrival of Bangladeshi immigrants.

As was the case with the Jewish incomers, Bengalis had already been settling in the area, but political upheaval at home from the middle of the 20th Century saw a significant increase in the number of people arriving.

"They carried on the textile stuff the Jewish people were in a lot," says Ms Kuznecow, "and of course they did a lot of restaurants and cooking".

Brick Lane now boasts numerous Bengali grocers and textile stores - as well as the curry houses the street is today best known for.

In the 2021 census, 20.7% of London's overall population of 8.8 million people described themselves as Asian, Asian British or Asian Welsh - while in the Spitalfields and Banglatown ward 51.8% were recorded as Asian, Asian British and Asian Welsh.

Ms Kuznecow points out that this part of London is continuing to experience change.

"Whereas 10 or 20 years ago, every business was Bangladeshi, now they're not, they're sort of thinning out. So things change and people move on very quickly," she says.

"I suspect if you come here in 100 years' time it will be something completely different again."

This sentiment is echoed by Panikos Panayi, professor of European history at De Montfort University. He says that Spitalfields, like other parts of London, has seen constant demographic change over the centuries.

Prof Panayi, author of Migrant City: A New History of London, explains that before the middle of the 20th Century the most common places from which people came to London were within the British Isles, and from central and Eastern Europe.

"After the Second World War is when it becomes increasingly diverse," he explains, with the likes of the Windrush generation also arriving - while the expansion of the EU in 2004 had its own impact on London's demographics.

"It's in 21st Century where we can probably use the phrase 'superdiverse'," he says.

Prof Panayi believes London's place on the world stage means it will continue to be a "migrant city".

"London is still a phenomenally important city in the global economy so it will attract migration... it'll just come from different parts of the world from what it did before we left the EU in 2021."

Back in Redchurch Street, two buildings that were once homes and workplaces for French and Jewish immigrants - and had until recently been on the verge of disintegration - are set to take a new place in Spitalfields' textiles tradition.

Having been purchased by the Truman Brewery estate, run by the Zeloof family who made their wealth through the clothing industry, they have undergone a £2m restoration project and are set to become the first UK base for Canadian-Egyptian sustainable fashion firm KOTN.

Out on the street, Chris Dyson points to the growing number of high-end clothing shops springing up around the area.

For all that things have changed over time, Spitalfields' centuries-old association with textiles endures, he says.

"They're still keeping the area's connection with fashion."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected]