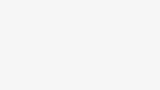

Rohingya crisis: How much power does Aung San Suu Kyi really have?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe huge exodus of Rohingya from Myanmar's Rakhine State, and the brutal tactics of the security forces, have stirred up strong condemnations of the Nobel Laureate and de-facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, who has defended her government's actions as a legitimate response to terrorism. As it emerges Ms Suu Kyi will miss next week's UN General Assembly debate, how much power does she really have inside her country?

Aung San Suu Kyi's formal title is "state counsellor". It is a position she created to get around a clause in the constitution - aimed specifically at her - that bars anyone with a foreign spouse or foreign children from the presidency.

Ms Suu Kyi is by far the most popular political figure in Myanmar and she led her National League for Democracy (NLD) to a landslide victory in the 2015 election. She makes most of the important decisions in her party and cabinet. She also holds the position of foreign minister.

In practice, the actual president, Htin Kyaw, answers to her.

The constitution was drafted by the previous military government, which had been in power in one form or another since 1962. It was approved in a questionable referendum in 2008. At the time, it was not recognised by the NLD or Ms Suu Kyi.

It was the key to the military's declared plan to ensure it still had a guiding role in what it called a "discipline-flourishing democracy". Under it, the armed forces are guaranteed one quarter of the seats in parliament.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe military retains control of three vital ministries - home affairs, defence and border affairs. That means it also controls the police.

Six out of 11 seats on the powerful National Defence and Security Council, which has the power to suspend democratic government, are military appointees.

Former military personnel occupy many top civil positions. The military also still has significant business interests. Defence spending is still 14% of the budget, more than health and education combined.

For more than 20 years the military and Aung San Suu Kyi were bitterly opposed. She spent 15 of those years under house arrest.

AFP

AFPAfter the election, they had to find ways to work together. She had the mandate. The generals had the real power.

They still disagreed on important issues, like amending the constitution, which she wants, and the pace of peace talks with the various ethnic armies that have been fighting the government from Myanmar's borders for the past 70 years.

But they agreed on the need to reform and improve the economy and the need for stability - "rule of law" is Ms Suu Kyi's favourite mantra - at a time when rapid change has been stirring up social tension.

Increasing hostility

But on the issue of the Rohingya, Ms Suu Kyi must tread carefully. There is little public sympathy for the Rohingya.

Much of the Burmese population agrees with the official view that they are not citizens of Myanmar, but illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, even though many Rohingya families have been in the country for generations.

That hostility has increased markedly after the attacks on police posts by militants from the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army in October last year and this August.

Inside Rakhine State, the local Buddhist population are even more hostile. Conflict between them and the Rohingya - who they refer to as Bengalis - goes back many decades.

Many Rakhine Buddhists believe they will eventually become a minority, and fear that their identity will be destroyed. The Rakhine nationalist party, the ANP, dominates the local assembly, one of the few not controlled by Ms Suu Kyi's NLD.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere is strong sympathy for them among the police - almost half of whose officers are Rakhine Buddhist - and the military.

The military is the real power in northern Rakhine State, along the border with Bangladesh, where access is tightly controlled.

And the powerful armed forces commander, Gen Min Aung Hlaing, has made it clear he has little sympathy for the Rohingya.

Independent media

He has referred to the current "clearance" operations there as necessary to finish a problem that dates back to 1942, a period of shifting front lines between Japanese and British forces that saw bitter communal fighting between Rohingya and Rakhine Buddhists.

The military sees itself now as fighting an externally funded terrorist movement, a view shared by much of the public.

It seems to be applying its "four cuts" strategy, used in other conflict areas, in which soldiers destroy and terrorise communities thought to be giving support to insurgencies.

The media is also a factor. One of the biggest changes in Myanmar over the past five years has been the proliferation of new, independent media outlets, and the dramatic growth of mobile phone and internet use, in a country that scarcely had landlines a decade ago.

Moral authority?

But very few media have shown what is happening inside Bangladesh, or the suffering of the Rohingya. Most have focused instead on displaced Buddhists and Hindus inside Rakhine, who are far fewer in number. The popularity of social media has allowed disinformation and hate speech to spread quickly.

So Aung San Suu Kyi has very little power over events in Rakhine State. And speaking out in support of the Rohingya would almost certainly prompt an angry reaction from Buddhist nationalists.

Whether, with her immense moral authority, it might start to change public prejudice against the Rohingya, is an open question. She has calculated that it is a gamble not worth taking. She is known to be very stubborn once she has made up her mind.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIs there a risk that the military might step in and replace her, should she challenge what they are doing in Rakhine? They have the power to do so. In the current climate, they might even have some public support.

But it is worth remembering that the current power-sharing arrangements with the NLD are more or less what the military was aiming for when it announced its Seven Stage Roadmap to Democracy back in 2003.

At the time this was dismissed as a sham. But it turns out Myanmar's political development over the next 14 years followed that roadmap closely. Even after its own political party was trounced in 2015's election, the military remains by far the most powerful institution in the country.

Only this time, it has Aung San Suu Kyi as a shield, to be battered by the international outcry over its actions.