The Amazon in Brazil is on fire - how bad is it?

Amnesty International

Amnesty InternationalThousands of fires are ravaging the Amazon rainforest in Brazil - the most intense blazes for almost a decade.

The northern states of Roraima, Acre, Rondônia and Amazonas have been particularly badly affected.

Huge fires have also been burning across the border in Bolivia, devastating swaths of the country's tropical forest and savannah.

So what's happening exactly and how bad are the fires?

There have been a lot of fires this year

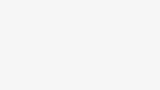

Brazil - home to more than half the Amazon rainforest - has seen a high number of fires in 2019, Brazilian space agency data suggests.

The National Institute for Space Research (Inpe) says its satellite data shows an 76% increase on the same period in 2018.

The official figures show more than 87,000 forest fires were recorded in Brazil in the first eight months of the year - the highest number since 2010. That compares with 49,000 in the same period in 2018.

Nasa, which provides Inpe with its active fire data, confirmed recordings from its satellite sensors also indicated 2019 had been the most active year for almost a decade.

However, 2019 is not the worst year in recent history. Brazil experienced more fire activity in the 2000s - with 2005 seeing more than 142,000 fires in the first eight months of the year.

Forest fires are common in the Amazon during the dry season, which runs from July to October. They can be caused by naturally occurring events, such as lightning strikes, but this year most are believed to have been started by farmers and loggers clearing land for crops or grazing.

There had been a noticeable increase in large, intense, and persistent fires along major roads in the central Brazilian Amazon, said Douglas Morton, head of the Biospheric Sciences Laboratory at Nasa's Goddard Space Flight Center.

The timing and location of the fires were more consistent with land clearing than with regional drought, he added.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesActivists say the anti-environment rhetoric of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has encouraged such tree-clearing activities since he came into power in January.

In response to criticism at home and abroad, Mr Bolsonaro announced he was banning setting fires to clear land for 60 days.

The president has also accepted an offer of four planes to fight the fires from the Chilean government and has deployed 44,000 soldiers to seven states to combat the fires.

However, he has refused a G7 offer of $22m (£18m) following a dispute with French President Emmanuel Macron.

The north of Brazil has been badly affected

Most of the worst-affected regions are in the north of the country.

Roraima, Acre, Rondônia and Amazonas all saw a large percentage increase in fires when compared with the average across the last four years (2015-2018).

Roraima saw a 141% increase, Acre 138%, Rondônia 115% and Amazonas 81%. Mato Grosso do Sul, further south, saw a 114% increase.

Amazonas, the largest state in Brazil, has declared a state of emergency.

Deliberate deforestation?

The recent increase in the number of fires in the Amazon is directly related to intentional deforestation and not the result of an extremely dry season, according to the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (Ipam).

Ipam's director Ane Alencar said fires were often used as a way of clearing land for cattle ranches after deforesting operations.

"They cut the trees, leave the wood to dry and later put fire to it, so that the ashes can fertilise the soil," she told the Mongabay website.

Planet Labs Inc

Planet Labs Inc

While the exact scale of deforestation in the rainforest will only be certain when 2019 figures are published at the end of the year, preliminary data suggests there has been a significant rise already this year.

Monthly data shows the scale of the areas cleared has been creeping up since January, but with a spike in July this year - almost 278% higher than in July 2018, according to Inpe.

Inpe tracks suspected deforestation in real-time using satellite data, sending out alerts to flag areas that may have been cleared.

More than 10,000 alerts were sent out in July alone.

The record number of fires also coincides with a sharp drop in fines being handed out for environmental violations, BBC analysis has found.

The fires are emitting large amounts of smoke and carbon

Plumes of smoke from the fires have spread across the Amazon region and beyond.

According to the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (Cams), a part of the European Union's Earth observation programme, the smoke has been travelling as far as the Atlantic coast.

