No deal in Hungary university stand-off

Reuters

ReutersThe stand-off over the future of a university in Hungary, which became a symbolic international power struggle, shows no sign of being resolved.

The Central European University in Budapest claimed that changes to higher-education laws would force it to shut down - with accusations that it was being attacked for its liberal politics and because it was founded by George Soros, the financier frequently criticised by Hungary's ruling party.

An agreement appeared to have been reached with the Hungarian government after negotiations in the United States, which would have allowed the university to continue.

But speaking in London, a spokesman for Hungary's prime minister indicated that there was still no deal.

Reuters

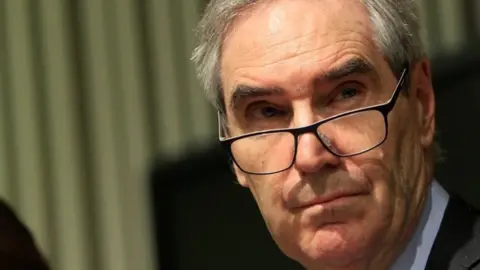

Reuters"They don't come up to the standards, according to our interpretation of what is required by all universities operating in Hungary," said Zoltan Kovacs, spokesman for Viktor Orban.

Mr Kovacs said that the CEU was "enjoying privileges that no other university in the Hungarian system was enjoying".

On whether the deal reached in New York would be implemented, Mr Kovacs said: "If they come up to those standards we'll see."

A spokeswoman for the university, accredited in both the US and Hungary, said that it was already in "full compliance".

"We await the signature of the Hungarian government on the agreement negotiated and agreed upon by both the Hungarian government and the office of the governor of New York state."

Other

OtherThe Hungarian authorities have faced criticism over the CEU dispute from the US government, senior members of the European Commission and leading universities, including Harvard, Yale and Oxford.

The university's president, Michael Ignatieff, said that this was a "line in the sand" and would be the first time since World War Two that a European democracy had forced a university to close.

But Mr Kovacs, speaking at the Hungarian embassy in London, gave no indication that the dispute was about to be settled.

He accused Mr Soros, who has been targeted by a Hungarian government campaign, of "developing an alternative version of democracy" by funding campaign groups and institutions.

Hungary is preparing for an election next month - and it is likely to be seen as another testing ground for populism against more establishment politics.

The prime minister, Mr Orban, has pursued a message of social conservatism, focusing on family, national identity and warning against a "post-Christian" culture.

Reuters

ReutersThis has been blended with messages against globalisation and elites and promises that "those who work more, earn more".

But the most strident arguments have been about immigration - and repeated warnings that Europe's identity was under threat from mass migration.

Mr Kovacs repeated these arguments in unambiguous terms.

Migration was not good or beneficial - and it was a mistake to think it could not be stopped, said the prime minister's official spokesman.

Setting out the terms for the election ahead, and possible future tussles with European institutions, he said that Hungary would not allow "parallel societies" within its borders.

"Nobody thinks of the consequences if Africa starts moving towards Europe," he added.