Migrant deported in chains: 'No-one will go to US illegally now'

BBC

BBCGurpreet Singh was handcuffed, his legs shackled and a chain tied around his waist. He was led on to the tarmac in Texas by US Border Patrol, towards a waiting C-17 military transport aircraft.

It was 3 February and, after a months-long journey, he realised his dream of living in America was over. He was being deported back to India. "It felt like the ground was slipping away from underneath my feet," he said.

Gurpreet, 39, was one of thousands of Indians in recent years to have spent their life savings and crossed continents to enter the US illegally through its southern border, as they sought to escape an unemployment crisis back home.

There are about 725,000 undocumented Indian immigrants in the US, the third largest group behind Mexicans and El Salvadoreans, according to the most recent figures from Pew Research in 2022.

Now Gurpreet has become one of the first undocumented Indians to be sent home since President Donald Trump took office, with a promise to make mass deportations a priority.

Gurpreet intended to make an asylum claim based on threats he said he had received in India, but - in line with an executive order from Trump to turn people away without granting them asylum hearings - he said he was removed without his case ever being considered.

About 3,700 Indians were sent back on charter and commercial flights during President Biden's tenure, but recent images of detainees in chains under the Trump administration have sparked outrage in India.

US Border Patrol released the images in an online video with a bombastic choral soundtrack and the warning: "If you cross illegally, you will be removed."

US Border Force

US Border Force"We sat in handcuffs and shackles for more than 40 hours. Even women were bound the same way. Only the children were free," Gurpreet told the BBC back in India. "We weren't allowed to stand up. If we wanted to use the toilet, we were escorted by US forces, and just one of our handcuffs was taken off."

Opposition parties protested in parliament, saying Indian deportees were given "inhuman and degrading treatment". "There's a lot of talk about how Prime Minister Modi and Mr Trump are good friends. Then why did Mr Modi allow this?" said Priyanka Gandhi Vadra, a key opposition leader.

Gurpreet said: "The Indian government should have said something on our behalf. They should have told the US to carry out the deportation the way it's been done before, without the handcuffs and chains."

An Indian foreign ministry spokesman said the government had raised these concerns with the US, and that as a result, on subsequent flights, women deportees were not handcuffed and shackled.

But on the ground, the intimidating images and President Trump's rhetoric seem to be having the desired effect, at least in the immediate aftermath.

"No-one will try going to the US now through this illegal 'donkey' route while Trump is in power," said Gurpreet.

In the longer term, this could depend on whether there are continued deportations, but for now many of the Indian people-smugglers, locally called "agents", have gone into hiding, fearing raids against them by Indian police.

Gurpreet said Indian authorities demanded the number of the agent he had used when he landed back home, but the smuggler could no longer be reached.

"I don't blame them, though. We were thirsty and went to the well. They didn't come to us," said Gurpreet.

While the official headline figure puts the unemployment rate at only 3.2%, it conceals a more precarious picture for many Indians. Only 22% of workers have regular salaries, the majority are self-employed and nearly a fifth are "unpaid helpers", including women working in family businesses.

"We leave India only because we are compelled to. If I got a job which paid me even 30,000 rupees (£270/$340) a month, my family would get by. I would never have thought of leaving," said Gurpreet, who has a wife, a mother and an 18-month-old baby to look after.

"You can say whatever you want about the economy on paper, but you need to see the reality on the ground. There are no opportunities here for us to work or run a business."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGupreet's trucking company was among the cash-dependent small businesses that were badly hit when the Indian government withdrew 86% of the currency in circulation with four hours notice. He said he didn't get paid by his clients, and had no money to keep the business afloat. Another small business he set up, managing logistics for other companies, also failed because of the Covid lockdown, he said.

He said he tried to get visas to go to Canada and the UK, but his applications were rejected.

Then he took all his savings, sold a plot of land he owned, and borrowed money from relatives to put together 4 million rupees ($45,000/£36,000) to pay a smuggler to organise his journey, Gurpreet told us.

On 28 August 2024, he flew from India to Guyana in South America to start an arduous journey to the US.

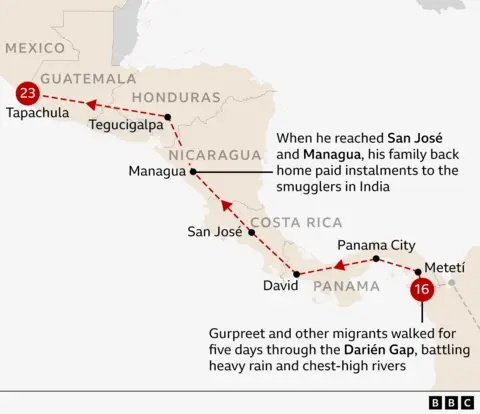

Gurpreet pointed out all the stops he made on a map on his phone. From Guyana he travelled through Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia, mostly by buses and cars, partly by boat, and briefly on a plane - handed from one people-smuggler to another, detained and released by authorities a few times along the way.

From Colombia, smugglers tried to get him a flight to Mexico, so he could avoid crossing the dreaded Darién Gap. But Colombian immigration didn't allow him to board the flight, so he had to make a dangerous trek through the jungle.

A dense expanse of rainforest between Colombia and Panama, the Darién Gap can only be crossed on foot, risking accidents, disease and attacks by criminal gangs. Last year, 50 people died making the crossing.

"I was not scared. I've been a sportsman so I thought I would be OK. But it was the toughest section," said Gurpreet. "We walked for five days through jungles and rivers. In many parts, while wading through the river, the water came up to my chest."

Each group was accompanied by a smuggler - or a "donker" as Gurpreet and other migrants refer to them, a word seemingly derived from the term "donkey route" used for illegal migration journeys.

At night they would pitch tents in the jungle, eat a bit of food they were carrying and try to rest.

"It was raining all the days we were there. We were drenched to our bones," he said. They were guided over three mountains in their first two days. After that, he said they had to follow a route marked out in blue plastic bags tied to trees by the smugglers.

"My feet had begun to feel like lead. My toenails were cracked, and the palms of my hands were peeled off and had thorns in them. Still, we were lucky we didn't encounter any robbers."

When they reached Panama, Gurpreet said he and about 150 others were detained by border officials in a cramped jail-like centre. After 20 days, they were released, he said, and from there it took him more than a month to reach Mexico, passing through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala.

Gurpreet said they waited for nearly a month in Mexico until there was an opportunity to cross the border into the US near San Diego.

"We didn't scale a wall. There is a mountain near it which we climbed over. And there's a razor wire which the donker cut through," he said.

Gurpreet entered the US on 15 January, five days before President Trump took office - believing that he had made it just in time, before the borders became impenetrable and rules became tighter.

Once in San Diego, he surrendered to US Border Patrol, and was then detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

During the Biden administration, illegal or undocumented migrants would appear before an immigration officer who would do a preliminary interview to determine if each person had a case for asylum. While a majority of Indians migrated out of economic necessity, some also left fearing persecution because of their religious or social backgrounds, or their sexual orientation.

If they cleared the interview, they were released, pending a decision on granting asylum from an immigration judge. The process would often take years, but they were allowed to remain in the US in the meantime.

This is what Gurpreet thought would happen to him. He had planned to find work at a grocery store and then to get into trucking, a business he is familiar with.

Instead, less than three weeks after he entered the US, he found himself being led towards that C-17 plane and going back to where he started.

In their small house in Sultanpur Lodhi, a city in the northern state of Punjab, Gurpreet is now trying to find work to repay the money he owes, and fend for his family.

Additional reporting by Aakriti Thapar