Resignation syndrome: Sweden's mystery illness

BBC

BBCFor nearly two decades Sweden has been battling a mysterious illness. Called Resignation Syndrome, it affects only the children of asylum-seekers, who withdraw completely, ceasing to walk or talk, or open their eyes. Eventually they recover. But why does this only seem to occur in Sweden?

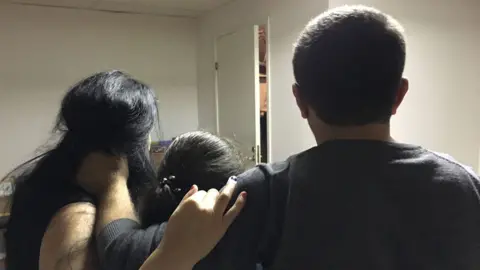

When her father picks her up from her wheelchair, nine-year-old Sophie is lifeless. In contrast, her hair is thick and shiny - like a healthy child's. But Sophie's eyes are closed. And under her tracksuit bottoms she wears a nappy. A transparent feeding tube runs into Sophie's nose - this is how she has been nourished for the past 20 months.

Sophie and her family are asylum seekers from the former USSR. They arrived in December 2015 and live in accommodation allocated to refugees in a small town in central Sweden.

"Her blood pressure is quite normal," says Dr Elisabeth Hultcrantz, a volunteer with Doctors of the World. "But she has a high pulse rate, so maybe she's reacting to so many people coming to visit her today."

Hultcrantz tests Sophie's reflexes. Everything works normally. But the child does not stir.

An ENT surgeon before she retired, Hultcrantz is worried because Sophie does not ever open her mouth. This could be dangerous, because if there were a problem with her feeding tube, Sophie could choke.

So how could a child who loved to dance become so deeply inert?

"When I explain to the parents what has happened, I tell them the world has been so terrible that Sophie has gone into herself and disconnected the conscious part of her brain," says Hultcrantz.

The health professionals who treat these children agree that trauma is what has caused them to withdraw from the world. The children who are most vulnerable are those who have witnessed extreme violence - often against their parents - or whose families have fled a deeply insecure environment.

Sophie's parents have a terrifying story of extortion and persecution by a local mafia. In September 2015 their car was stopped by men in police uniform.

"We were dragged out. Sophie was in the car so she witnessed me and her mother being roughly beaten," remembers Sophie's father.

The men let Sophie's mother go - she grabbed her daughter and ran. But Sophie's father did not escape.

"They took me away and then I don't remember anything," he says.

Sophie's mother took her to a friend's home. The little girl was very upset. She cried, shouted "Please go and find my dad!", and beat the wall with her feet.

Three days later, her father made contact, and from then on the family remained on the move, hiding in friends' homes until they left for Sweden three months later. On arrival, they were held for hours by Swedish police. Then, quite quickly, Sophie deteriorated.

"After a couple of days, I noticed she wasn't playing as much as she used to with her sister," says Sophie's mother, who is expecting a new baby next month.

Soon afterwards, the family was informed they could not stay in Sweden. Sophie heard everything in that meeting with the Migration Board, and it was at this point that she stopped speaking and eating.

Resignation Syndrome was first reported in Sweden in the late 1990s. More than 400 cases were reported in the two years from 2003-2005.

As more Swedes began to worry about the consequences of immigration, these "apathetic children", as they were known, became a huge political issue. There were reports the children were faking it, and that parents were poisoning their offspring to secure residence. None of those stories were proven.

Over the last decade, the number of children reported to be suffering from Resignation Syndrome has decreased. Sweden's National Board of Health recently stated there were 169 cases in 2015 and 2016.

It remains the case that children from particular geographical and ethnic groups are the most vulnerable: those from the former USSR, the Balkans, Roma children, and most recently the Yazidi. Only a tiny number have been unaccompanied migrants, none have been African, and very few have been Asian. Unlike Sophie, the children affected have often been living in Sweden for years, speak the language and are well-adjusted to their new, Nordic lives.

Numerous conditions resembling Resignation Syndrome have been reported before - among Nazi concentration camp inmates, for example. In the UK, a similar condition - Pervasive Refusal Syndrome - was identified in children in the early 1990s, but there have been only a tiny handful of cases, and none of them among asylum seekers.

"To our knowledge, no cases have been established outside of Sweden," writes Dr Karl Sallin, a paediatrician at the Astrid Lindgren Children's Hospital, part of Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

Find out more

Listen to Sweden's Child Migrant Mystery on Assignment, on the BBC World Service

For transmission times or to catch up online, click here

So how can an illness respect national boundaries? There is no definitive answer to that question, says Sallin, who is researching Resignation Syndrome for his PhD.

