Cost of living: Why are things so hard for so many people?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMillions of the poorest people in the UK will begin to receive the first half of a £650 government grant on Thursday.

The payment is to help with the soaring cost of living, but many of those eligible were struggling long before now.

Here are five things that helped to create a perfect storm for the recent price rises.

Food bank explosion

In March this year, just as energy bills were set to soar, an estimated 6.7m people were already using a food bank or food charity to help them eat.

A further 9.9m across England, Wales and Northern Ireland - more than one in five people who responded to a survey - said they'd skipped a meal or cut down on portion sizes.

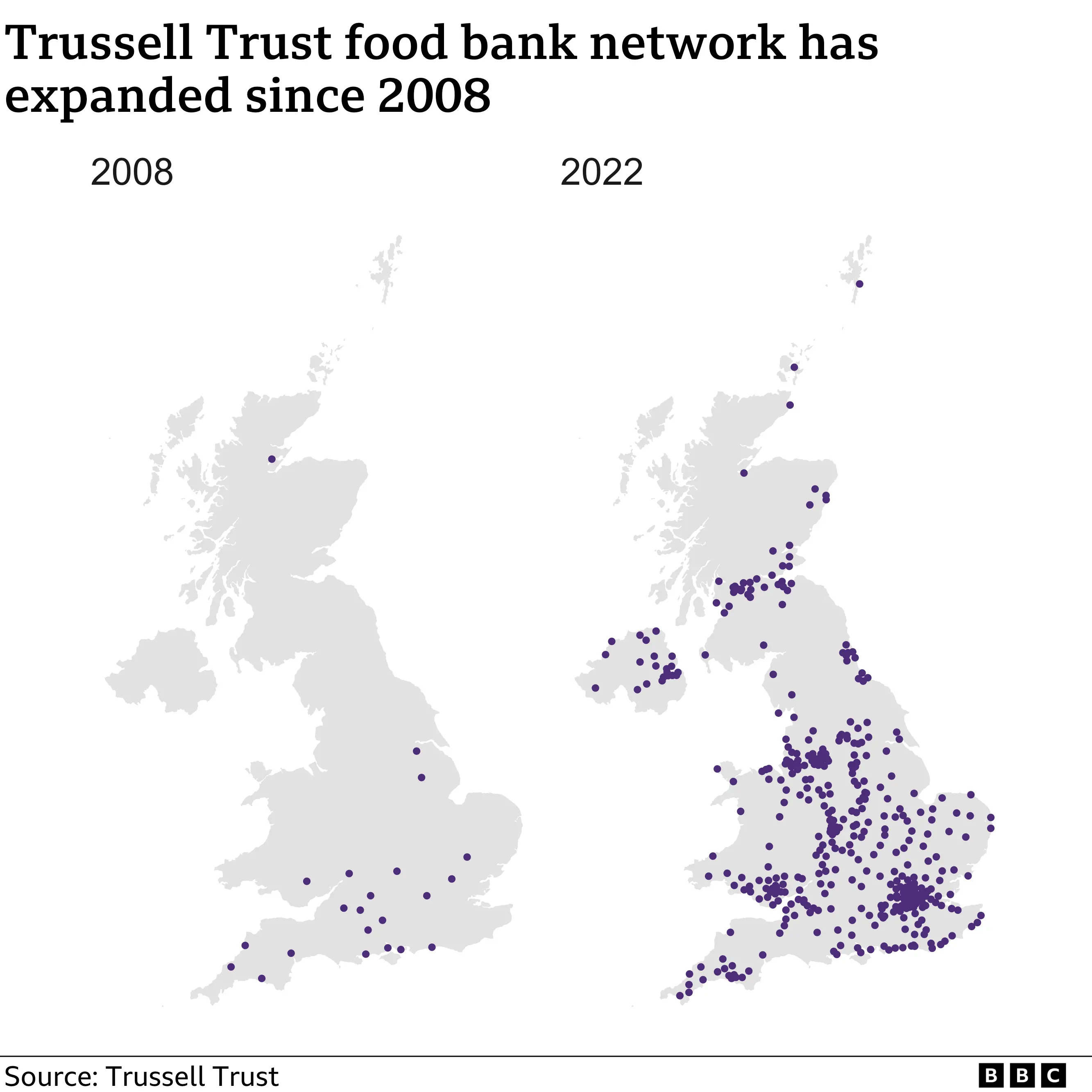

The Trussell Trust, the UK's largest food bank provider, has had a front row seat to these struggles. After opening its first food bank in Salisbury in 2000, it was operating in about 20 locations by the time of the 2008 financial crisis.

