Why the NHS is struggling like never before

Lives are being put at risk with record long waits in A&E units and 999 calls taking hours to be reached. The causes of this go beyond Covid - and with winter coming it looks set to get worse.

Natalie Quinn's parents were active and enjoying life when the pandemic hit.

Although her father, Jimmy, had been diagnosed with dementia, he was still driving, playing golf and attending groups organised by the Alzheimer's Society. But lockdown hit them hard.

"All my dad's activities stopped and he went downhill quickly," Ms Quinn, 54, says.

"My mum was looking after him, but it took its toll. She had to go into hospital and he went into a care home.

"It was meant to be temporary - but, of course, we couldn't see him. He deteriorated and never came out."

By February, Jimmy, 75, was dead.

Natalie's mother's health worsened too. For years, she had been living with a rare blood marrow disorder. Now 77, she has spent the past six months in and out of hospital in Yeovil, their home town.

"I really believe if they could have remained active and living the life they had, it could be so different," Ms Quinn says.

Chronic illnesses

Natalie's family's story is being repeated across the country.

When the pandemic hit, about a quarter of adults in the UK were living with chronic illnesses.

With support and care disrupted and Covid making people more isolated and less active, their health has suffered.

According to those working in the NHS, they are now turning up to hospital in ever greater numbers.

