Ghost in the machine? How a 'haunted' N64 video game cartridge terrified children around the world

Alamy/ BBC

Alamy/ BBCA second-hand Zelda cartridge. A cryptic forum thread. A generation of frightened children. This is the story of Ben Drowned – the internet's most infamous video game ghost.

It was Christmas Eve and 10-year-old Saarthak Johri couldn't sleep – but not because of excitement. He was shot through with fear. It was roughly a decade ago and Johri was a kid growing up in Saginaw, Michigan, in the US. He had spent the day slumped in an easy chair, staring at his phone, totally absorbed in an online urban myth. Johri knew it wasn't real, it couldn't be. And yet, he was powerless to get it out of his mind.

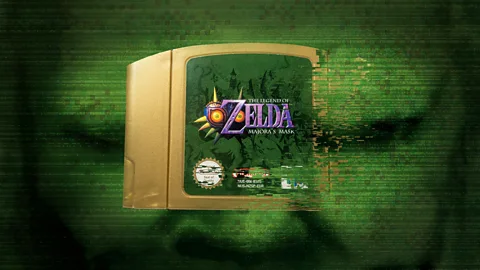

He had found a trail of old forum posts supposedly written by a college student. The student, who used the online pseudonym Jadusable, had bought a strange copy of a Nintendo 64 video game at a yard sale. It was The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask, a notoriously dark instalment in the Zelda franchise, released 25 years ago this week on 27 April 2000.

Majora's Mask is full of unnerving discussions about death, denial, fear, regret – and a looming apocalypse. But something was off about the cartridge Jadusable found. It had no label, just "Majora" scribbled on the plastic in marker. And something was seriously wrong with it.

Jadusable wrote that the game's familiar graphics were strange and distorted. Music played backwards in a spine-chilling loop. Worst of all, he was plagued by a terrifying statue of the main character, Link, with a petrified grimace on its face. It kept appearing in the game out of nowhere – like a digital ghost. On YouTube, Jadusable posted video evidence of everything he had described. This game cartridge, it seemed, was haunted – inhabited by the spirit of its former owner, a child named Ben who had drowned in a tragic accident. Johri pored over every detail, rapt with morbid curiosity.

As the story unfolded through roughly 11,000-words of forum entries posted over the course of weeks, Jadusable described a haunting that soon extended beyond the game to other areas of his life. Eventually, after a series of increasingly disturbing experiences, the forum posts ceased, and Jadusable was never heard from again. This urban legend burst onto the web in 2010, traumatising a generation of young internet users. It became known as "Ben Drowned".

Ben Drowned left an indelible mark on the web and continues to spawn art and fan fiction long after it emerged. Though lesser-known outside gaming circles, the story and its accompanying videos racked up millions of views and have inspired other narratives in a similar vein.

At its core, Ben Drowned is a story about a ghost in a machine – one that speaks to our deepest fears about new technology. But it's more than an effective urban legend. Ben Drowned is a myth born from a medium that shaped a generation. In an era when video games were still often seen as a frivolous pastime for children, Ben Drowned was early proof that society's relationship with video games goes beyond childhood nostalgia, tapping into our deepest emotions – and maybe even our souls.

By the time Johri stumbled on Ben Drowned in around 2015, it was already widely acknowledged as fiction. But that didn't matter. That night, on Christmas Eve, as Johri lay in bed wrestling with insomnia, he could see in his mind's eye that creepy statue's grimace projected onto the faces of his family members. Rumour had it that Ben, the ghost from the corrupted Majora's Mask cartridge, had gone on to torment other people besides Jadusable. That's what the adolescent Johri couldn't shake, however irrational it seemed. The idea that Ben's evil presence might be out there. That it could spread.

Nintendo/ Alex Hall

Nintendo/ Alex HallYears earlier, in September 2010, a real-life college student called Alex Hall hit "publish" on a forum post that would change his life forever. Hall had just started his second year at Saint Louis University in Missouri, US. He wasn't a fan of college. Here was his first taste of freedom as a so-called adult, and yet there were still all these classes to attend. He dreamt of becoming a famous author.