"The most plausible explanation is that there are some sort of socio-cultural factors that are necessary in order for this condition to develop. A certain way of reacting or responding to traumatic events seems to be legitimised in a certain context."

So somehow - and we do not know the mechanism for this, and why it should happen in Sweden - the kind of symptoms displayed by the children are culturally sanctioned: this is a way the children are allowed to express their trauma. If that is the case, it raises an interesting question: could Resignation Syndrome be contagious?

"That is sort of implicit in the model. That if you provide the right sort of nourishment for those kinds of behaviours in a society, you will also see more cases," says Sallin.

"If you look at the very first case in 1998 in the north of Sweden, as soon as that case was reported, there were other cases emerging in the same area. And there have also been cases of siblings where first one develops it and then the other. But it should be noted that researchers who proposed that model of disease, they are not certain that there needs to be direct contact between cases. It's a topic for research."

Here Sallin hits on the main obstacle to understanding Resignation Syndrome - the lack of research into it. No-one has done follow-up on what happens to these children, but we do know that they survive.

For Sophie's parents, that is hard to believe. They have seen no change in their daughter in 20 months. Their days are punctuated by Sophie's regime - exercises to stop her muscles wasting, attempts to engage her with music and cartoons, walks outside in a wheelchair, feeding and changing.

"You need to harden your heart with these cases," says Sophie's paediatrician, Dr Lars Dagson, who has seen her regularly throughout her illness.

"I can only keep her alive. I can't make her better, because as doctors we don't decide if these children can stay in Sweden or not."

Dagson shares the view commonly held among doctors treating children with Resignation Syndrome, that recovery depends on them feeling secure and that it is a permanent residence permit that kick-starts that process.

"In some way the child will have to sense that there's hope, something to live for… That's the only way I can explain why having the right to stay would, in all the cases I've seen so far, change the situation."

Until recently, families with a sick child were allowed to stay. But the arrival of some 300,000 migrants in the last three years has led to a change of heart.

Last year, a new temporary law came into force that limits all asylum seekers' chances of being granted permanent residence. Applicants are granted either a three-year or 13-month visa. Sophie's family have the latter, and it expires in March next year.

"What happens afterwards? The real issue hasn't been dealt with - it's limbo," says Dagson.

He doubts Sophie will recover in 13 months.

"I can't say it's not possible, but it all depends how the parents sense this - are we going to stay after these 13 months? If they're not sure about that, they cannot give Sophie the sense that everything is OK."

But evidence from the town of Skara in the south of Sweden suggests that there is a way of curing children with Resignation Syndrome even if the family doesn't receive permanent residence.

"From our point of view, this particular sickness has to do with former trauma, not asylum," says Annica Carlshamre, a senior social worker for Gryning Health, a company that runs Solsidan, a home for all kinds of troubled children.

When children witness violence or threats against a parent, their most significant connection in the world is ripped apart, the carers at Solsidan believe.

"Then the child understands - my mother can't take care of me," Carlshamre explains. "And they give up hope, because they know they are totally dependent on the parent. When that happens, to where or what can the child turn?"

That family connection must be re-built, but first the child must begin to recover, so Solsidan's first step is to separate the children from their parents.

"We keep the family informed about their progress, but we don't let them talk because the child must depend on our staff. Once we have separated the child, it takes only a few days, until we see the first signs that, yes, she's still there…"

All conversations about the migration process are banned in front of the child.

The children get up every day. They have day clothes and night clothes, and experienced staff like Clara Ogren, help them colour or draw by holding their hands to grip a pencil.

"We play for them until they can play on their own. And we goof around a lot and dance and listen to music. We want to bring all their senses to life. So we might take a little bit of Coca Cola, and put it in their mouth so they taste something sweet. Even if they are tube-fed, we put them in the kitchen so they smell food," she says.

"We have an expectation that they want to live, and all their abilities are still there, but they just forgot or lost the sense of using them. This work takes a lot of energy because we have to live for the children until they start to live on their own."

The longest time it took for a child to recover was six months.

Often the children will have no contact with their parents until they are able to talk to them on the phone.

Of the 35 children Calshamre has met over the years, one of them got permission to stay in Sweden while still at Solsidan. The others recovered before their asylum status was assured.

A book - The Way Back - has recently been published about Solsidan, but its work is not well-known. Could this kind of treatment help Sophie? Twenty months is a very long time for a child of her age to be disengaged from the world. What do her parents think will aid her recovery?

"Maybe the new baby when it comes will help," says Sophie's father.

Sophie's mother can only repeat what she has heard from the doctor.

"In order for Sophie to wake up, the doctor says she and her family should feel safe."

Their biggest fear is that they will be deported back to where they came from, and that the men who drove them out will find them.

"They promised they will kill us. There is nothing more devastating that can happen."

In order to protect the family's identity, Sophie's name has been changed