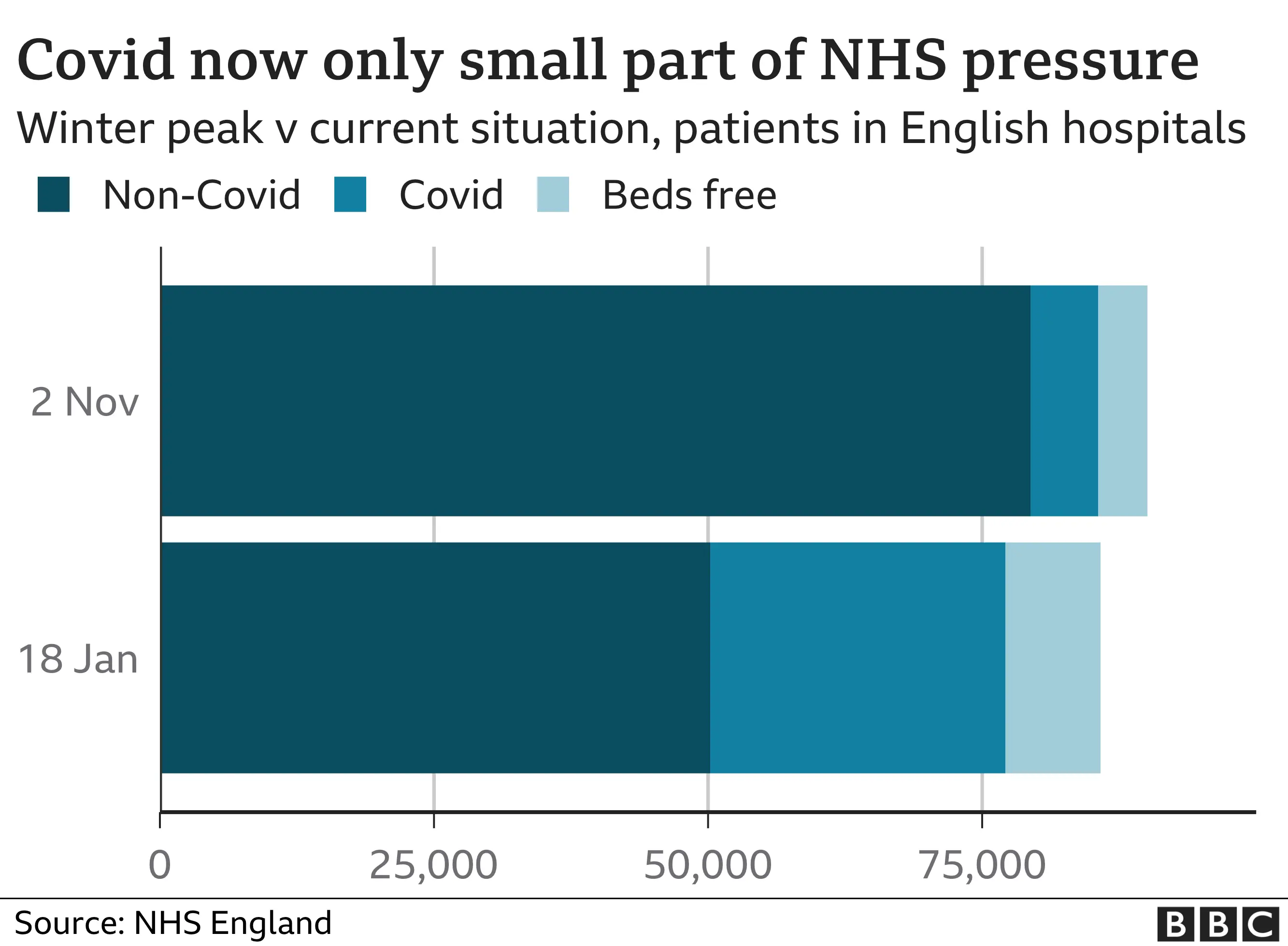

And it is this as much as Covid that is driving the rise in demand on the NHS.

At Newcastle's Royal Victoria Hospital, which allowed BBC News in to film this month, doctors and nurses are struggling.

Alongside Covid cases, they are seeing more frail elderly people being admitted as well as significant numbers of people with alcohol and mental health-related problems.

Like at nearly all hospitals, A&E waiting times have worsened and quality of care is suffering, with patients spending hours on trolleys because there are no beds available.

"It really breaks my heart to see - they are really vulnerable," senior sister Juliet Amos says.

'Tight spot'

The concern is being felt at the very top of the organisation too.

"We are in such a tight spot, there is no room for manoeuvre," Dame Jackie Daniel says. "It can't go on."

But this is not just about demand. It is also down to capacity - what the NHS can cope with.

The service was struggling before the pandemic hit, with targets routinely missed in all parts of the UK.

The NHS was being run "at its limit", Chris Hopson, of NHS Providers, which represents hospital trusts, says.

Feedback from his members now shows unprecedented levels of concern about the coming months. The health service, he believes, is heading for the "most difficult winter in its history".

