Three children drown every day in India's wetlands. But mothers are fighting back

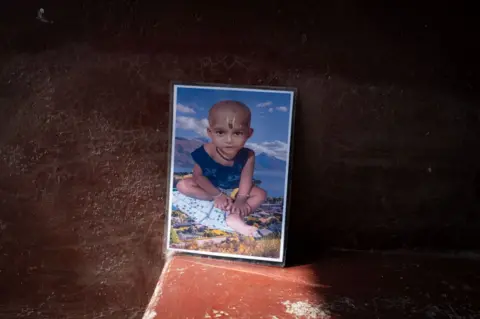

Swastik Pal

Swastik PalMangala Pradhan will never forget the morning she lost her one-year-old son.

It was 16 years ago, in the unforgiving Sundarbans - a vast, harsh delta of 100 islands in India's West Bengal state. Her son Ajit, just beginning to walk, was full of life: frisky, restless, and curious about the world.

That morning, like so many others, the family was busy with their daily chores. Mangala had fed Ajit breakfast and taken him to the kitchen as she cooked. Her husband was out buying vegetables, and her ailing mother-in-law rested in another room.

But little Ajit, always eager to explore, slipped away unnoticed. Mangala shouted for her mother-in-law to watch him, but there was no reply. Minutes later, when she realised how quiet it had become, panic set in.

"Where is my boy? Has anyone seen my boy?" she screamed. Neighbours rushed in to help.

Desperation quickly turned to heartbreak when her brother-in-law found Ajit's tiny body floating in the pond in the courtyard outside their ramshackle home. The little boy had wandered out and slipped into the water - a moment of innocence turned into unthinkable tragedy.

Swastik Pal

Swastik PalToday, Mangala is one of 16 mothers in the area who walk or cycle to two makeshift creches set up by a non-profit where they look after, feed and educate some 40 children, who are dropped off by their parents on way to work. "These mothers are the saviours of children who are not their own," says Sujoy Roy of Child In Need Institute (CINI), which set up the creches.

The need for such care is urgent: countless children continue to drown in this riverine region, which is dotted with ponds and rivers. Every home has a pond used for bathing, washing, and even drawing drinking water.

A 2020 survey by medical research organisation The George Institute and CINI found that nearly three children aged between one and nine years drowned daily in the Sundarbans region. Drownings peaked in July, when the monsoon rains began, and between ten in the morning and two in the afternoon. Most children were unsupervised at that time as caregivers were occupied with chores. Around 65% drowned within 50m of home, and only 6% received care from licensed doctors. Healthcare was in shambles: hospitals were scarce and many public health clinics were defunct.

Swastik Pal

Swastik PalIn response, villagers clung to ancient superstitions to save rescued children. They spun the child's body over an adult's head, chanting invocations. They beat the water with sticks to ward off spirits.

"As a mother, I know the pain of losing a child," Mangala told me. "I don't want any other mother to endure what I did. I want to protect these children from drowning. We live amid so many dangers anyway."

Life in Sundarbans, home to four million people, is a daily struggle.

Tigers, known to attack humans, roam dangerously close to and enter crowded villages where the poor eke out a living, often squatting on land.

People fish, collect honey, and gather crabs under the constant threat of tigers and venomous snakes. From July to October, rivers and ponds swell due to heavy rains, cyclones lash the region, and rampaging waters swallow villages. Climate change is worsening this uncertainty. Nearly 16% of the population here is aged one to nine.

Swastik Pal

Swastik Pal"We've always co-existed with water, unaware of the dangers, until tragedy strikes," says Sujata Das.

Sujata's life was overturned three months ago when her 18-month-old daughter Ambika, drowned in the pond at their joint family home in Kultali.

Her sons were at their coaching classes, some family members had gone to the market, and an elderly aunt was busy working at home. Her husband, who usually works in the southern state of Kerala, was home that day, repairing a fishing net at the nearby trawler. Sujata had gone to fetch water at a local handpump because a promised water connection at her residence had still not materialised.

"Then we found her floating in the pond. It had rained, water had risen. We took her to a local quack, who declared her dead. This tragedy has woken us up to what we should do to prevent such tragedies in the future," says Sujata.

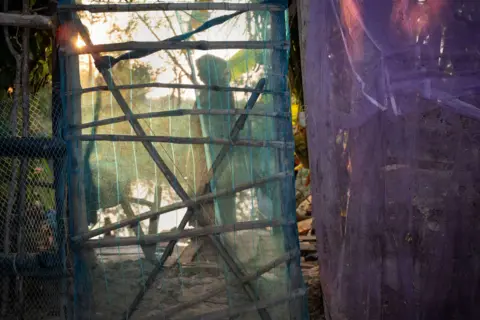

Swastik Pal

Swastik PalSujata, like others in the village, plans to fence her pond with bamboo and nets to prevent children from wandering into the water. She hopes that children who don't know how to swim are taught in village ponds. She wants to encourage neighbours to learn CPR to provide lifesaving aid to rescued drowning children.

"Children don't vote, so the political will to address these issues is often lacking," says Mr Roy. "That's why we're focusing on building local resilience and spreading knowledge." Support from India's top science agency, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), in funding creches and pond fencing has also been crucial.

Over the past two years, around 2,000 villagers have received CPR training. Last July, a villager saved a drowning child by reviving him before he was sent to the hospital. "The real challenge lies in setting up creches and raising awareness among the community," he adds.

Implementing even simple solutions is challenging due to costs and local beliefs.

Swastik Pal

Swastik Pal Swastik Pal

Swastik PalIn the Sundarbans, superstition about angering water deities made it hard to get people to fence their ponds. In neighbouring Bangladesh, where drowning is the leading cause of death for children aged one-four, wooden playpens were introduced in courtyards to keep children safe. However, compliance was low - children disliked them, and villagers often used them for goats and ducks. "This created a false sense of security, and drowning rates slightly increased over three years," says Jagnoor Jagnoor, an injury epidemiologist at the George Institute.

Eventually non-profits set up 2,500 creches in Bangladesh, cutting drowning deaths by 88%. In 2024, the government expanded this to 8,000 centres, benefitting 200,000 children annually. Water-rich Vietnam focused on children aged six-10, using decades of mortality data to develop policies and teach survival skills. This reduced drowning rates, especially among schoolchildren travelling on waterways.

Swastik Pal

Swastik Pal Swastik Pal

Swastik PalDrowning remains a major global issue. In 2021, an estimated 300,000 people drowned - over 30 lives lost every hour, according to the WHO. Nearly half were under 29, and a quarter were under five. India's data is scanty, officially recording around 38,000 drowning deaths in 2022, though the actual number is likely much higher.

In the Sundarbans, the harsh reality is ever-present. For years, children have been either allowed to roam freely or tied with ropes and cloth to prevent wandering. Jingling anklets were used to alert parents to their children's movements, but in this unforgiving, water-surrounded landscape, nothing feels truly safe.

Kakoli Das's six-year-old son walked into an overflowing pond last summer while delivering a piece of paper to a neighbour. Unable to distinguish between the road and the water, Ishan drowned. He had suffered seizures as a child and couldn't learn to swim due to the risk of fever.

"Please, I beg every mother: fence your ponds, learn how to revive children and teach them how to swim. This is about saving lives. We cannot afford to wait," says Kakoli.

For now, the creches serve as a beacon of hope, offering a way to keep children safe from the dangers of water. On a recent afternoon, four-year-old Manik Pal sang a cheerful ditty to remind his friends: I won't go to the pond alone/Unless my parents are with me/I'll learn to swim and stay afloat/And live my life fear-free.