At the time, content called "copypastas" had become popular on forums such as 4chan and Something Awful. The term refers to the practice of copying and pasting blocks of text online, an early means of going viral – if such text proved popular enough to be shared widely. Ben Drowned is a canonical entry in an influential subgenre of copypasta called "creepypasta" – horror stories whose origins often become obscured as they spread across the web, thus adding to the mystery. Slender Man, a legend that was eventually turned into a big budget movie, is probably the most famous example.

By 2010, creepypastas had become extremely popular. But few of these stories concerned video games – despite the significance of games as cultural artefacts by that point. There were some examples, though, such as Polybius – a story that spread online in the early 2000s about mythical arcade game said to be part of a US government conspiracy.

Hall decided that the internet was missing something: an in-depth, video game-themed creepypasta. Gradually, his idea began to form: a haunted cartridge, a series of hoax-like forum posts, a narrator targeted by the evil entity within the game, and videos to back up these claims.

Hall knew how to make such videos using software to mod (modify) a game. He chose to use that software on Majora's Mask, Hall's favourite at the time. "That game, to me, felt like the most alive video game that I had ever played, really," he says. Characters talk at length about their grief, or express denial about their impending doom, even while the moon, which is on a collision course with the world, edges closer and closer overhead. "They have hopes and dreams," adds Hall.

The tale Hall came up with developed and amplified the grim mood of Majora's Mask, using the game as a springboard for a folk story about a troubled gamer. Hall's narrative leans on ominous lines of dialogue from the game. Most notably: "You shouldn't have done that."

The idea of a haunted Nintendo 64 cartridge came in part from Hall's own experience of trawling through yard sales for video games. He once found a copy of Star Wars Episode I: Racer, based on the pod-racing sequence from that film. "I was so bad at that game," recalls Hall. But the copy he found had a complete save file on it from the previous owner, meaning he could play as all the racers without having to unlock them first. This planted the seed that old game cartridges sometimes harboured surprises.

"A big part of gamer culture has always been about finding the secrets in different games," says John Sanders, assistant professor of English who studies media and literature at Appalachian State University in North Carolina, US. But while gamers seek to master the games they play, Ben Drowned is about a nightmare opposite scenario – this is a game that will master you.

Sanders points out that people have long told stories about corrupted or haunted media. The possessed game cartridge is just the latest in a line that includes ghostly radio broadcasts, cursed videotapes and demonic books. In Ben Drowned, Hall dangled the possibility that Ben might be able to haunt the reader too, via their computer. Another age-old ghost story trope: you're next.

After months of toil, Hall finally published his creation. A few days later, he woke up and logged on, bleary-eyed, to his YouTube channel. The first video he'd posted for the story had jumped up to nearly 2,000 views. Hall had never had such a response online before, and the view counter just kept ticking upwards. He picked up the phone and called his father. "Dad," Hall croaked, "I think I've done something here."

Nintendo/ Alex Hall

Nintendo/ Alex Hall"I actually remember reading it in my dorm room in college and sending it to some of my friends," says Alexander Zawacki, a digital humanities lecturer at the University of Göttingen, in Germany, who describes the thrill of discovering creepypastas through links shared on internet forums. Readers felt as though they were "getting into something a little bit secret", he adds.

Zawacki is one of a few researchers who have published academic papers about Ben Drowned. It is a classic example of a spooky story that employs childhood nostalgia, he says – like horror films peppered with dolls, clowns and little children. "They feel like relics of the past that come back to haunt you," says Zawacki.

Ben Drowned is a story that proves video games can be just as evocative.

That's significant, says Sanders. As video games matured, gaining more sophisticated graphics, complex characters and intricate storylines, they have given rise to entire subcultures – ardent gamers who trade knowledge about lore, cheat codes or hidden loot. They spend many hours exploring the digital worlds in the games they adore and sharing tales about the things they've seen that most people wouldn't believe.

Gamers' obsessions were leading to a "boiling point", adds Sanders, where a story like Ben Drowned had the chance of achieving real success.

Sanders also argues that Ben Drowned didn't just creep people out, it quite likely influenced later examples of urban legends about video games including Herobrine, a creepy, white-eyed character that supposedly appeared in Minecraft (but never actually did) and "PBBV", an evil spirit said to inhabit the virtual reality world of the game Gorilla Tag.