Fast forward to 2022, and the charity now runs nearly 400 food banks, with 1,300 places in its network where people can collect food. Hundreds more outlets are run by other organisations - it is estimated there are 3,000 food banks UK-wide.

The Trussell Trust's chief executive, Emma Revie, says the expansion is partly down to the fall in benefits, once inflation is taken into account.

For instance, the four-year benefit freeze, which started in 2016, meant the country's poorest seven million families lost out on an estimated £2,000 over that period.

"Food banks in our network have opened in response to an increasing number of people in their local area unable to afford the essentials. We know that the falling value of working-age benefits is fundamental to driving the need for foodbanks," says Ms Revie.

Rise of insecure jobs

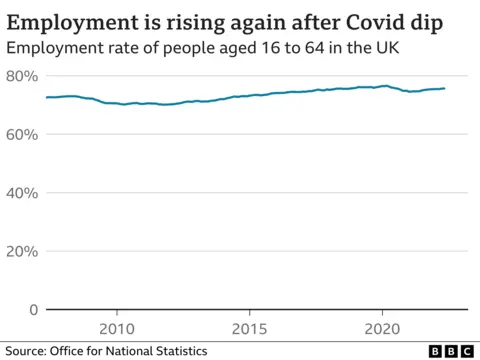

What's striking about the huge increase in food banks is that it has largely coincided with a massive rise in employment.

The number of people in work increased by more than four million in the decade to February 2020. Going into the Covid-19 pandemic, a record 76.6% of people in the UK were employed.

The government emphasises that this means almost two million more women and a million more disabled people are in work, and that it has "consistently focused on getting people into employment and making sure work pays".

But other recent employment trends have arguably been less positive.

For example, the number of people employed on zero-hour contracts - which do not guarantee any shifts - hit one million in the first three months of 2022, up by more than 400,000 from late 2013.

There has also been a rise in workers looking for extra employment, with almost a fifth of people in low-paid jobs saying they'd like to work more hours than they can find.

