Pastis: The French cocktail born from a banned spirit

Alamy

AlamyEver since absinthe was outlawed due to rumours it led to insanity, this simple drink has become the nation's go-to apertif.

It's difficult to imagine France without apéro (aperitif hour), that magic moment when time stops, and suddenly, everyone has a drink in hand.

In a country so proud of its regional products, it's not surprising that the contents of one's aperitif glass varies, from cassis-scented kir in Burgundy to beer on the Belgian border to cloudy aniseed-infused pastis in Marseille. But despite its strong association with southern France, conjuring images of lazy summer afternoons playing pétanque by the sea, one apéro spirit is omnipresent in France: pastis. Not only do sales of pastis represent one-fifth of all spirits sold nationwide, but it's the default aperitif drink as far north as Picardie.

"It's not like some of those other regional aperitifs," said Forest Collins, author of the book Drink Like a Local: Paris. "Pineau de Charentes, you're mainly going to find around Cognac. Pommeau, you're mainly going to find in Normandy. But it's pretty likely that anywhere in France, you might find a bottle of pastis."

Alamy

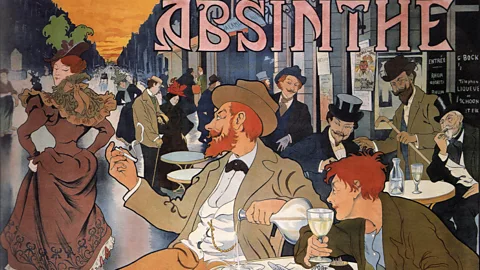

AlamyYet, pastis didn't become France's go-to aperitif by design. If not for the nation's 1915 ban of absinthe due to its alleged harmful effects and the marketing chops of Marseillais Paul Ricard, the herbal liqueur may never have become France's most famous.

Absinthe's quiet conquest of France occurred in the wake of the 19th Century phylloxera epidemic that wiped out nearly half of the country's vineyards. Soon, it supplanted not just wine but beer in the north, cider in Normandy and flavoured wines like quinquina, explained Marie-Claude Delahaye, author of the book L'Absinthe: Histoire de la Fée Verteand founder of the Musée de l'Absinthe in Auvers-sur-Oise. According to Delahaye, absinthe introduced aniseed to the aperitif hour, along with a "playful and convivial ritual" of diluting the 75% ABV liquor with sugar and water.

"It was the sprout of what could be an extraordinary success," Delahaye said. Yet, absinthe's rise to fame was stymied in 1915, when it was banned throughout the country following rumours that it led to insanity. Aficionados immediately began clamouring for something to fill the aniseed-scented gap. "If absinthe had continued to be commercialised," explained Delahaye, "pastis never would have appeared."

While pastis and absinthe share an aniseed flavour profile, the similarities stop there. Distilled absinthe boasts more complexity than sweetened, macerated pastis, and at 40 to 45% ABV, pastis' alcoholic power pales in comparison. This put pastis at an advantage, according to Collins: absinthe, she said, was seen as "the drink of degenerate artists" (including Edouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse Lautrec and Vincent Van Gogh, who even included the spirit in some of his paintings). With pastis, meanwhile, drinkers still got "that nice little buzz, and that nice aniseed flavour" without the negative connotations.

Alamy

Alamy"I think that's the effect that pastis had on aperitif culture," Collins said. "It allowed this drinking culture of aniseed to carry on."

Order a pastis in most cafes, and it'll be poured from a bottle emblazoned with a bright yellow sun and one name: Ricard. But before there was Ricard, there was Pernod – two Pernods, to be precise. Both Henri-Louis Pernod and the unrelated Jules-Félix Pernod launched anisettes in 1918, merging their companies in 1928. Ricard, meanwhile, only began selling his version in 1932. If Ricard's became the most famous, it's in large part thanks to his marketing chops. He appealed immediately to the French love of terroir, deriving the name of his anisette from the Provençal pastisson(mixture), and attributing his recipe to "a poacher … who knew all of the herbs of the mountains and the garriguesurrounding us". He soon set about disseminating the story – and the local liqueur – by going door to door to bistros and cafes across France.