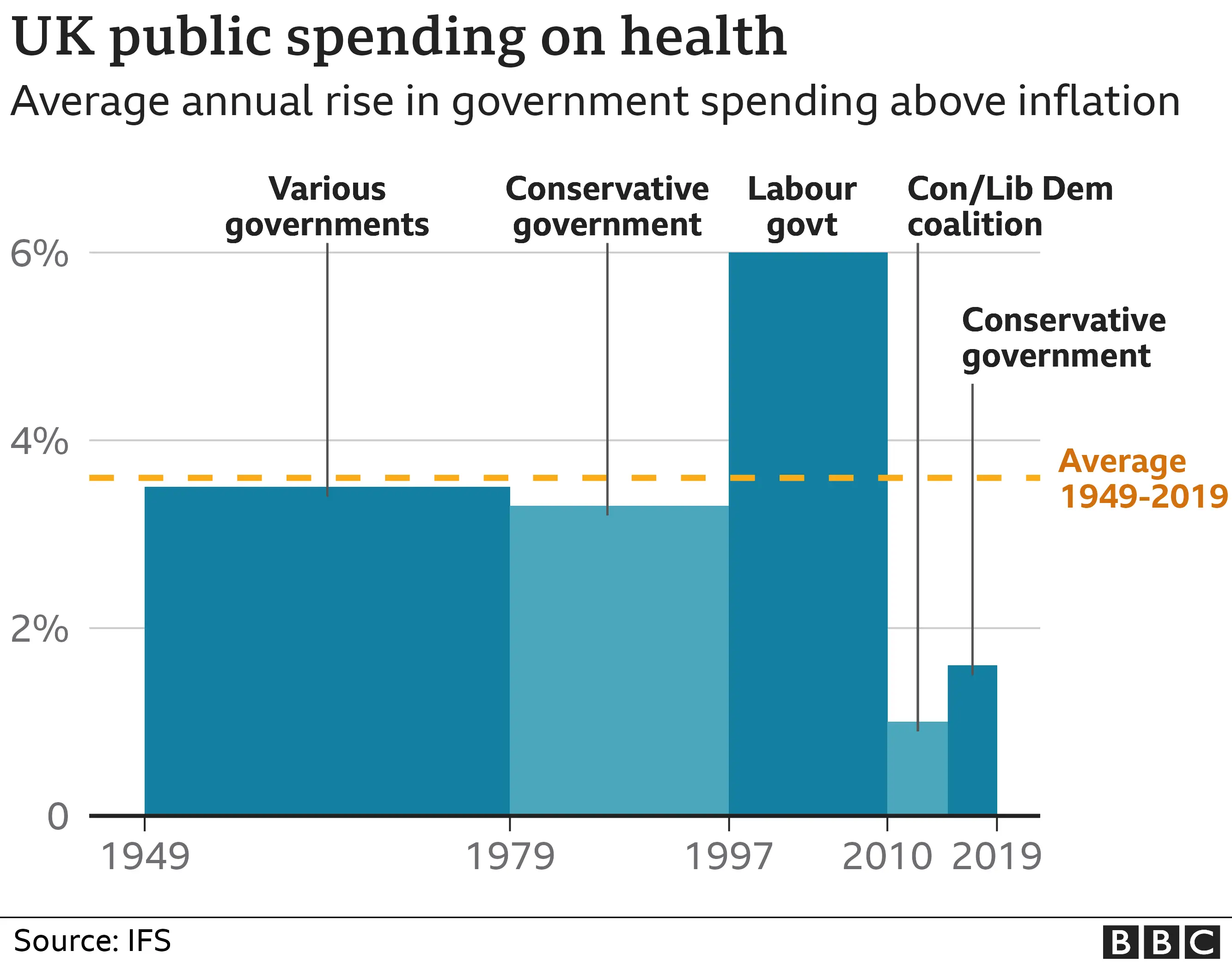

This is not just about the past couple of years though - the situation has been a decade in the making.

Between 2010 and 2019 the annual rises in spending on health were well below those traditionally given since the birth of the NHS.

During that period, the Tories have been in power - albeit with the Lib Dems for the first five years.

Although it is worth noting, in its 2010 and 2015 election manifestos, Labour was not proposing any tangibly higher increases in spending either.