Stagnant pay for 20 years

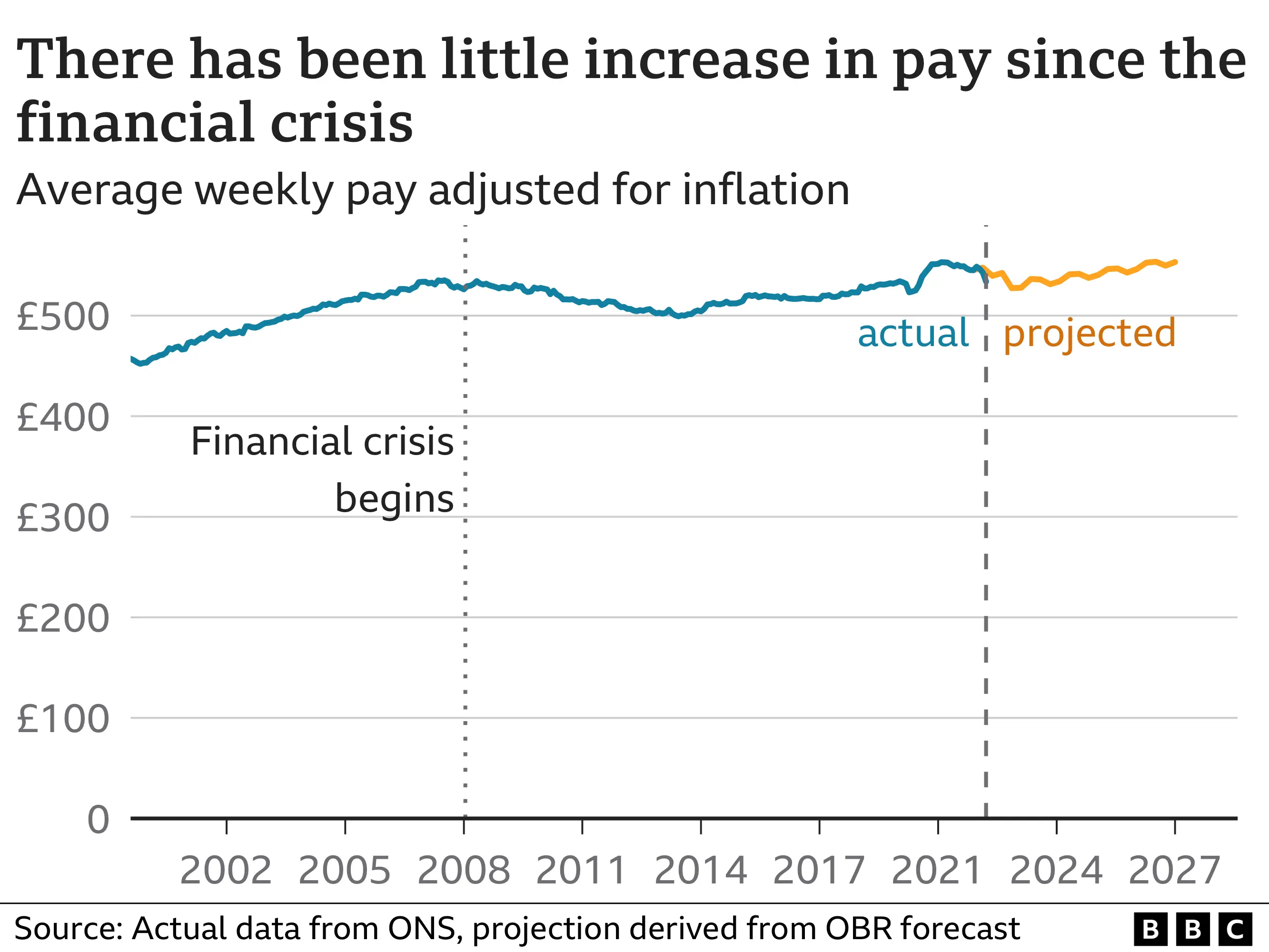

Pay hasn't increased much either, meaning many people have lower savings and are less able to cope with the recent price rises.

While average weekly pay has been climbing slightly since 2014, it's at a slow rate and projected to remain sluggish. While people may not be paid less than before, higher costs are making them feel poorer.

It's part of an "unprecedented" stagnation in living standards over the past 15 years, the Resolution Foundation says.

"One of the reasons why the current cost-of-living crisis is so painful for families," says Mike Brewer, chief economist at the think tank, is that their pay packets "have failed to grow at all in real terms over the course of the 2010s".

Rising in-work poverty

Yet while pay has stagnated for most people, the government points out that the poorest workers have received a boost through the growth in the National Living Wage.

At £9.50 an hour for over-23s, it is 42% higher than it was in 2015, making it one of the highest minimum wages in the world. However, two factors have limited the positive impact of this.

Families working minimum-wage jobs often require the benefits system to top up their incomes. But years of benefit changes, cuts and freezes have taken more than £30bn out of the welfare budget for working-age households.

Secondly, as more people move into the private rented sector, rising housing costs have undermined the benefit that higher employment levels and better pay for the worst-off should have brought.