How to apéro

Apéro hour usually takes place between 18:00 and 19:30, when France's squares and terraces fill with groups sipping golden demis of beer, pink kirs and pastis. Cafes typically serve a free bowl of crisps, pretzels or olives with your chosen apéro, though the food is secondary to the drinks and conversation. Apéro isn't about inebriation, and it's not uncommon for friends to nurse a drink for an hour before parting ways to have dinner at home.

"He used to say, 'Make a friend a day,'" said Gabrielle Arevikian-Xerri, brand director of Pernod-Ricard.

Perhaps Ricard's most successful initiative was merch. An amateur artist, Ricard created branded posters evoking sunny Marseille, not to mention glasses and ashtrays, bucket hats and caps. He released thousands of such objects during the 1948 Tour de France; today, they're omnipresent at French flea markets, where keen collectors track them down.

Alamy

AlamyJacky Roussial is one such collector. Over 39 years, Roussial has amassed no fewer than 3,500 Ricard-branded objects, including 180 different goblets, playing cards and umbrellas. His most prized pastis possession is a pichet tambourin, a 1950s-era pitcher depicting a tambourine player he dubs "the grail of any collector". It goes for about €4,000.

These pitchers aren't just trinkets; they're an essential part of serving pastis, a drink that's customisable by design. Each 2cl pour is meant to be diluted with water to taste. Many also sweeten their pastis with syrup: a blend of bright green mint and pastis is called a perroquet (parrot), while the addition of grenadine makes a tomate (tomato). Of them, Arevikian-Xerri said, the mauresque (a blend of pastis and local southern orgeat) is the most popular.

In recent years, modern mixologists have been toying with crafting more complex pastis cocktails. Margot Lecarpentier of Paris cocktail bar Combat likes blending it with cachaça to highlight floral notes, while Aurélie Panhelleux, co-founder of CopperBay cocktail bars in both Marseille and Paris, combines it with gin, lemon juice, dill-infused orgeat and citron to create the house Mauresco. But these creations remain anecdotal at best, according to Collins, who said that while there was an attempt to make a pastis-scented play on an Apérol Spritz popular about a decade ago, "it hasn't really happened."

"I think the traditional way is the way that pretty much anybody drinks pastis," she said.

Even Lecarpentier agrees. "Ninety-five percent of French people will tell you pastis is drunk with a glass of water and ice cubes," she said. "It would be weird to not serve it like that."

Alamy

AlamyPastis does incur a ritual, of sorts, as the drinker dilutes the spirit with water from a branded pitcher until it takes on its cloudy-yellow hue, adding syrup or ice to taste. According to Collins, the relative simplicity of how pastis is served – especially compared to absinthe, which was dripped into a glass through a sugar cube set on a special perforated spoon – is part of the drink's enduring popularity. "Everyone in their house can have a little pitcher, but not everybody is going to go out and get an absinthe fountain and absinthe spoons," she said.

Pastis' accessibility has cemented its place as the aperitif to rule all aperitifs. Drunk by men and women, by young and old, pastis is above all, according to Arevikian-Xerri, "for bringing people together. Whatever their background, whatever their social status."

But it's not just pastis that remains popular – it's Ricard. Other brands exist, of course, from high-end Henri Bardouin to organic Distillerie de la Plaine. Even Pernod, which merged with its one-time rival in 1975, has stood the test of time. But in 2022, Ricard wasn't just the most-sold pastis in France; it was the most-sold product in French hypermarkets, outranking mineral water, Coca-Cola and Nutella. In the leadup to Christmas 2024, Ricard outsold even Champagne.

"Pastis is a question of taste, and often of tradition," said Panhelleux. "In France, it's the only spirit people order by brand."

Alamy

Alamy"I don't drink pastis," echoed Roussial. "I drink Ricard."

Some of the drink's popularity still stems from the fantasy Ricard constructed. "It's the symbol of sunshine, of holidays, of the Mediterranean, of far niente (the art of doing nothing), of conviviality," said Roussial. But connotations aside, for Collins, its charm comes above all from its omnipresence.

"For most people, it's just a way of life. Almost like a [table wine]," she said.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.