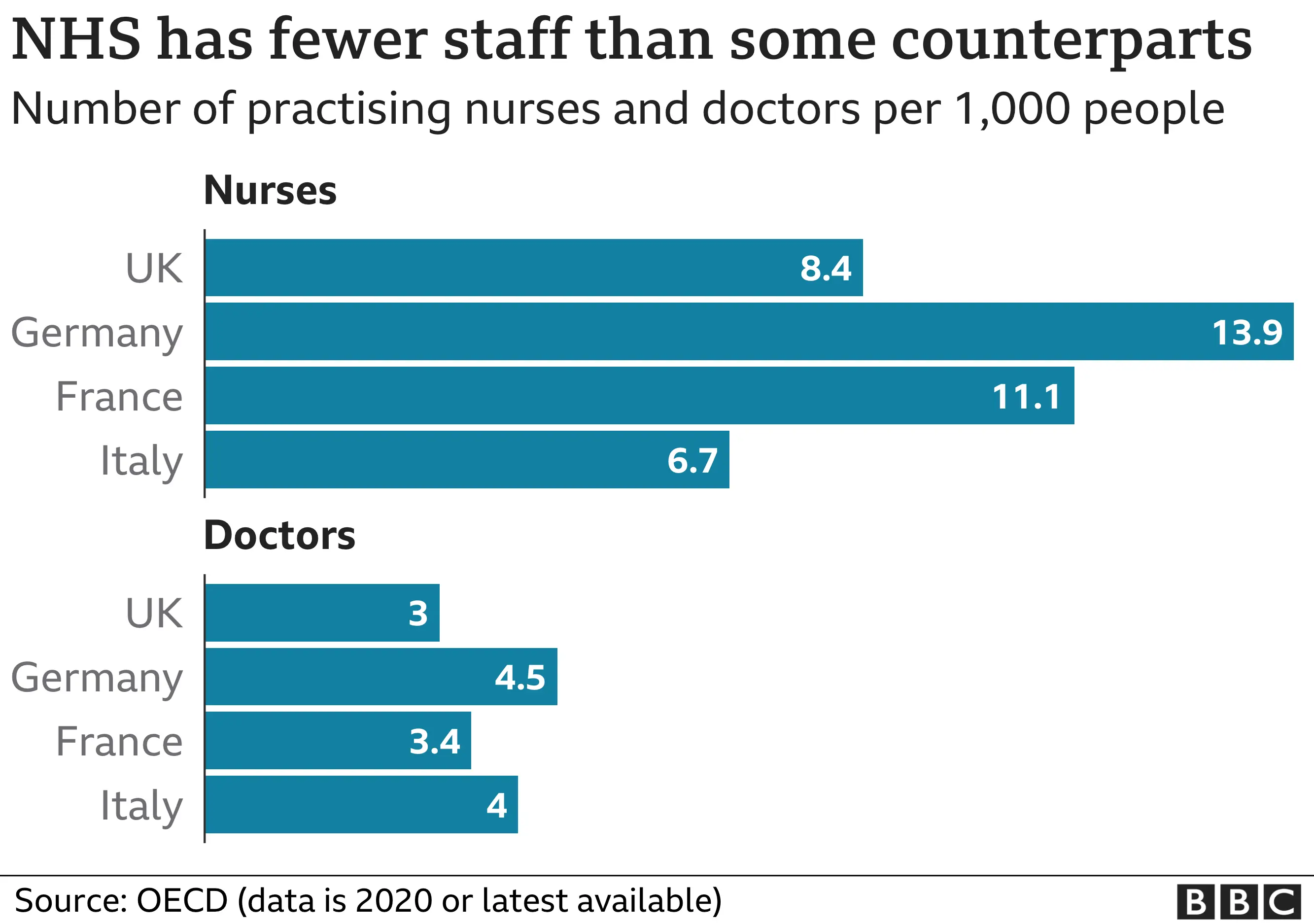

This parliament has seen a change - annual rises are now close to 4% - but the result of the squeeze in the 2010s is fewer doctors and nurses per head of population than our Western European neighbours.

It meant the UK entered the pandemic in a "vulnerable position" when you combine both funding and population health, says Dr Jennifer Dixon, chief executive of the Health Foundation, with less resilience to absorb a shock like a pandemic.

And so the NHS has struggled like never before.

The waiting times in A&E are now at their worst levels since records began, nearly 20 years ago.

The deterioration is even more alarming in the ambulance service, as BBC News reported last week.

Response times for emergency callouts for things such as heart attacks and strokes are taking three times longer than they should, with some patients waiting up to nine hours for help to arrive.

A big part of the problem is the system is grinding to a halt.

Ambulances are becoming stuck outside A&E for hours on end because there are no hospital staff available to hand their patients over to.

That's because of bottlenecks inside the hospital. Wards are full and struggling to discharge patients even when they are medically fit to leave - because of a lack of available care in the community.

So even when A&E patients are admitted, 30% wait longer than four hours for a bed.

And that, in turn, leads to further overcrowding in A&Es, where a quarter of all patients wait longer than four hours to be seen.

In one of the worst cases, a backlog of more than 20 ambulances was reported at one hospital.

EPA

EPAThis can have dire consequences. An investigation is under way after a patient died following a cardiac arrest.

They had spent five hours in the back of an ambulance outside Worcestershire Royal Hospital.

Another death is being investigated in the East of England, after a call classed as immediately life threatening took an hour to reach. Such calls should be answered in seven minutes on average. The patient was found dead.

The ambulance service said crews had been stuck in queues at local hospitals.

Winter hits

"Hospitals are full and running pretty much on one in and one out," a consultant in West Yorkshire, former Society for Acute Medicine president Dr Nick Scriven, says.

And it seems little can be done to prevent the situation deteriorating as winter hits.

The government is putting extra money in - but it will have limited effect without extra staff and they are simply unavailable, Dr Scriven says.

"We need to be frank with the public," he says. "Some really difficult decisions will have to be made."

Follow Nick on Twitter

Have you been affected by issues covered in this story? Share your experiences by emailing [email protected].

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

- WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

- Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay

- Upload pictures or video

- Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at [email protected]. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.