The German group buying ticket dodgers out of prison

BBC

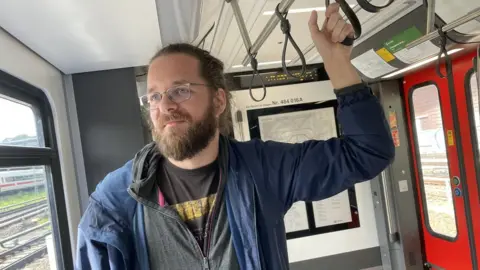

BBCOne day in late 2021, Arne Semsrott set out with €20,000 ($21,200; £17,000) stuffed into his pockets. Some of it was his, some he had borrowed from friends. He admits to having been a little nervous.

"I had no idea if this was going to work," he says.

His destination was the Plötzensee prison in the north-west of Berlin. His plan was to buy out as many prisoners as the cash in his pockets would allow.

Arne, a 35-year-old journalist and activist, had discovered a loophole in the German legal system.

Someone sentenced to pay a fine doesn't have to pay it themselves. In exploiting the loophole he hoped to draw attention to what he saw as a glaring injustice: the law that enables judges to send people to prison for not buying a ticket on public transport.

"We freed 12 men from Plötzensee that day and nine women from the Lichtenberg prison the next day," he says.

Since then, Arne and his organisation Freiheitsfonds (The Freedom Fund) has enabled around 850 people to walk free at a cost of more than €800,000.

Arne says he believes the law is unjust. "It discriminates heavily against people who don't have money, against people who don't have housing, against people who are already in crisis.

"We believe this law has to change because it is not something that you want in a democratic and just society."

It has been estimated that some 7,000 people are held in German prisons for not having paid their fare on a train, tram or bus. Most of them will have been sentenced initially to a fine and been unable to pay.

They are serving what's called an Ersatzfreiheittsstrafe - a substitute custodial sentence. But some will have gone straight to prison.

Gisa März falls into the second category. A small, fragile looking woman in her mid-50s, she has for years supported herself in part by selling the Düsseldorf street magazine fiftyfifty.

Gisa spent four months in prison from last November until March this year. She had been caught twice on trains in Düsseldorf without a ticket.

"I was on methadone," she explains, "the drug they give you when you're coming off heroin. And you have to go into the clinic every day.

"I didn't have any money. I was getting unemployment benefit, but it was the end of the month and I didn't have any money left."

Gisa was sentenced initially to six months in jail suspended for three years. But she failed to meet the conditions laid down by the court and eventually found herself behind bars.

Fiftyfifty worked hard to raise awareness of her case. There were demonstrations outside government buildings; reporters at a national news magazine visited her in prison; her circumstances were even raised in the Bundestag, the lower house of the German parliament.

Most people who take a bus journey without a ticket don't end up in prison. They pay the €60 penalty fare and that's the end of it.

But the public transport companies take a harder line with serial offenders. They are the ones who are referred for prosecution, regardless of whether or not they've paid the penalty fare.

Gisa was one of those. She was caught another seven times without a ticket in the period between her sentencing and finally going to prison. And she had previous convictions for the same offence.

Arne Semsrott wasn't able to help Gisa because she hadn't been sentenced to pay a fine. Nonetheless he believes people like her should never be sent to prison; and he says that many prison governors think the same thing.

"Prisons love the Freedom Fund," he says.

"Why? Because people who end up in prison for riding without a ticket just don't belong there. These are people with psychological problems, people who don't have housing, who need help from social services. Prisons are the wrong place for them."

He says that many prisons hand out the Freedom Fund's application form as people arrive to begin their sentences.

"So on the one hand the state criminalises people for this offence and then, on the other, the same state comes to civil society and asks for help to correct this. It really shows you the absurdity of it all."

Arne calculates that in buying out 850 people so far, his organisation has saved the state some €12m, based on the estimated cost per day of keeping someone in prison.

Public transport in Germany has resisted any change in the law. In a statement forwarded to the BBC, the head of the VDV, the organisation that represents more than 600 rail and bus companies, said it was "urgently necessary" to retain the threat of prison as a deterrent for serial offenders.

A spokesperson said that people not paying a fare costs the industry an estimated €300m a year.

It is unclear if the law will be changed before Germany's next parliamentary election in 2025. But the Gisa März case has been the catalyst for change in Düsseldorf.

The city council there has now ordered the local transport authority, Rheinbahn, not to prosecute those caught without a ticket.

Rheinbahn has confirmed to the BBC that it will abide by this instruction "until further notice".