Can we fix our way out of the growing e-waste problem?

Francesco Calo

Francesco Calo"I was a kid of the early 80s, when electronic items were quite expensive and were supposed to last for ages."

Francesco Calo has been learning how to fix his broken TV at a repair event in Tooting, south London.

It might seem a simplistic idea - but repair initiatives such as this one could be part of a solution to the growing amount of electrical and electronic waste.

This waste is becoming a huge problem. The 50 million tonnes of e-waste generated every year will more than double to 110 million tonnes by 2050, making it the fastest growing waste stream in the world, according to the author of a UN report.

Environmental damage

Francesco says the staggering volume of e-waste was one of the main reasons he wanted to get involved in fixing broken gadgets.

He enlisted the help of volunteers at the Restart Project in London. Other, similar projects exist in the UK and around the world.

"This project allows you to reduce waste, extend the life of objects, and it helps people who cannot afford to get rid of items that have developed a fault," he says.

"The issue of electronic waste is overlooked, as electronic items that could be fixed easily go to waste instead, contributing to pollution and increasing the demand for components like rare earth elements, which can have a damaging impact on the environment when sourced."

Dr Ruediger Kuehr, of the United Nations University, which produces the UN's Global E-Waste Monitor, told the BBC that despite having ambitious collection targets in place, "world-wide collections are stagnating or even decreasing".

The UN's next Global E-Waste Monitor is due to be published in April, but with only 41 countries producing official e-waste statistics, the fate of the majority of the waste is "simply unknown", according to Prof Ian Williams of the University of Southampton.

"In countries where there is no national e-waste legislation in place, e-waste is likely treated as other or general waste. This is either land-filled or recycled, along with other metal or plastic wastes," he says.

But e-waste from discarded electrical and electronic products is only part of the problem. A significant contributor to e-waste is the release of toxins from mining and manufacturing.

The rare earth elements being mined are currently crucial components in high-tech electronics, but they are hazardous to extract.

"There is the high risk that the pollutants are not taken care of properly, or they are taken care of by an informal sector and recycled without properly protecting the workers, while emitting the toxins contained in e-waste," Prof Williams says.

Getty Images

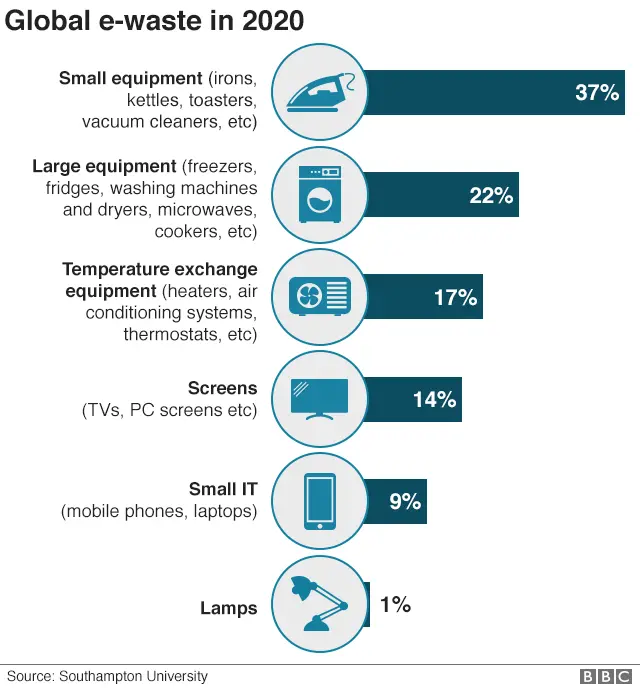

Getty ImagesBy far the biggest contributors to the level of e-waste are household appliances such as irons, vacuum cleaners, washing machines and fridges.

But the rapidly-growing "Internet of things" - internet-connected gadgets - is expected to generate e-waste at a faster rate, as connectivity becomes embedded into everyday items.

There are rules on the management of e-waste. Sellers of electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) within the European Union must provide ways for customers to dispose of their old household device when they sell them a new version of the same product.

And in October 2019, the EU adopted new Right to Repair standards, which means that from 2021 firms will have to make appliances longer-lasting, and will have to supply spare parts for machines for up to 10 years.

The UK government has pledged to "match and even exceed EU eco product regulations" post-Brexit.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSeveral high-profile electronics companies have faced criticism over a lack of availability of spare parts or upgrades, or alleged built-in obsolescence.

In 2017, Apple admitted that it had deliberately slowed down some models of the iPhone as they aged. Customers had suspected this was to encourage people to upgrade, although Apple said it was to prolong the life of customers' devices. In 2018, the company introduced its Daisy robot, used to disassemble iPhones to recover and recycle minerals.

In November 2019, owners of Sonos products criticised the speaker manufacturer for no longer issuing software updates for some of its older models. Affected customers were offered discounts on newer devices in return for recycling their existing product.

Increasingly, investors are only looking at companies that are committed to helping create a cleaner global economy.

Amanda O'Toole, a fund manager at AXA Investment Managers, says that e-waste is "a significant and growing issue".

"We're starting to see companies that, I think, are very mindful of their reputation investing quite heavily here. They recognise the reputational damage of not doing so."

Mark Phillips

Mark PhillipsBut some consumers are taking matters into their own hands - literally. And they don't want new devices.

Back at the Restart Project in London - part of a wider repair movement of community based projects around the world - Francesco's succeeded in repairing his TV screen at the cost of "a few pennies" for a new diode, and the help of one of the volunteers. He tells the BBC he is thinking of becoming a volunteer fixer in the future.

"I love the idea of watching and learning to fix, rather than simply having your item fixed.

"I always try to extend the lease of life of the electronic items I own... by using old mobile phones as music players, or old tablets as digital frames."

Francesco's may only be one fix, but Prof Williams thinks this type of action plays a small, but important, role in tackling what he calls the e-waste "tsunami".

"I think that the repair cafes, the reuse clubs, and people who are trying to prolong the life of electronic equipment - they definitely have a role," he says.

"But the truth is that one in five people - at best - are going to be motivated to do that, so for the remaining four out of five, we need to put systems in place that are convenient, that match their lifestyles and enable us to get the electronic equipment back... into the next item."