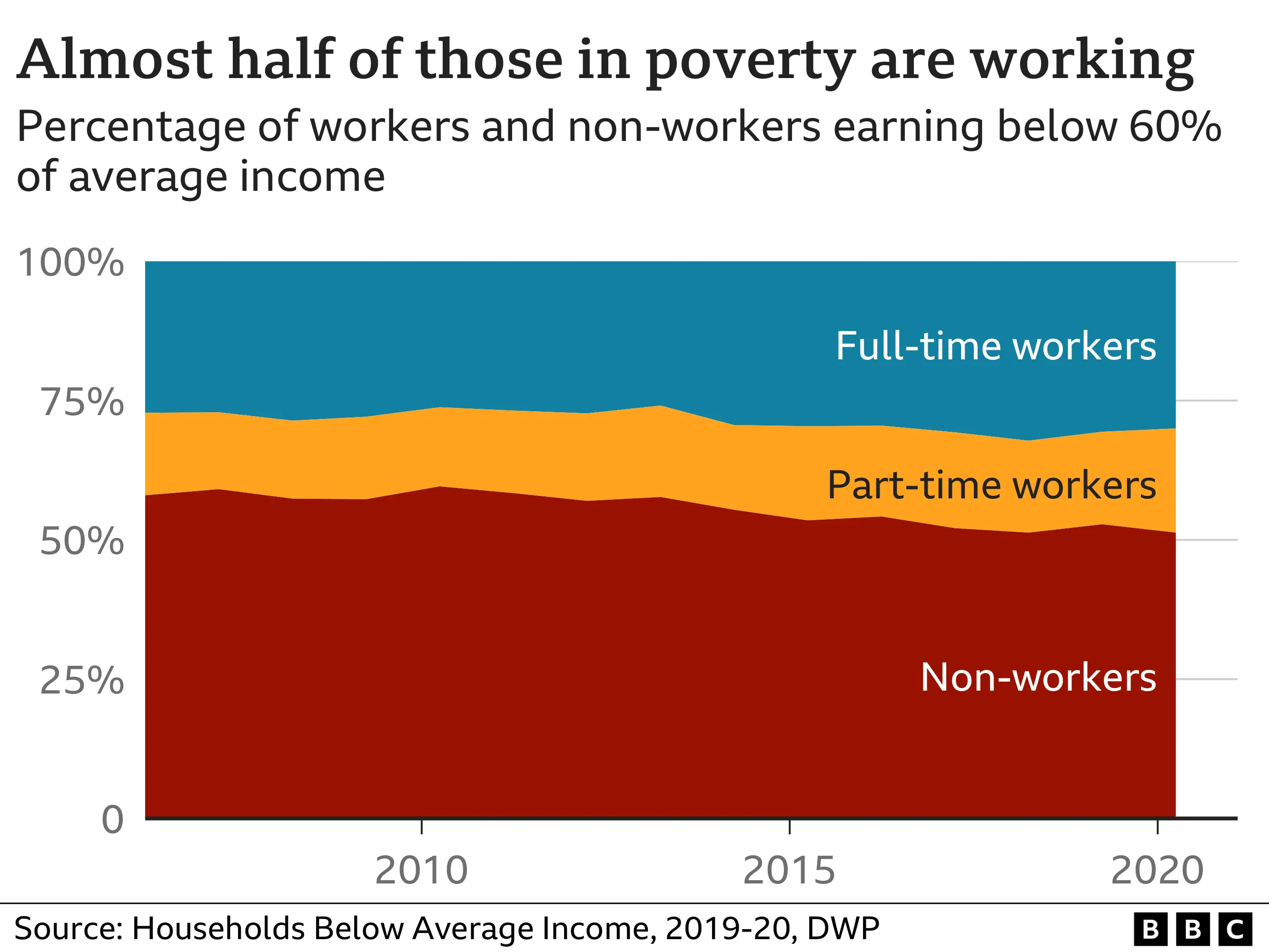

The consequence of this is that most people in poverty now live in a family in which someone has a job, according to anti-poverty think tank the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

"There have been some positive changes for people in work, but that tends to be for those who are able to work more hours," its Principal Policy Adviser Katie Schmuecker says.

"Those who have caring responsibilities, or an illness or disability that means their working hours are constrained, have been hit harder by cuts or freezes to universal credit."

On top of this, lower-income households were more likely to build up debt in the pandemic, while wealthier groups could save. For these reasons, she says, working doesn't always guarantee an escape from poverty.