The creator of YouTube horror series Petscop, about a fictitious PlayStation One game that turns increasingly dark as the protagonist plays it, says he drew inspiration from Ben Drowned, among other sources.

Ben Drowned, which was first and foremost a text-based narrative complemented by video content, might seem anachronistic today. Zawacki says it's now more common to find stories like this presented in video-only formats.

Gaming writer and podcaster Marn Silverman, argues that while the delivery of Ben Drowned was "of its time", the story appears to have influenced a raft of video games built around the concept that they are possessed in one way or another – such as No Players Online, a supposedly haunted first-person shooter.

It's not surprising that a lot of these stories and games play on the nostalgia theme, says Emily Crawford, a digital media specialist in Washington DC who wrote about Ben Drowned while studying film and electronic media in graduate school. Games of the Nintendo 64 era, with their jagged, somewhat primitive 3D graphics, are especially good fodder for 21st Century ghost stories.

"The clunkier early technology left a lot more room for things to go wrong," Crawford says.

Technologies that are fallible have long given rise to anxiety and alarm. Ben Drowned is "an articulation of the fears of the internet age", says Sanders. "Viruses, corruption, the blurring of the boundary between me at the computer and the computer itself."

Ben's desperation to haunt someone, and to spread to other people's computers via the internet, is a kind of demonic "virality", adds Sanders. It fits existing worries about the web and what we might find there, giving the concept an unsettling plausibility.

Alamy

AlamyFor many, experiences with Ben Drowned as a child were formative. Charlie Duke, a college student in the US, was around eight when he first heard about the story. He found a video about Ben Drowned and that, a mere summary of the original creepypasta, was enough to chill him to the bone.

"I immediately closed the video," he recalls. "It got so stuck in my mind, it gave me anxiety for a long time." He even deleted a version of Majora's Mask he had on his computer, just to be safe. Duke says the ghost story played a significant role in debilitating anxiety attacks he suffered in the following years. He'd freeze up, hyperventilate and go completely pale. "It was always looking for a trigger and Ben Drowned happened to be one of those triggers, or even the main one at the time."

Saarthak Johri was also long-troubled by the story. The unnerving statue in the story that seemingly represented Ben's ghost, and the idea that he or his family members could be petrified in a similar way "freaked me out so much", he says.

Hall is aware that, for some people, Ben Drowned felt a little too real. "That stuff sucks," he says, adding that accounts like Duke's have made him feel a little guilty at times. "I want to tell people a story, I don't actually want to cause trauma."

Despite the unpleasant experiences that Johri and Duke say they had after reading Ben Drowned, both have positive things to say about it today. "It was kind of the first thing that connected me to other people in my middle school," says Johri. "You have litmus tests for how online or digital people might be and knowing about these creepypastas is one of them."

Duke says that Majora's Mask is one of his favourite games of all time. He has revisited Ben Drowned in the years since his first brush with the story and he notes that therapy has helped him to better understand and control his anxiety. "It allowed me to look at myself in ways I don't think a lot of people my age [did]," Duke says. "I don't know if would thank Ben Drowned for that, but it definitely played a part."

For Hall, writing an internet ghost story has led to other ventures including a new YouTube series he plans to release later this year called Dead Save, featuring alternate versions of classic video games. As with Ben Drowned, he'll use modding tools to edit those original games and bring to life urban myths about them that have circled online. He also says he would love to release a playable version of the haunted Majora's Mask cartridge one day.

But, reflecting on Ben Drowned 15 years after its original publication, there's something else to consider. While ghost stories about technology and video games remain popular, Sanders points out that we are all, these days, very used to the idea that there could be some malevolent actor trying to control our computer or harm us through our devices. Whether that's an email scam, social media bots, ransomware or people targeting us with disinformation or abusive content.

The threat lurking within technology isn't demonic, it's us. The "fantastic" supernaturalism of Ben Drowned seems almost quaint in comparison.

"Now we're just like, 'Oh yeah, it's out there, there are Bens out there waiting to happen, waiting to control our computers'," says Sanders. "We just don't think they're fantastic anymore."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.