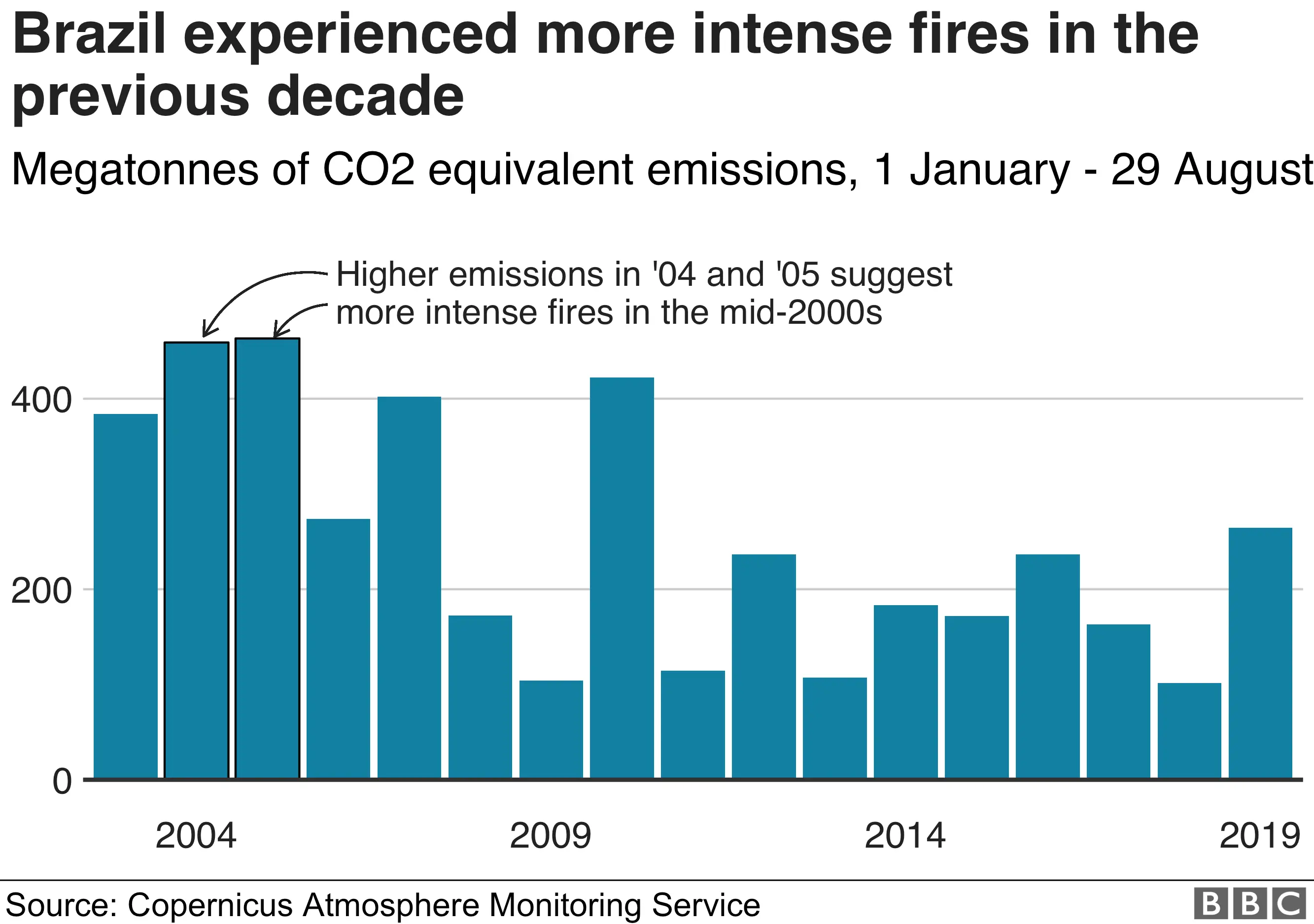

The fires have been releasing a large amount of carbon dioxide, the equivalent of 228 megatonnes so far this year, according to Cams, the highest since 2010.

They are also emitting carbon monoxide - a gas released when wood is burned and does not have much access to oxygen.

Maps from Cams show this carbon monoxide - a pollutant that is toxic at high levels - being carried beyond South America's coastlines.

The Amazon basin - home to about three million species of plants and animals, and one million indigenous people - is crucial to regulating global warming, with its forests absorbing millions of tonnes of carbon every year.

But when trees are cut or burned, the carbon they are storing is released into the atmosphere and the rainforest's capacity to absorb carbon is reduced.

There were more fires in the mid-2000s

While the number of fires in Brazil is at its highest level for almost a decade, the data suggests that Brazil - and the wider Amazon region - has experienced more intense burning in the past.

An analysis of Nasa satellite data this month indicated that the total fire activity in 2019 across the Amazon, not just Brazil, is close to the average when compared with a longer 15 year period.

Figures from Brazil's Inpe, dating back to 1998, also show the country suffered worse periods of fire activity in the 2000s.

Reports in mid-August, including on the BBC, had said there were a record number of fires in Brazil this year. Inpe has since made more data easily accessible, showing how far back its records stretched. We have now amended our reports to reflect this information.

Inpe's historic figures are backed by numbers from Cams, which show total CO2 equivalent emissions - used to measure of the amount and intensity of fire activity - were also higher in Brazil the mid-2000s.

Other countries have also been affected

A number of other countries in the Amazon basin - an area spanning 7.4m sq km (2.9m sq miles) - have also seen a high number of fires this year.

Venezuela has experienced the second-highest number, with more than 26,000 fires, with Bolivia coming in third, with more than 19,000. This is a rise of 79% on last year. Peru, in fifth place, has seen a rise of 92%.

The size of the fires in Bolivia is estimated to have doubled since late last week. About one million hectares - or more than 3,800 square miles - are affected.

Bolivia has hired a Boeing 747 "supertanker" from the US to drop water, and accepted an offer of aid from G7 leaders.

Extra emergency workers have also been sent to the region, and sanctuaries are being set up for animals escaping the flames.

South American countries are planning to meet in the Colombian city of Leticia next week to discuss a co-ordinated response to the fires.

By Lucy Rodgers, Nassos Stylianou, Clara Guibourg, Mike Hills and Dominic Bailey. Design by Mark Bryson.