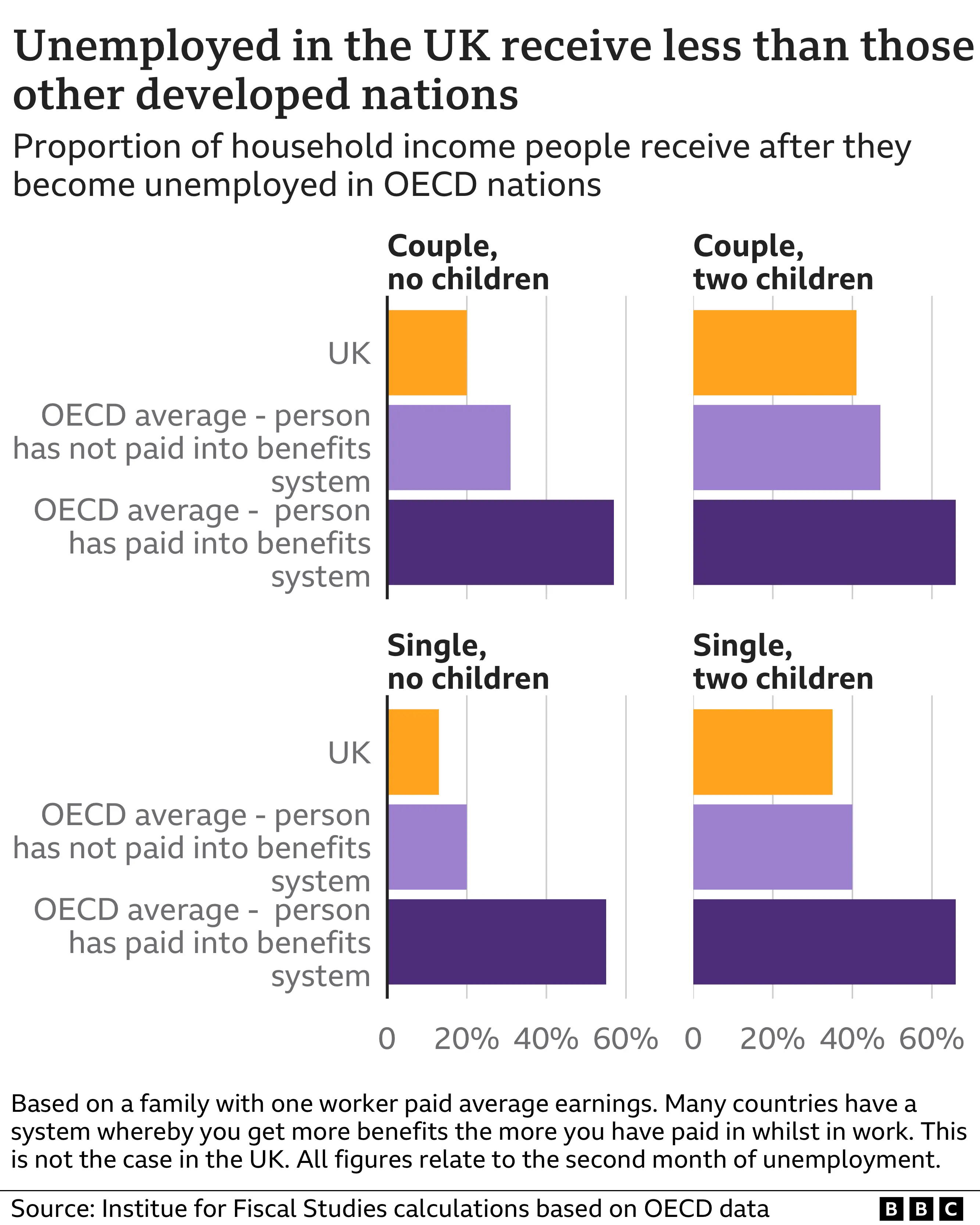

UK jobseekers are some of worst-off

What about people who become unemployed? If a single person in the UK loses their job, they get paid 13% of average earnings in Job Seekers Allowance - currently £77 a week for over-25s.

That is the lowest proportion of the developed OECD nations. The highest is Luxembourg, which pays 86%. UK jobseekers in couples, families, or single parent households, also receive less than the OECD average.

And because incomes haven't grown much in recent years, jobseekers are unlikely to have the savings to help them get through.

More than half of the poorest families have less than a month's savings, while an estimated 13% of UK adults have no savings at all.

Ministers highlight that there were almost a million fewer people living in absolute poverty in 2020 than 10 years earlier. But lower savings, insecure employment and higher outgoings on things like rent, mean many simply cannot absorb the extra costs they are now having to deal with on a daily basis.

Are you struggling with the rising cost of living? Email: [email protected].

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

- WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

- Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay

- Upload pictures or video

- Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at [email protected]. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.