What has really happened since Macpherson's report

BBC

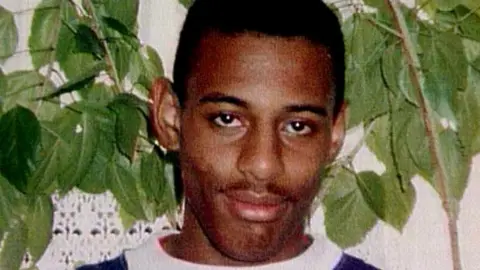

BBCIt has been 20 years since the publication of a report into the murder of Stephen Lawrence, a black teenager who had been stabbed to death in a racist attack in south-east London.

After his murder, a public inquiry - the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry - was ordered by the government.

Led by retired judge Sir William Macpherson, the inquiry published its findings on 24 February 1999.

But out of the 350-page report, two words had the biggest impact.

Sir William labelled London's Metropolitan Police as "institutionally racist".

Twenty years on, what do people think of the police service he criticised with such force?

'Disheartened and appalled'

Yvonne Lawson says she is "disheartened and appalled" to hear what young people think of the police.

She is the founder of the Godwin Lawson foundation, set-up after her 17-year-old son, Godwin, was stabbed to death in 2011.

In January, her foundation - aimed as reducing gang and knife crime - published a report after speaking to young people in Haringey, north London.

"We interviewed over 70 young people who expressed the same concerns I had 20 years ago.

"Most of the young people we spoke to said they didn't trust the police and wouldn't even call them when they or their friends were in danger."

She says not enough is being done to bridge the gap between black and ethnic minority communities and the police.

"One young person was even convinced the force didn't hire black people," she says.

"This is why we need more diversity. More young people from these backgrounds need to feel like they can identify with the police.

"This issue of trust kept coming up and once you identify with someone, you immediately start trust them more."

'They are still institutionally racist'

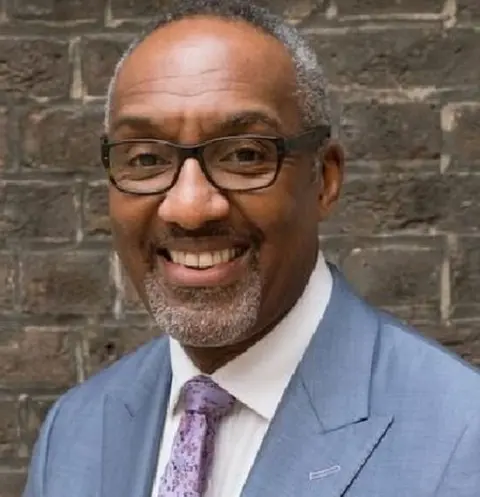

Leroy Logan, 62, is a former Met officer and ex-chairman of the National Black Police Association.

Twenty years after Macpherson, he says the force remains institutionally racist.

Logan says improvements were made post-Macpherson, such as hate crimes now being identified, but adds: "We still don't have the promotion of equality and justice in the organisation.

"Black officers are disproportionately subjected to discipline compared to their white counterparts.

"You still see black staff hugging the lower ranks and they aren't breaking through to the upper levels of the organisation."

He adds: "We still have disproportionality in stop and search, where a black person is five times more likely to be stopped by police than their white counterparts.

"They are 20 times more likely to be stopped under section 60 roadblocks and you are more likely to be Tasered if you are black.

"So even if this is unconscious bias, the fact the police force know these figures but have not decided to question why this is happening and haven't addressed it - it is institutionally racist."

Logan runs a leadership programme called Voyage Youth and says the young people he works with have the same attitude towards the police as he did in his younger years.

"They say they are over-policed and under-protected. They don't feel safe."

He adds: "In London we have white British gangs, Bengali gangs, eastern European, you name it.

"So why is it that 80% of them on the [police] gangs matrix is black? What happened to the rest of them?"

'There's still more to do'

PA

PASir William Macpherson, a retired high court judge from rural Scotland, led the public inquiry into Mr Lawrence's murder and wrote the final report, and the findings he still stands by.

"I couldn't work miracles about making the police behave better or improving the relationships between black and white people.

"But I hoped that the inquiry might assist," he said.

At the time, the public inquiry heard from more than 80 witnesses and considered 100,000 pages of documents.

Sir William said the police needed to re-establish trust with minority ethnic communities.

He says he recognised there was a problem within the force, which was "worse than individual acts of racism".

Sir William says that he has been through his initial report "over and over again" since 1999 and stands by the recommendations he made.

He says the report allowed police to take a step in the right direction, but adds: "There's obviously a great deal more to be done."

Find out more

Macpherson: What Happened Next presented airs on BBC Radio 4 at 11:00 GMT on Monday 11 March.

Or catch up later online.

'More accountability'

PA

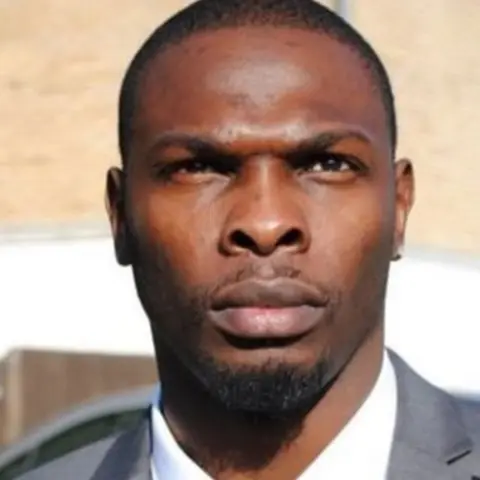

PAGwenton Sloley, 35, served three years in prison for armed robbery before going on to become one of Britain's leading anti-gangs advisors.

He has helped set up witness protection programmes, trained Met police officers, and had national contracts to work with young people.

But he too says the police are still institutionally racist.

Mr Sloley says the 1999 report gave minorities "a voice at a time when a lot of people were suffering in silence".

But he says there still needs to be "more accountability".

'Not about racist slurs'

Hackney CVS

Hackney CVS Tim Head, 25, is a volunteer for Hackney's Stop and Search Monitoring group and the Youth Independence Advisory Group, (YIAG).

"The impact of the report is felt in many ways and still talked about a lot, I think in terms of the rhetoric it's had a huge impact.

"In terms of actual changes on the ground, it's difficult to measure."

Despite the Met's claim that today's force is "utterly different" to 20 years ago, he says "a lot of the issues raised by Macpherson are still present".

"This isn't about officers using racist slurs, its about something much wider, much more structural. It's about the way demographics are policed.

"You can have very well meaning officers, who still support racist structures, even if their own personal beliefs aren't racist."

'This is an utterly different force'

Reuters

ReutersCressida Dick, Britain's most senior police officer, believes the Macpherson Report was "the most important thing that's happened in my service".

The Metropolitan Police Commissioner says Macpherson "defined my generation of policing", adding: "We're not at all complacent."

Currently 14% of Met officers are from BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic) backgrounds.

However, 40% of London's population comes from BAME backgrounds.

This means, if the Met continues to recruit at this rate, it will take 100 years to build a workforce that truly reflects the community it serves.

Despite this, Ms Dick says she does not believe the force is still institutionally racist.

"I simply don't see it as a helpful or accurate description. This is an utterly different Metropolitan Police", she claimed.